This project was born during a train trip in France three years ago. I was giving a series of talks with Leila, a Palestinian refugee from al-Farradiyya (on whose land kibbutz Farod was established) who lives in Lebanon, at the invitation of a number of European organizations. After a few days, and a few hundred kilometers, we tried to think how we could do something together, despite (or because of) the fence and the border that separate us since the 1948 war. It seemed important to us that Palestinians who were expelled to Lebanon, together with Israelis, challenge the border between them by an act that will return Palestinians' presence to the place forbidden them since the Nakba.

We chose the village of al-Ras al- Ahmar, in the Galilee, none of whose residents succeeded in remaining in Israel as refugees. Almost all of them have been living since their village was captured in the refugee camp of Ein-el-Hilwe, next to the city of Sidon. The goal of the project was to bring those refugees' memories into Israeli territory, and in particular to the land of the village itself, on which moshav Kerem ben Zimra was established in 1949.

Activists from Leila's organization collected video testimonies from the village's refugees, and sent them to Zochrot. The idea was to turn them into a short film, with a Hebrew translation, and to show it to Israelis in Kerem ben Zimra and elsewhere. Ranin Jereis from Zochrot took additional photographs in the moshav and created a film that included the refugees' testimonies as well as pictures of the village today.

What the exhibition presents isn't what I've just described. The photographs in the exhibition are the outcome of an idea developed by Thierry Barsillon, a French photographer who works with one of the organizations supporting the project and who travels frequently to Lebanon and to Israel.

Erecting photographs amid the ruins of al-Ras al-Ahmar

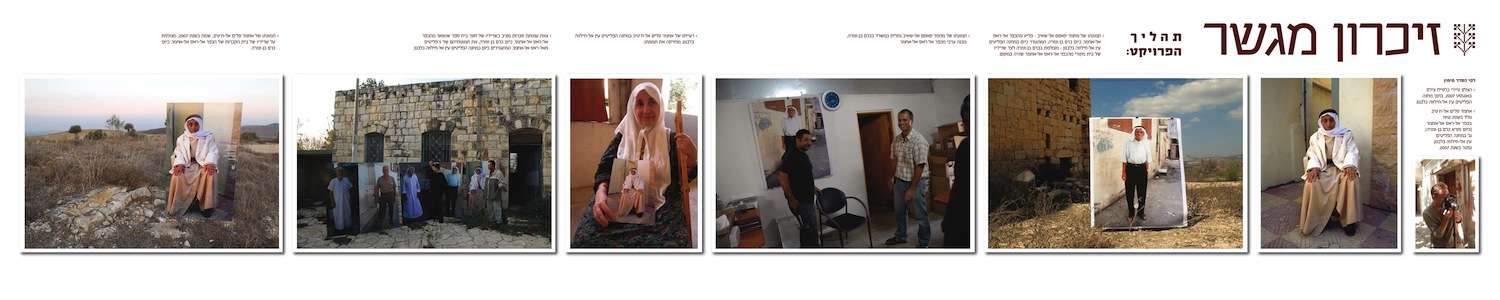

Thierry's idea was simple: to photograph the refugees from al- Ras al-Ahmar in their homes in Ein el-Hilwe, bring the photos to Israel, enlarge them to life-size, print them, and set them up amid the ruins of their village. At first I recoiled from the idea. It's hard for me to explain why. Something having to do with the bodily presence of the refugees who were uprooted and then returned anew to the place "where they belonged" but who are now so far away from it...

We tried it out. We made a lifesize enlargement of Muhammad Qassim al-Shaib's picture and took it to Kerem ben Zimra. We stood it next to a two-story Arab house from al-Ras al-Ahmar. He had returned to his "place", with Lebanon in the background, not so far from where he'd lived since being expelled. No more than a few minutes had passed before the moshav security chief appeared. He asked what we were going, and we explained the project to him. He was very interested in the refugee in the photograph, his name, his desire to return home. He told us that, as a child, he grew up in that two-story house, which belonged then to his grandmother.

He led us to another Arab house that serves as an office of an irrigation company. A fascinating conversation developed with two members of the moshav who worked there. Right of return – how is that possible? And if not – how will there be peace? Half an hour later they asked us to put the refugee's photograph on the office wall. We offered to return and organize a broader activity for additional moshav members. They hesitated, but didn't refuse outright. Thierry, who came with us to the moshav, took some photos for his next trip to Lebanon. We wondered how the refugees would feel about this activity. It turned out that they were very moved to see the photo of the refugee standing amid the remains of their village. Activists of the Lebanese organization, our "partner" in the project, had more reservations about cooperating with Israelis.

Encouraged by the refugees' response, we printed five lifesize enlargements, took them to the remains of the village and set them up next to the same building, and near the village school they had attended. The most moving photograph, for me, is that of Ahmad Salim al-Hatib in the remains of his village's cemetery. He died a few months before we placed his photograph in the cemetery in which he must have dreamed of being buried. If, as Barthes teaches us, photography is the cultural site of death, the photo of the still-living-but-already-dead refugee, next to his "grave", is an excellent example.

A series of gazes

The simple act of photographing the refugee in Lebanon, printing the photograph in Israel and positioning it next to the remains of his village creates a fragmented series of gazes:

Thierry looks at the subjects of his photographs and documents the moment they are looking into his camera.

We here, in Tel Aviv, look at the photographs and hear the stories of the refugees on video.

The life-size enlargements set up amid the remains of the village: near the school, next to the house that was left, and in the destroyed cemetery. Activists from Zochrot and additional moshav members look at them there, full-bodied yet two-dimensional, once again present in the place from which they were uprooted six decades earlier.

The refugees in the Lebanese refugee camp look at photographs of themselves placed by Israelis amid the ruins of their village; The photographs sit in Zochrot's offices, drawing the amazed gaze of everyone who comes in.

The life-size photographs, along with the photographs documenting the project as a whole, are set up on Rothschild Boulevard in Tel Aviv as part of an event commemorating the sixtieth anniversary of the decision to partition Palestine. Hundreds of people meet the refugees' gaze, and return it. Sometimes frightened, sometimes surprised, and sometimes like Neta Ahituv (in the photograph).

I look at her looking at Muhammad Qassim al-Shaib, the refugee, here in the exhibition, and think about the possibility of using photography to create a civil nation, as Ariela Azulay proposes.[1] Photography bridges time and space, the living and the dead, and allows us to envisage a civil nation. In this simulative civil nation uprooted Palestinian refugees, settlers living on their lands, partners of these settlers and those who carry on their work look at one another. This civil nation may demand the rehabilitation or the establishment of citizenship. Of the Nakba's victims as well as of those who caused it. The actual return of stateless Palestinian refugees to their country, to live together with Israelis, is what we dreamed about during that train trip, and that's what I see in these photographs.

Eitan Bronstein

Tel Aviv

June, 2008

זיכרון מגשר, תהליך הפרוייקט