15.9.2013. 25 people attended.

Speakers: Aiob abu Madigam, Yoav Gross, Eduardo Soteras Khalil and Dr. Ruthie Ginzburg

Eitan Bronstein Aparicio:

Ayoub’s exhibit of photographs, especially those documenting the first demolition of Araqib, led us to organize a discussion of “activist photography” – photography that consciously takes part in a political struggle, intervenes when rights are violated, etc. Activist photography has existed almost since photography began. This evening we’ll look at political photography from a number of perspectives. Photographs vary in how consciously political they are, as we’ll see in the projects to be presented here.

Aiob will begin; his photographs are on exhibit here. He’s a member of the community he’s documenting, so there’s almost no gulf between him as a photographer and the subjects of his photographs.

Aiob abu Madigam:

I studied Interactive Communication at Sapir College. From there I continued to photography, and decided to try it. I live in the Negev and am part of everything that happens there.

This exhibit had its origins eight months ago in honor of a Belgian group which conducted a bicycle ride in the Negev to support us. A photographer “one of them,” is part of the community, engaged in documenting it. I began photographing four years ago, which surprised many people in my community because photography as an art form was almost unknown there. People believe that the purpose of photography is to earn a living – at weddings, etc.

Documenting al-Araqib was special for me. I was 20, “a kid,” part of what I was documenting, the destruction of an entire village, 150 women and children. I was torn between photography and fear of those carrying out the demolition. Moreover, photography is a sensitive issue for Bedouins, particularly photographing women and girls. After gaining some experience, and because I’m part of the local community, I’ve been allowed to photograph whatever I wish. I’m also aware of the limits, so no one has ever complained about my photographs. People know me, understand that my photographs are taken on behalf of the Negev and those living there. I know the Negev’s culture and am aware of its inhibitions, but I’m not afraid to photograph women because I know what’s allowed and what’s forbidden. I also have family in Araqib; Sheikh Siah is a relative of mine.

Eitan:

What actually happened during the first demolition? How did you feel when some of the Bedouins who were evicted, often violently, were your relatives? What’s your status? On the one hand, you’re a photographer; on the other, they’re family.

Aiob:

They called me that day from al-Araqib to come take photographs. My parents didn’t let me go because they were afraid of what might happen to me. I called my older brother to come talk to my father, to convince him. He succeeded, and I went. I thought it wouldn’t take long, two or three hours at most. We sat with Sheikh Siach; activists were also there. They tried to delay the demolition, called the duty judge, but it didn’t help. Toward morning security forces blocked the Shoket junction, joined by a helicopter. They approached us; at that moment I didn’t know whether I would just take pictures or join them. Children were beaten, women also. I won’t forget the moment I saw the line of police. Am I allowed to come closer because I’m a photographer, or forbidden because I’m part of the population? I wasn’t wearing an ID. There was a very large force – it was said there were 1200 police and soldiers. And also bulldozers and other vehicles.

Kobi…Where’s Kobi? Here, in this photo [standing next to it, choked with emotion; there’s an oppressive silence. Someone brings him a glass of water]. He was in charge of the demolition. He stood with a microphone and said, “Either you leave peacefully or we’ll use force.” Kobi…he’s someone I can’t forget.

I was also hit, and asked myself whether I could respond? Should I keep photographing? If they arrest me I won’t be able to continue documenting what was going on. I had to take those pictures in order to show what was happening. To present my perspective, what I see, so that others will see what’s happening. Many people don’t know what’s happening there, many Jews, and a few of us also.

They first remove the men from the buildings, then the women. Here you see a woman holding her baby in one hand and her daughter in the other. You can also see activists who were beaten.

Eitan:

Where are you when you’re taking these photos?

Aiob:

I raise the camera high and take pictures. They actually made the photographers leave, but from time to time I returned for a minute to take pictures and left immediately. They brought a truck to remove the rubble and conceal the destruction, to show there’s no village there. Neither ruins nor buildings remained.

Why don’t the photos show ATV’s and bulldozers? I prefer to show people. I want someone looking at the pictures to see what happened to the people, not to the buildings. I think they’re more powerful photos than shots of a bulldozer demolishing a house. Seeing people in the photos may cause viewers to ask whether they themselves can do anything.

Question:

Since then you’ve been present at many demolitions. Have you changed the way you photograph? Do you think like a photographer? Can I do something new, stand back from what’s happening, think about how to transmit the feeling, be innovative in a photographic sense?

Aiob:

The first demolition was a frightening experience. Later I was no longer afraid, I know I’m a photographer, I have a right to photograph, I can’t be prevented from doing so. I began thinking like a photographer, insulated from feelings, from my family.

I’m a photographer who’s not connected to any particular web site or newspaper. That’s a problem because I don’t have a credential showing that I’m from a paper or web site. That’s why I’m not able to photograph everywhere.

Eitan:

Yoav Gross, from “B’Tselem,” will discuss “Armed With Cameras”, the project they’re conducting on the West Bank to document human rights violations. They give video cameras to Palestinians who then document various incidents. Some of the films are distributed to the media in Israel and abroad.

Yoav Gross:

I want to begin by saying something about Ayoub Abu Madigam’s exhibit – very often photos taken by activists are very similar to one another. But this exhibit is extremely varied, and that’s very impressive.

The “Armed With Cameras” project began six years ago because we needed evidence from the field. We faced a serious problem: accounts by Palestinians were not believed by courts and the Israeli public. So we had to demonstrate their veracity by footage supporting their testimony. We began distributing cameras to Palestinians in Hebron and, later, elsewhere. Over time, we received very powerful, blunt footages and very strong evidences that resonated in the media in Israel, abroad and in Palestine.

Video footage of human rights violations over the past two years was unequivocal and undeniable. The most well known were of the soldier who violated orders by shooting a bound Palestinian, and four masked settlers clubbing a Palestinian shepherd. That was the first time I’d seen masked settlers. Another was the sharmuta [whore] video in Hebron. The project developed since then until the incident of the five-year-old boy in Hebron who was arrested and put into a jeep. What’s interesting is that women filmed all those particular videos. That wasn’t intentional…many others were filmed by men.

One question that arises is what to do when the video doesn’t end the occupation? It doesn’t solve the problem. What do you do when the occupation not only continues, but keeps growing more complex, filthier? There’s a feeling that the violation of the rights of people under occupation is something elusive, abstract, hard to photograph and publicize. That’s something we tried to deal with in the video you’ll see shortly.

Another question is how an Israeli organization tells the story of the occupation, which is a Palestinian story, and particularly the story of the victim of the violations who’s Palestinian?

The video shot by Bilal Tamimi from the village of Nebi Salah was made in 2011. Bilal is a very skilled and experienced photographer. He’s from the village, active in demonstrations, although this video wasn’t shot during a demonstration. The video shows the essence of the occupation as it really is, the Palestinian experience of the occupation. No Israeli could have filmed that video. It’s complex. There’s “evil,” but the soldiers aren’t themselves “evil.” They seem to know exactly what they’re doing, or they’re strangely aware, aware of the camera, trying to be polite. But above all you see how soldiers enter a family’s home in the middle of the night, wake them up just to photograph the children.

Question:

Can you tell us a little more about the project?

Yoav:

We distribute video cameras and cinematographers run workshops every week or two. We’ve distributed about 400 cameras; about 150-180 people are actively photographing. B’Tselem field staff, who run the project, decide who’ll get cameras. They’re in contact with volunteers, collect material, run the training.

Sometimes we’re afraid that the army or the police will take our films and use them to look for evidence against Palestinians. There were many cases in which Palestinians were already released in the field because of the film. Showing the film to the soldiers convinced them to release detainees who hadn’t done anything.

Our archive contains thousands of hours of footage showing clear violations of human rights. It’s open to anyone who wants to use the footage, under certain conditions, in an appropriate human rights context and with the photographers’ approval. The archive is accessible only at our offices. We’ve uploaded some of the footage to the internet.

Question:

Has the presence of cameras made a difference in the behavior of the occupiers?

Yoav:

In some cases, definitely – in the behavior of the security forces and in the degree of settler violence. But not with respect to the fundamental issues, such as the theft of land. This project has led to a significant change in the way Palestinians feel about the law and the soldiers. The fact that photography has become so widespread – not just our project – affects everyone. Places that had formerly been unknown in Israel are now accessible to newsrooms.

Eitan:

Thank you, Yoav. I also want to mention the wonderful short film, “Susya,” which Yoav made with Danny Rosenberg.

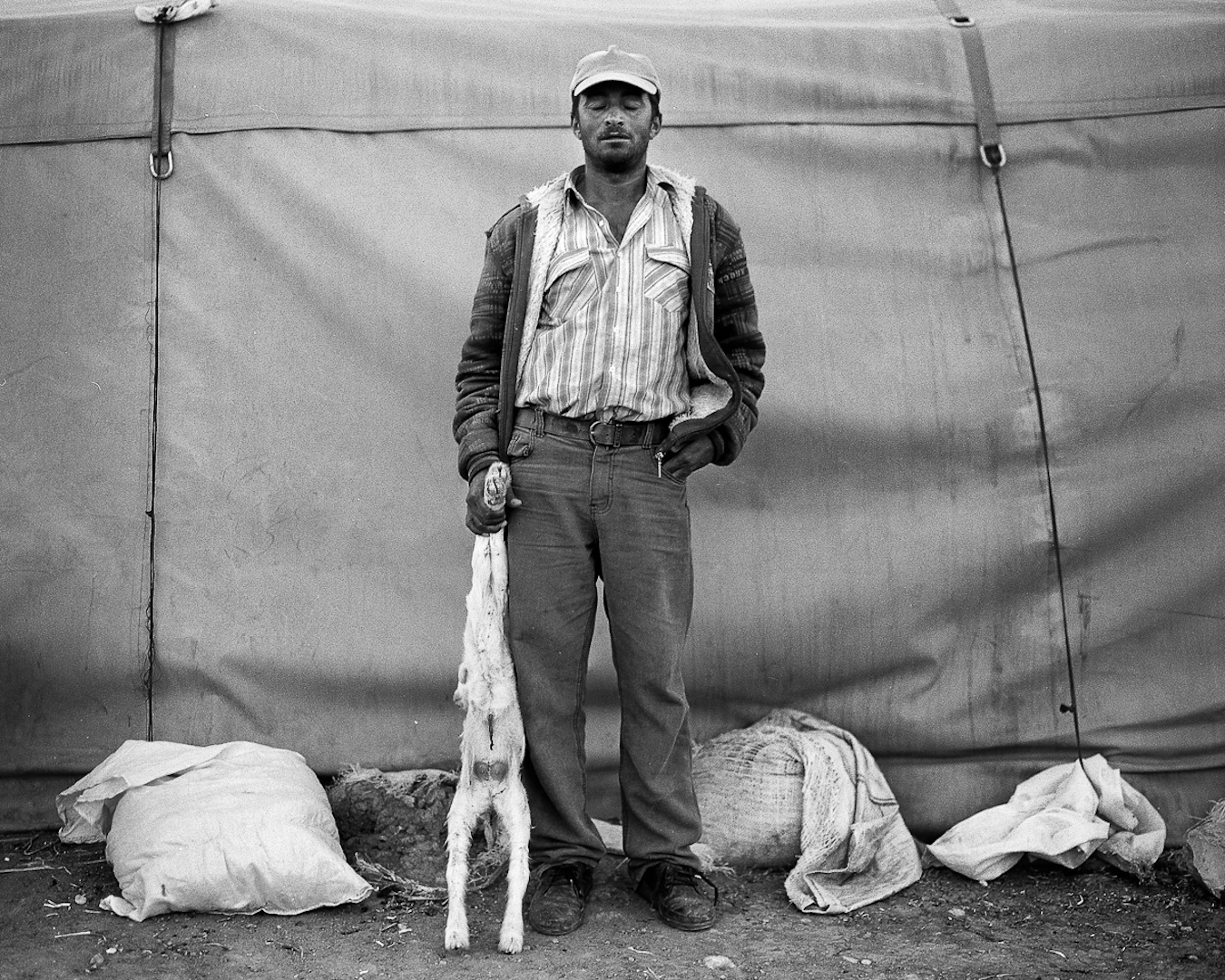

Let’s now turn to Eduardo Sotras Khalil. I don’t think many in our audience are familiar with what you’re doing in the southern Hebron hills, and I’m very glad you’re here this evening. When I first saw your photos I thought they were astonishing, that you’re extremely talented – but then I realized there was a problem. You photograph people – you don’t show obvious violations of human rights but a community living under the threat of expulsion – and your photos are beautiful! Isn’t there a danger that your photos will be seen only as beautiful, as documenting an exotic way of life in caves and godforsaken locations?

Eduardo:

I’ve been photographing life in the southern Hebron hills for the past two years. My language is the language of photography. I agree with what Eitan said about the beauty of the photographs. What’s happening today with Facebook is very interesting, when someone uploads such a lovely photograph of a corpse from the war in Syria, and people “Like” it. I think it’s also problematical to believe that the photo is the truth, that it’s innocent.

Sometimes there are too many photographs of conflicts. Photographers working for the major news organization are based in Jerusalem and don’t stop documenting what’s going on.

I taught press photography at Al Najah University. I’ve recently noticed that Palestinians have begun photographing in the same way as those coming from outside. Yes, it’s important to photograph demonstrations, but it’s also important to tell other stories. When I began photographing I was involved with ActiveStills, but today I work differently; I’m interested in developing a photographic language, using it to portray what life is like. That was a very important decision for me. So I almost never photograph soldiers; it was important for me to put them aside. Nor do I photograph settlers and rubble, although there’s a great deal of it. You can find that elsewhere.

My photographs try to say something intimate about people. I decided that photography would be part of my life, so I erased the boundary between the two. I live most of the time in the southern Hebron hills, so there’s no boundary between my life and the lives of those who appear in my photographs. They’re the major portion of my social life; I’m part of where I photograph.

You can call it politics; perhaps it’s art. For me it’s just life. I’d like to believe photography can create a better world. It can show people things they don’t usually see, build a bridge between people. It’s important to me that every picture portrays love. If I approach a photograph as ethnography or politics it’s ruined. For a year I’ve lived in a tent in Khirbet a-Tuba, and sometimes in my girlfriend’s home in Neve Shalom.

Dr. Ruthie Ginzburg:

I’m a member of Zochrot’s Board of Directors. I wrote my doctoral dissertation on Israeli human rights organizations working in the territories occupied in 1967. I tried to look through their eyes, to understand their perspectives. What choices do they make? I focused primarily on Machsom Watch and B’Tselem.

I was interested in the cooperation between the organizations and the population, between amateurs and professionals. You could say the first world needs photos of the third world, and agencies provide them.

I call it “activist documentation,” though the two don’t necessarily go together. Photographing reality shouldn’t be connected to activism which implies involvement on behalf of change or preservation. Activist photography doesn’t intend to portray reality but to preserve or transform it. That’s how photography in the occupied territories transforms documentation into activism.

We saw Bilal Tamimi in B’Tselem’s video. His filming constitutes activism in reverse. Soldiers enter his home in the middle of the night while his children are sleeping to photograph them. Instead of attacking them he picks up a camera and documents what’s happening. Instead of arguing, he films; that’s his activism. He then follows them to the next house they enter.

With the invention of photography it became a tool for documentation, a tool that was believable. The events of the Arab Spring were documented primarily by civilians using social networks which allowed them to upload images to the web and, of course, by using cell phone cameras.

We see civil society organizations assisting people to use photography like B’Tselem does, providing cameras, instruction, allowing them to photograph daily life, difficulties, denial of rights and in this way to defend the community.

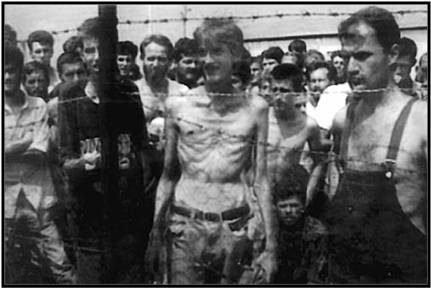

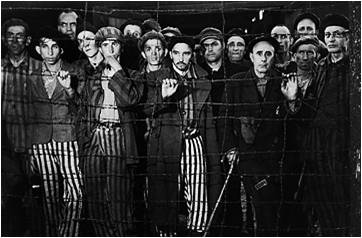

An interesting question is whether the subjects of the photographs benefit from having their picture taken. There’s criticism of “photographing the other.”

Miki Kratzman and Boaz Arad gave disposal cameras to drug addicts, promising them NIS 50 in return for a full roll of pictures. They developed the photos and mounted an exhibit presented as art. That raises questions about the relationship between the person providing the cameras and the one taking the pictures.

הרס עראקיב יולי 2010 / Destrution of Araqib July 2010

דרום הר חברון / South Hebron

דרום הר חברון / South Hebron

דרום הר חברון / South Hebron

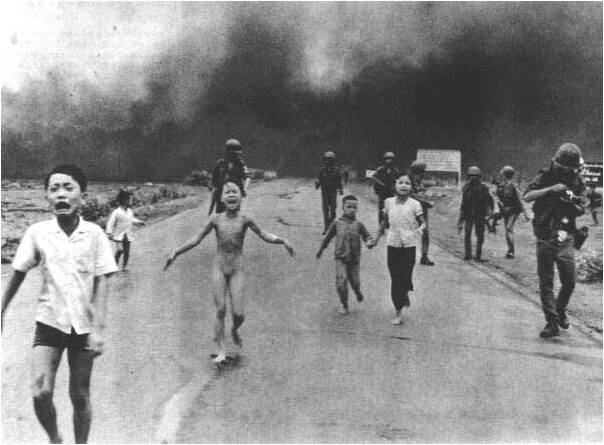

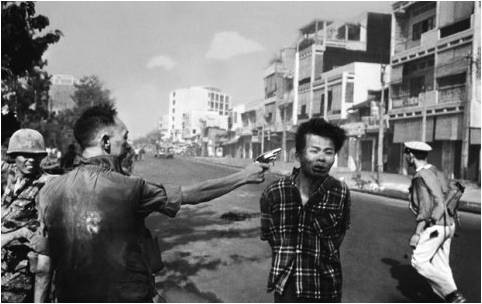

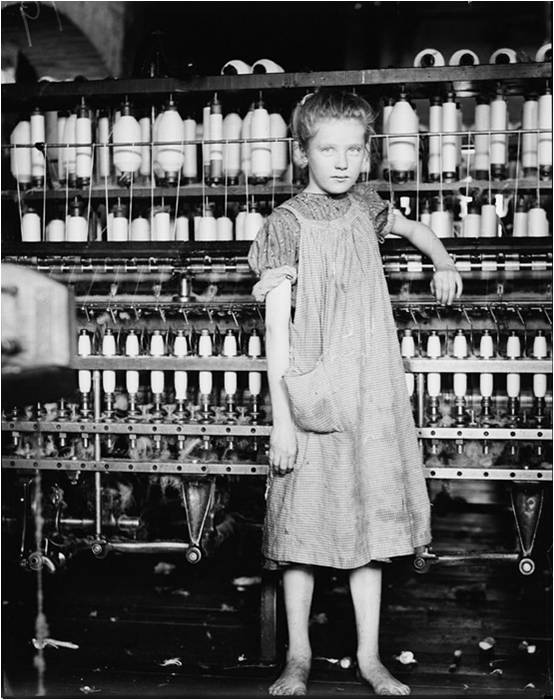

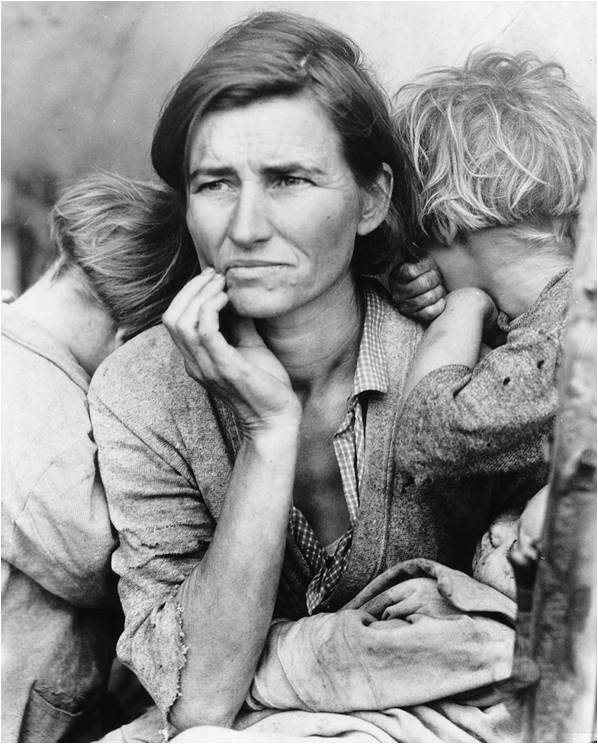

צילום תיעודי אקטיביסטי / Documentary and activism photography

צילום תיעודי אקטיביסטי / Documentary and activism photography

צילום תיעודי אקטיביסטי / Documentary and activism photography

צילום תיעודי אקטיביסטי / Documentary and activism photography

צילום תיעודי אקטיביסטי / Documentary and activism photography

צילום תיעודי אקטיביסטי / Documentary and activism photography

צילום תיעודי אקטיביסטי / Documentary and activism photography

צילום תיעודי אקטיביסטי / Documentary and activism photography

צילום תיעודי אקטיביסטי / Documentary and activism photography

צילום תיעודי אקטיביסטי / Documentary and activism photography

צילום תיעודי אקטיביסטי / Documentary and activism photography