I’m amazed that Dr. Yehiel Shabi sees the iNakba app that Zochrot will launch on Independence Eve as “proof of the refusal to accept Israel’s existence.” As one who founded Zochrot 13 years ago and deals with the Nakba every day I feel increasingly connected to this place, to its landscape, to its culture, a connection that strengthens and deepens the more I learn about the Nakba.

What Shabi says exemplifies Zionism’s approach, much less Israel’s, to the region in which it realized its colonialist project: the Jewish settlers aren’t interested in the actual history, geography, memory and language of this county. The Land of Israel is but a mythological realm. The settlers and conquerors of the country aren’t really interested in living here. They’re here as conquerors, and remain conquerors. That’s how pre-state Zionist immigration led to the uprooting of 62 Arab localities, followed by the destruction of an additional 678 Palestinian localities during the Nakba, continuing with the ongoing occupation that began in 1967.

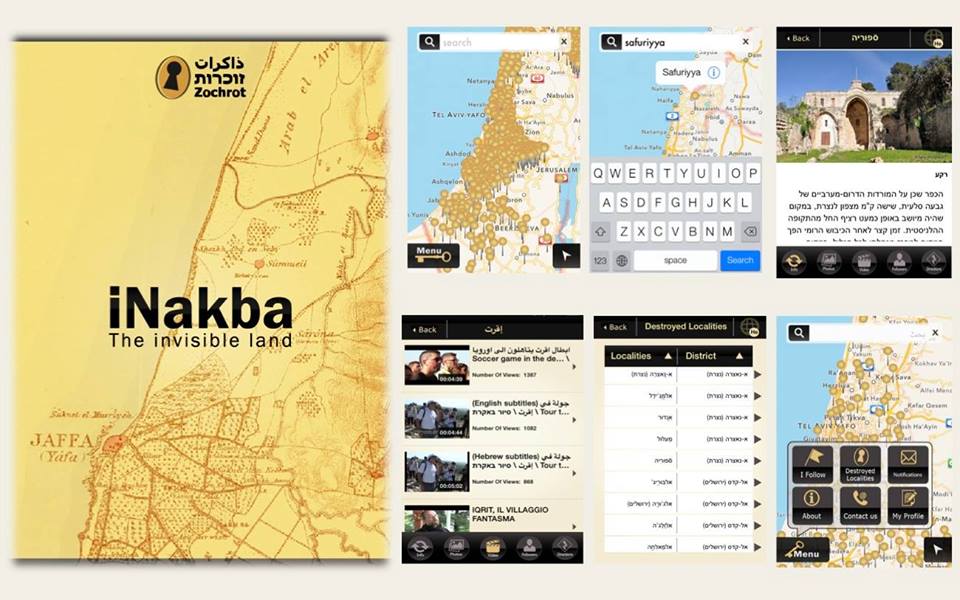

iNakba lets people learn about the Nakba, thereby connecting all who live here to the country’s actual history and geography, which belong also to Israeli Jews. They’re not simply, according to Shabi, an expression of “Palestinian aspirations.” In fact, the insistence on understanding the nakba as a purely Palestinian concern (as in the expression “Palestinian narrative”) serves to strengthen and deepen the separation which Zionism created between Jews and Arabs in the country from the beginning of Zionist immigration.

We at Zochrot learned from elderly Palestinian refugees the fascinating distinction they had already been aware of before 1948, one which should be taught in every Israeli school, between “Palestinian Jews” and “Zionist Jews.” The former lived as a minority among Arabs in Safed, Tiberias, Jerusalem, Haifa and elsewhere. They spoke the language of the country and were an integral part of it. The Zionist immigrants, on the other hand, separated themselves right from the start from the country’s Arab inhabitants. It’s sad to think that the Zionists were mainly interested in the country’s inhabitants from a military perspective. They learned Arabic primarily to gather intelligence (which is still true today); the Hagana’s Information Service was interested in Arab localities in order to create the village files that eventually were used to attack them.

Hasn’t the time come for Jews to learn about where they live in a very different way? We have to be taught in a manner that respects the land’s culture, that recognizes the terrible injustice that Zionism did to the Palestinians. That won’t push us out; on the contrary, it will allow us to be accepted here.

The map in Arabic Shabi includes in his article is another expression of the desire to separate Jews from Arabs. The Nakba map Zochrot published last year is in Hebrew and includes all the localities in the country that have been destroyed from the beginning of Zionist settlement until the 1967 war. These also include (in addition to those noted above) 22 Jewish localities destroyed in 1948 by military units of Arab countries – not by Palestinians living in the country. The map is an additional important tool to connect the country’s Jews to their region – the actual place, not the mythological one.

Shabi is correct to link the demolished Palestinian localities to the right of return of Palestinian refugees and their descendants. He compares it to other conflicts in which refugees were not granted the right of return but ignores the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, South Africa and other cases in which the right of return was included in peace agreements and even implemented as much as possible. That’s what should happen here, and soon. The Palestinian refugees’ right of return will be recognized and the return will occur while taking into consideration the new realities that have been created in the country since 1948.

I’m happy to conclude with the words Shabi used at the end of his article: iNakba allows you to learn about the country and see how the right of return can actually be implemented not only virtually, but actually.

Join our efforts to expose the truth

Join UsRelated Keywords

Resist the ongoing Nakba

Help us resist the ongoing Nakba

Donate NowJoin our efforts in exposing the truth about the ongoing Nakba and in promoting acknowledgement and responsibility for the injustices of the Nakba, support for the right of return and a commitment to building a just society for all in Palestine.