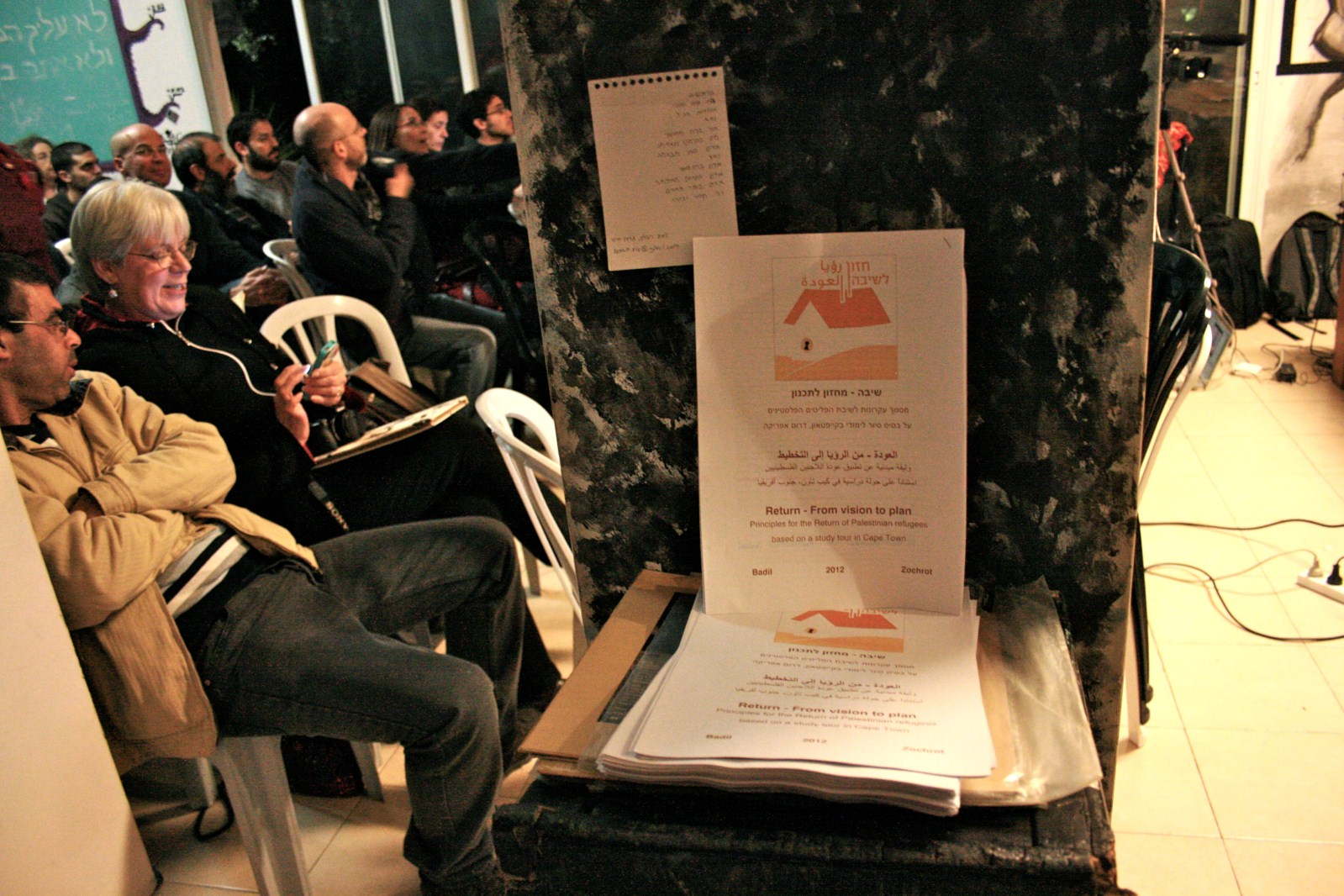

Beit Ha'am (The House of the People), 69 Rotshild St. Tel Aviv, 23.12.2012

Noa Levy reads the proclamation of return:

Recognizing the historic injustice committed in 1948 and afterwards, Hoping for a better, cooperative future,We, Jews who live here, in IsraelCall for the return of the Palestinian refugees to their homeland, which is also our homeland.

The return of the Palestinian refugees does not mean that others will be uprooted and destroyed. It is a shared vision of a just, egalitarian future that will be better for us all. Nor is the return only a dream or a hope, but a right recognized in UN Resolution 194.

The Capetown documents, which were prepared jointly by Jews and Palestinians, define the preconditions for the practical implementation of the return, based on the following principles:

1. Our shared land has enough room and sufficient resources to resettle and compensate those of its inhabitants who were exiled, without evicting anyone from their home.

2. The actual return will be preceded by a process of winning over all the communities affected. The process of healing past wounds will continue after the return begins, through ongoing community work.

3. After the return, the country will really and truly act according to principles of freedom, justice and peace. All its inhabitants will have equal rights. The country will ensure freedom of religion, education, conscience, language and culture and will protect the holy sites of all religions.

After the refugees were exiled from their land they kept faith with it in all their diasporas, never ceasing to pray and hope to return to their homeland. We entreat the Palestinian refugees in the refugee camps and everywhere else: Return! We will join you to build the land. Come home!

Yonatan Shapira is singing.

Liat Rosenberg, director of Zochrot:

This evening we are inaugurating in this community center, a symbolically important site, the document we call “Vision of Return,” a joint project of Zochrot and Badil, from Bethlehem. The document reviews Zochrot’s activities – it’s unique and groundbreaking. For years, Zochrot’s agenda has focused on the return of the Palestinian refugees. Zochrot’s approach was distinguished by the set of principles it formulated for planning the return in the context of possible alternative political arrangements. We did not choose Capetown, in South Africa, by accident – it’s a place that helps us understand the transition from an apartheid to a post-apartheid regime. I would like to thank the ten participants who travelled to South Africa and the other Zochrot acitivists.

Umar al-Ghubari:

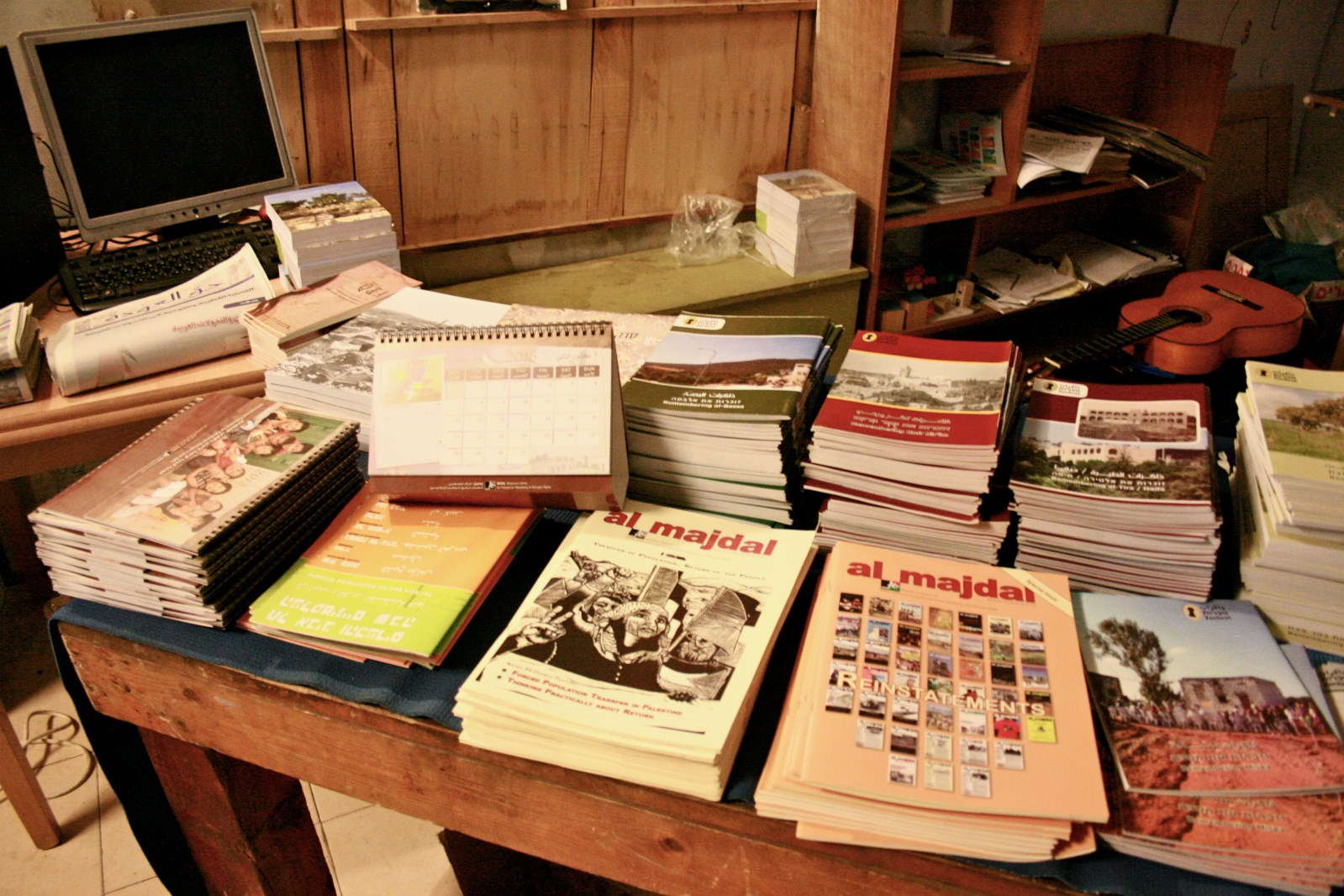

The document is available in Hebrew and English on Zochrot’s website; we hope it will soon appear in Arabic as well. We welcome discussion of the topics and ideas presented there and will be happy to receive written responses. We’ve invited three people to talk about the document: Dr. Manar Makhoul, a Palestinian citizen of Israel from Peki’in; Budur Hassan, a social activist and journalist; Eitan Bronstein Aparicio, one of the initiators of the document and a member of the South Africa group. We invited Eyal Megged, the writer, to respond; he agreed even though he doesn’t agree with the document. Unfortunately, an hour and a half ago we received an email in which he notified us that he would not appear. He wrote that it would be irresponsible for him to participate.

Zochrot’s approach to the right of return has undergone a number of changes over the years. Questions have been raised, including intra-Palestinian questions that hadn’t come up in the past. While there may be other groups which recognize the right of return, only Zochrot addresses its practical implications.

We begin with two principles: people will not be evicted from their homes; the right of all refugees and their descendants to return is guaranteed. What will the return to existing cities look like, compared to the return to areas still unpopulated? This is the first time that we and Palestinian refugees have presented various alternatives of return. Take the village of Sheikh Muwanis, for example, which was completely destroyed and where Tel Aviv University now stands: no one, including the refugees, calls for the demolition of the university. But neither do they relinquish their rights to the location and the property.

A second question: Will we dismantle the refugee camps to implement the return, or build new towns to which their inhabitants can move and preserve their community structure?

What will happen to the sites of the refugee camps? The technical answer is that they are UN areas and can be vacated. But that led to a serious discussion of the fact that the camp was a place where a meaningful community formed. People want to leave the camps behind, but the camps were part of the refugees’ experience.

What about those who had been wealthy, who owned property? Returning the rich to their private holdings will have the effect of maintaining the inequality between them and those who have no land to return to or whose land is now the site of a city. Will the formerly wealthy Palestinian be rich once more? It’s a question of social justice: is the issue one of “land,” or of “homeland”? The return won’t necessarily be to the same plot of land someone had owned in the past.

The document has three sections:1. Preparing the return2. Implementation – return, redress, compensation3. The vision of a new country

Manar Makhoul:

I wasn’t in Capetown nor involved in drafting the document. I want to focus on opening the document for public discussion. I’d like to present Badil’s approach in order to encourage discussion instead of giving a lecture. Badil was established in 1998. The name means “alternative” in Arabic. It was intended to provide an alternative to the peace process that excluded the refugees from the political conversation. We support the refugees’ right of return. Our view is that no political process can revoke rights. No agreement can revoke the Palestinians’ rights. In my personal opinion, Abu Mazen has no mandate to represent the refugees, because they didn’t vote for him. Such an agreement would be void, invalid.

The right of return is based on international law. Not on religious or national ideology, but on the legal rights of the Palestinian refugees according to international law.

Badil works along with Zochrot, whose goal is to expose the history of the ongoing nakba, to uncover and analyze how the refugees came into being and why they are still refugees. They attributed the problem to Zionist ideology, according to which it was necessary to establish a Jewish national home, inevitably at the expense of the Palestinians. No peace process that favors Jews at the expense of Palestinians can succeed because it doesn’t eliminate the root problem.

The Nakba and the creation of the refugees was not a single historical event that ended in 1949, but one that continues today – in the Galilee, in Jaffa, in the territories occupied in 1967. It changes form; under the veneer of legality it demolishes homes and limits the ability of people to move freely.

New alternative solutions to the conflict must be developed that don’t prefer one side over the other. I recommend that everyone read the document because it answers many questions, questions that I also had asked. The document tries to draw lessons from other historical situations. For example, the movement that led to the end of apartheid “stalled” at the moment of its success. The document plants some seeds of possible ideas that could lead to a sustainable solution to the problem of the refugees.

Salman Abu Sitta asked in his research whether return was even possible. That’s not only a moral solution; in my view, it’s the only idea that could succeed. Any peace agreement supported by the majority of the “Palestinian people” would in effect be an agreement with all those in the diaspora. Most of the destroyed Palestinian areas are available for resettlement. Most of the Jewish population lives in the Dan region.

Questions arise regarding the return: Where will they return to? How many will return?We believe that it is important at this moment to establish the right to return. It’s a simple equation: if a Jew has a right to return after 2000 years, a Palestinian has a right after 65 years. Second, the right is founded on international law. Third, it isn’t important how many return. The majority favors establishing the right, even though no one knows exactly how many will return. Just like Israel’s Law of Return which grants the right to every Jew, but not all of them move to Israel.

The document is also important to Badil in connection with internal Palestinian discussions on the right of return because it presents a solution for all Palestinians, including those living in Israel. Approximately 30% of Palestinians in Israel are internal refugees.

Umar:

An interesting aspect of the connection between Zochrot and B’dil is the dissemination of material we prepare jointly. Capetown isn’t the first example. We previously prepared a document in Belgrade when we investigated solutions in the Balkans. It took Badil a while to accept the idea that the material could be released publicly. They wanted to wait. The Capetown document, on the other hand, was published by B’dil even before we issued it.

Our work challenges, on the one hand, Israeli fears about the refugees’ return and, on the other hand, the Palestinian fantasy of returning to the lost paradise.

Eitan Bronstein Aparicio:

I believe there’s a fascinating and potentially creative contradiction between utopian thought about a future situation the timing of which is unknowable, and down-to-earth, practical thinking about the post-return utopia. It’s a frightening contradiction, so daunting it deters people from considering it, but I believe it’s the only way of imagining life here founded on reconciliation and peace. Current discourse fails almost completely to propose an Israeli political vision conceiving the possibility of peace between the sides. We’re talking about an attempt to imagine it. Imagination becomes an indispensable political tool in a hopeless situation.

I want to focus on a specific point in the document that in my opinion justified the entire process involved in its formulation. That point, which I believe is critical, was relegated to a footnote. We had an interesting argument in Capetown about the issue central to Israeli fears: “What if a Palestinian shows up wanting your home?” That is, what will we do if refugees want to return to their home but Jews are living there (or perhaps Palestinians)? I think it’s a little ridiculous, because Israelis move for various reasons, some related to the value of their property, as well as others, so why shouldn’t they move for a peace agreement? But let’s get to the point. Ariela Azoulay claims that Israel demolished 100,000 buildings since the nakba, so there aren’t many structures left in their original condition to which people can return. In Capetown we had a new idea regarding this fraught topic which sort of faded away in the Hebrew text.

The notion is to distinguish between ownership and habitation. In other words, the former owner won’t necessarily live there again. The idea is that if the home hadn’t undergone significant alterations, and the returning refugee wants it back, he’ll have the right to receive it. The current occupants will be appropriately compensated for the property they bought. Since most of the original refugees are no longer living, their rights pass to their heirs, but then the question arises of their rights versus those of the current occupants who’d purchased the property fairly and legally. Does the right of the Palestinian heir necessarily supersede that of the occupants who’d bought the house? I don’t think so. Jews have rights to those homes. Squatters also have rights …

In my view, the people currently living there will continue to do so, but legal title will pass to the refugees’ heirs. The current occupants will live there under an arrangement similar to key money. The idea led to many arguments, also among Palestinians, and the view I’m expressing is only my personal opinion. Separating ownership from use makes it possible to develop new, creative solutions.

To conclude – regarding Eyal Megged. He initially agreed enthusiastically to appear but backed out at the last minute. I think that’s an example of the Israeli fear of dealing with the sensitive issue of the return – they’ll return at our expense just as we came at their expense in 1948. We, of course, are trying to develop alternatives that don’t involve expulsion. It’s time to face this fear courageously and overcome it.

Budur Hassan:

I'd like to talk about 3 intra-Palestinian issues: The first question is about social justice – it’s very important that the document talks about it. Before 1948 it wasn't a perfect society, there were huge inequalities. Peasants, landlords, many conflicts even among Palestinians and we don't often talk about them. So do we return the property to its former owners, or do we regard it as a collective right? This is the right way - not just restorative justice but also redistributive justice. Personally I'd like it to live in a socialist society but I'm not the one who decides, and many will not agree with my vision for this country. But it's very important to respect first of all the right of all Palestinians to live in equality, not just ethnic/national but also social. It's also necessary to look at it from the gender point of view. Before 1948 property holders were mostly men, and inheritors were mostly men, so there's a disparity between what men and women are entitled to inherit.Another question: after 1948 there were people, Palestinians, who were more privileged and others who were less privileged, like the refugees in Lebanon. So what they will do in Palestine is an important question. How will they find work? Many of them don't have education. So, again - not just restorative but also distributive justice. We must discuss it now, not wait for the return. Regarding Palestinians who have already formed identities in the diaspora. In Syria many Palestinians had to flee because of the fighting, and they started dreaming about return to the camp, thinking of the camp as if it were their homeland. The same is true for people living in other refugee camps. So it's not just a romantic issue; a lot of healing work must be done among Palestinians. Also, it's a matter of choice; we won't make anyone return, they must be able to choose. It's important to give voice to the feelings and other identities that have been formed in the diaspora. The question of adapting to the situation here, with Palestinians already living here: I can understand the Jewish fears of reverse ethnic cleansing, etc., though can't empathize with them because they are grounded in racist motivations. But there are also the fears of Palestinians already living here. How will we manage to build a society without reconciliation among Palestinians themselves? The best solution is to increase the ties between Palestinians of 1948 and 1967 and Palestinian refugees. There is a need for grassroots initiatives in this context.

Umar:

A few years ago I met a kibbutznik on one of Zochrot’s tours who said, “You view me as a stranger in this land.” I replied, “I view you as someone who insists on remaining a stranger.” The desire of Israelis to be like Europeans preserves the supercilious attitude of Israeli Jews and perpetuates the conflict. This desire also perpetuates the gap between Jews and Arabs in the Middle East. The document we launch today can free Israelis from their racist identity.

Adaya (from the audience):

Umar, when you spoke about the Palestinian fantasy, that it was shattered, what were you referring to?

Umar:

When we meet with elderly Palestinians, we “destroy” the Palestine they imagine, the one that existed in 1948. I show them what the place looks like today.

Nitzan (from the audience):

I want to thank you for your courage and your ability to think about those things during these terrible times. I came this evening by chance, and am very glad I did. It may not be necessary to go to South Africa in order to find creative ideas; go back to the origins of the Zionist movement and look at today’s terrible, horrible reality. And to Budur: There was a great difference between Jews in Palestine and in the diaspora. And what you said, Manar, that there are refugees living here, and families that have been split – that’s truly terrible.

Manar:

You can see from my village, Peki’in, the stubborn insistence of Zionism to remain a stranger in the land. Why do all the Jewish kibbutzim and moshavim in the area continue to grow, and the fences surrounding them lengthen as well? It’s a colonial mentality; what’s happening on the West Bank is also happening in the Galilee. They still live in a settlers’ bubble, distinct from the surroundings, also architecturally. A Jewish locality is like a bubble that doesn’t merge with its surroundings.

And regarding Palestinian identity – Palestinian discourse in Israel has also advanced since 1948. Since the end of the 1980’s Palestinian discourse has begun referring back to the utopia of what Palestine had been, and that the Nakba was what Palestinians everywhere had in common. As if in reaction to the Oslo Agreement, we’re reminded that the problem didn’t begin in 1967 but in 1948. So identity is something that develops over time.

השקת מסמך חזון לשיבה / Launch of Capetown document

השקת מסמך חזון לשיבה / Launch of Capetown document

השקת מסמך חזון לשיבה / Launch of Capetown document

השקת מסמך חזון לשיבה / Launch of Capetown document

השקת מסמך חזון לשיבה / Launch of Capetown document

השקת מסמך חזון לשיבה / Launch of Capetown document

השקת מסמך חזון לשיבה / Launch of Capetown document