The exhibit is dedicated to the memory of Faisal al-Husseini

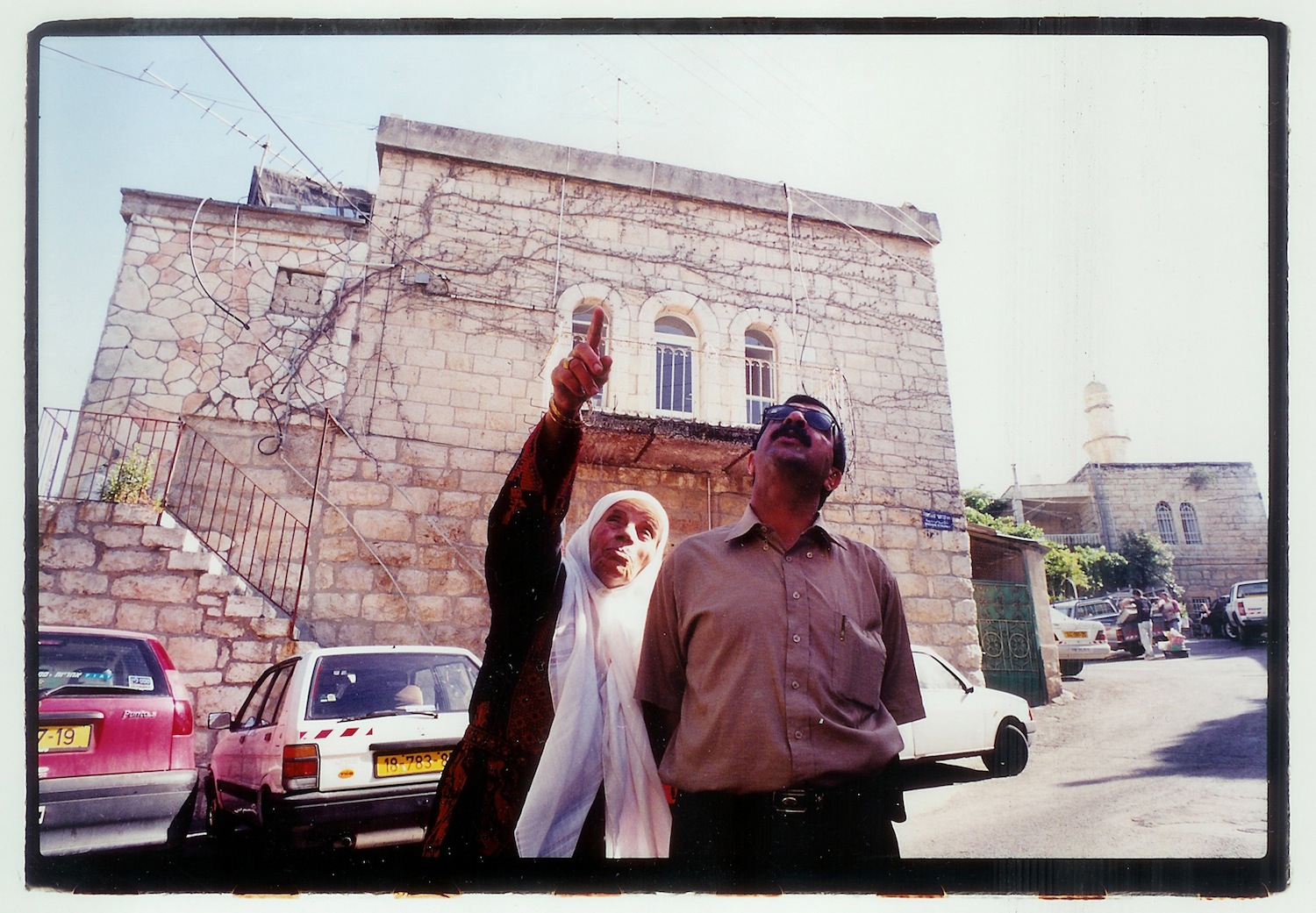

About ten years ago we came to Faisal al-Husseini with the idea of encouraging Palestinians who had become refugees from west Jerusalem – they themselves, or their parents – and who had lived in the city for generations, to talk about the Nakba. We asked him for help, and he willingly agreed: locating the buildings, identifying the families, collecting testimonies, building trust, everything.

We listened to the Nakba's refugees, photographed their homes on this side of the Green Line, and tried to capture the moment when they were parted from them. The help we received from the staff of the Orient House was what enabled us to retrieve the little we were able to recover from the depths of forgetting and denial, before Faisal al-Husseini died and his Orient House was captured and looted and sealed by Israel.

Sa'id Abu al-Nahas al-Mutasha'il, the unfortunate "pessoptimist," already told us once, with the help of Emile Habibi, who we fondly remember and who received the Israel Prize in literature: "I disappeared from sight, but didn't leave this site." And perhaps that's what he wanted to teach us, that between "disappearing from sight" and "the site we still inhabit" there are connections hidden from the eye, and the dead might not be dead and he who passed away might not have passed away, and he who went to a better world might still be wandering around our world. That's what suddenly burst out of oblivion on the day of Faisal Husseini's funeral, and it gives us no rest.

Habibi, who gave us his well-known book, The Wonderful Tale of the Pessoptimist's Disappearance, asked in his will to inscribe only three words on his gravestone: "Ba'aki Fi Haifa," which in English means, "I remained in Haifa." Faisal al-Husseini needed no such defiance. Habibi's generation passed away, and al-Husseini's generation arrived, and avowal has taken the place of denial. Here, thus, al-Husseini's "I remained in Jerusalem" became something natural, self-evident, a birthright recognized by all – well, almost all.

Official Israel, angry and sullen, was forced to act against its will on the day of the funeral. It pulled its soldiers back to the side of the road from Ramallah to Jerusalem, shut down the checkpoints along the road and opened a direct route to the mosques on the Temple Mount and the plaza surrounding them. Thus, the funeral procession became a flow of nationalism, and Jerusalem became, at least for a moment, the capital of Palestine. So, briefly, it seemed.

It was as if the departed, who was known to all, returned to life, to the sound of cheering that spilled over the walls, to wake the people and the land.

In the reception room at the Orient House, where Faisal al-Husseini used to welcome his guests, a painting hung on the wall: A glassblower sat before a flaming furnace, holding in his hand an iron rod at the end of which was an incandescent mass, as if a piece had been torn from the sun. Perhaps, one of the guests might have thought, this glowing mass, this molten glass, is a hint that the craftsman has already taken hold of the material but has not yet finished working it, and its final shape is still only a vision.

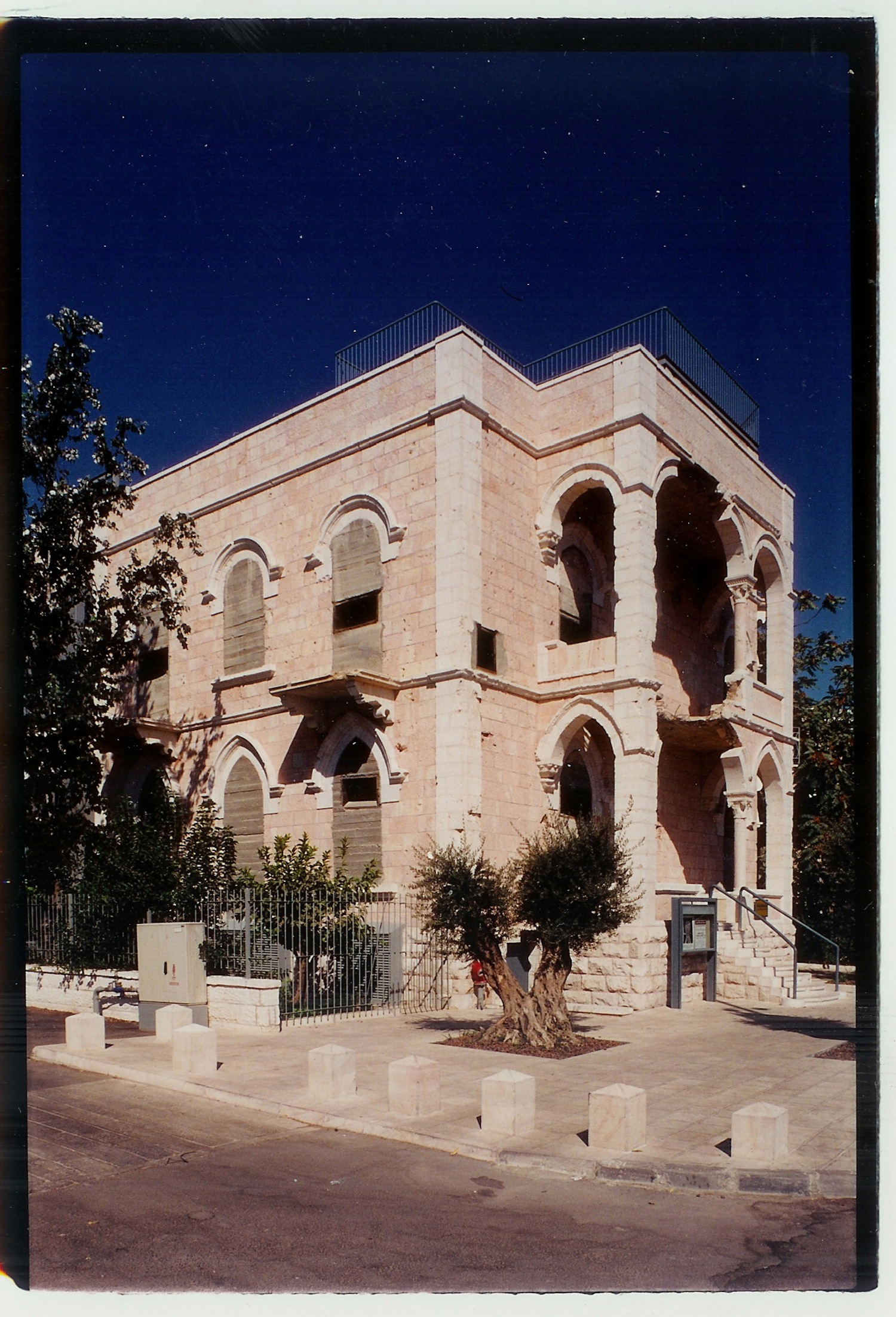

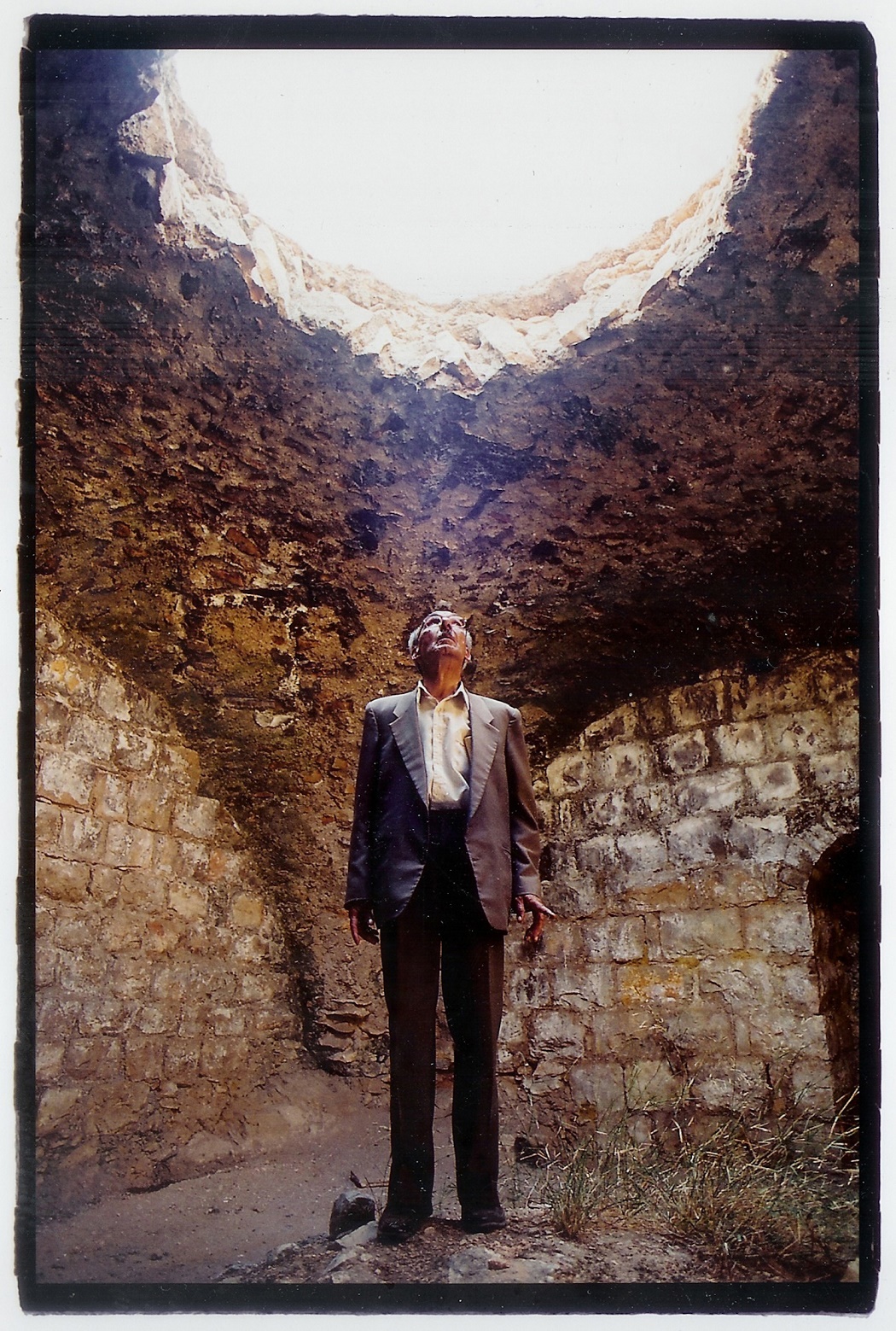

Palestinian Houses, Baramaki family, Musrara / בתים פלסטינים, בית בארמכי, מוסררה

Palestinian Houses, Akel family, Deir Yassin / בתים פלסטינים, בית עקל, דיר יאסין

Palestinian Houses, Lifta / בתים פלסטינים, ליפתא

Palestinian Houses, Rashid family, Talbieh / בתים פלסטינים, בית הארון אל-ראשִיד, טלביה

Palestinian Houses, Barhoum family, Maliha / בתים פלסטינים, בית ברהום, מלחה

Palestinian Houses, Sakakini family, Katamon / בתים פלסטינים, בית סכאכיני, קטמון

Palestinian Houses, Kalabian family, Talbieh / בתים פלסטינים, בית קלביאן, טלביה