Excerpts from the booklet:

The children of the stars - atfal al-nujuum

by Adoram Schneidleder

We who were born on the warm side of Zionism have been educated in the shadow of a dogmatic love of a land. As a result, many of us have tried so hard to convince ourselves of our love of this land that we have lost track of what it may actually mean to love a land. Through thought and imagination many of us have searched to impose love and possession.

Many times this land appeared to me from the other side of a car window on the edge of the road as I sat in air- conditioned isolation from her. She lay framed, as if in a postcard, a place I could not reach. In many places today we can only rest our questioning gaze upon her through the entanglement of the barbed wire and the fences we have laid across her. The land so cherished lies blotted beneath our obsessive struggle to possess her and to freeze her in a given imagined time. So here she now sits divided into compartments by wire and concrete, for all of us to love.

Often, at times without knowing, I have wished to experience a connection to this land that did not channel through spirals of intellectual calculation. A connection that existed before words were thought of to describe it... or to justify it. A connection that inhabited the individual through non-meditated nonchalance, like the one that leads us to sit in the shade of a tree on a hot summer afternoon, instead of next to it in the sun.

Five years ago I was given an article in Haaretz that spoke of two communities that would not give up on their right to return to their villages and their lands ever since their expulsion in 1948. The seas have been moved against them and still they return to sit and ponder, past, present and future, upon the denuded Galilean hilltops of their destroyed villages. This seemed to me an ideal context to explore the fate and future of an alternative form of attachment to this land, the form experienced by Zionism's Others: the native inhabitants, the Palestinians. I began a PhD study on the two villages.

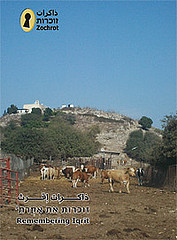

Like many others I discovered Iqrit at the same time that I discovered Bir'im. The two have been so neatly associated in the press and collective Israeli imagination that it is sometimes difficult to understand that, apart from a similar fate, the two villages do not have much to do with each other. And unfortunately, Iqrit and Bir'im are just two episodes in a vast project of forcefully transformed landscape, the victims of a nervous machinery, obsessed with possession of land and ethnic exclusion. A machinery that may have slipped out of control. We have lost a lot to this machinery. For example: the architectural expression of a locally produced equation between man and earth. Such an architectural expression was to be found in the villages of Iqrit and Bir'im... as in so many others. This has been sacrificed by the machinery. And this loss is a loss to us all. Should we now fear that the tacit but steadfast forms of connection to this land become victims in turn? Shall we bury these alternative forms alongside the scattered remains of the houses? To be trampled beneath the hooves of the cows of Shomera?

It is to the common benefit of all inhabitants and self-proclaimed lovers of this land (whether it comforts them to call it Israel, Palestine, Canaan... or whatever else), that certain individuals refuse to allow their organic connection to its earth wither away and die. Among these resisters we can include the community of Iqrit. Maybe I began my PhD searching for a more intimate knowledge of the land. What I found was people. I have been coming to Iqrit regularly since 2006. Here I was greeted with a human experience that has become and will always be a part of me. Many Iqrithawiyyeh may not know this. They have given me a fraction of their perspective, conferred upon me the honour of tasting their connection to this place, to this denuded hill and its domed church.

Iqrit has multiple backbones. There are elderly people, the ones who lived the expulsion (tahjir) of 1948. They are the ones who discovered the difficulties of exile in the town of Ramah. They are the ones who had the courage amidst the chaos and confusion of the Nakba and the creation of the State of Israel, to take their case to the High Court of Justice. They are the ones who learned of the destruction of their village on Christmas Eve 1951. They are the ones who walk the ruins of Iqrit today, still collecting figs and sabar. There are those who come, and there are those who come less, but whose presence is relayed by others. This is the generation that struggled with renewed hope in the 1970's, and marched to the Knesset. They slept beneath the stars or within the church, creating presence and walking their earth once again. There are those who are shy or for whom the pain has not found words, and others who never miss a summer camp or an occasion to open a painful window on their multilayered past. For many of them "return" has now been found in the earth of Iqrit's cemetery.

A second backbone is composed of their children. These are the ones who carried the weight of their parents' legacy amidst new challenges and a young country which regularly greeted them with the face of exclusion and discrimination. Studies, professions, economic stabilisation, they solidified a new base for the dispersed community's continued existence. They were young in the 70's and as children they tasted the renewed political struggle. Among them, many did not find it easy to extract from their parents what exactly befell them in 1948. This generation created a bridge between 1948 and today, and from this bridge they continue to search for paths today. They pursued this ungrateful task throughout the years, often misunderstood both by their parents and by their children. But Iqrit has yet another backbone. Iqrit has the children of the stars.

Maybe the most dynamic form of "return" developed by the Iqrithawiyyeh has been their regularly occurring summer camps. These camps of hope and resistance have accompanied a particularly solid group of children throughout their adolescence and early adulthood, giving rhythm to their lives along the way. These youths may not know each painful step of the political struggles of their grandparents. They may not perceive each minute intricacy of the machinery that has dispossessed them. They may not understand the motivations and unsettled spirits of their neighbours. They may not even all know which pile of ruins represents whose house. But they are at home in Iqrit. Iqrit has nourished them and in turn they nourish Iqrit. Through them life continues to pour down the path from the church to the cemetery. Through them life flows among the scattered stones, it blows through the fields, rests in the valleys and pervades the denuded hill.

How many nights have they sat, perched upon it! Once around a fire, once without, once in the cold of winter with a chilling wind, once in the spring with an evening breeze, always beneath a sky full of stars, halfway between the church and the cross overlooking the valley. They sit upon the little hill, the stones of the destroyed houses like strewn necklaces, white in the starlight. At their feet, constellations of light from the surrounding Jewish settlements lie scattered across the valleys. To the north, beyond the cemetery and the western hill, the border ridge plunges silently into the dark Mediterranean Sea at Rosh Ha- Nikra / Ras al-Naqurah. To the south the Carmel slopes to the sea in a discreet blaze of dancing lights at Haifa. Like outstretched arms the two ridges reach to embrace the sea. The youth sit, singing and telling stories until the early hours of morning, accompanied by an 'ud and the howling of the wawiyyeh (jackals).

Time and space are suspended on these evenings. Iqrit has become a ship on which they sail, carried on a wave to the star-filled sky. Across the troughs and crests of the swaying earth they sail her through the night, momentarily unhindered by the daily challenges of life in a State that wishes they would disappear. They have inherited stones and pain. They have inherited the challenges of holding the legacy together and carrying it through a sea laden with dangers to the final port of destination: al-'awdah. They are the atfal al-nujum, the ones you can see in the night, sailing on Iqrit, upon a garden of stones but so close to the stars.

Iqrit case

by Iqrit Community Association (www.iqrit.org)

The village of Iqrit lies in the heights of the Upper Galilee, some 15 miles northeast of Acre. In 1948, it numbered 490 inhabitants living in some 70 houses, all of them Catholic Arabs.

Iqrit lands spanned 24,591 dunams, of which 16,012 were privately owned and 8,000 were under ownership dispute with the neighboring villages of Fassouta and Me'ilia. Iqrit's inhabitants made their living raising crops and herding sheep, goats and cattle. They worked closed to 4,500 dunams of seasonal crops, including mainly tobacco, legumes, olive groves, figs, pomegranates, and grapes, while the remainder of their land was devoted to grazing.

The village had one elementary school, two olive presses, two granaries, two springs and dozens of rainwater storage wells dug in courtyards and orchards around the village.

Iqrit's tragedy began on October 31, 1948, when Battalion 92 of the Israeli Army arrived in the area as part of Operation Hiram, undertaken to complete the Israeli occupation of the Upper Galilee and deploy forces along Israel's northern border. The army entered the village without any resistance, in full coordination among village representatives, the military command and Jewish neighbors of Kibbutz Ayalon, who accompanied the armed forces as they entered the village. While army officers and troops entered the village, all the inhabitants remained in their homes and continued to lead their normal life, fearing no violence or injury.

After about a week, a commander contacted village representatives to ask that the inhabitants vacate their houses for a period of two weeks, since it was the army's intention, as he put it, to conduct training and other military activities in the area which would threaten the villagers' lives. The commander promised the village priest and other representatives that the evacuation would be for two weeks only, and suggested that the villagers leave their belongings at home and take only food and water with them. On November 8, the inhabitants of Iqrit were taken by army trucks and cars to the village of Ramle, about 25 minutes ride. Fifty men and the priest were left behind to watch over the houses and belongings.

When two weeks had expired and subject to their understanding with military authorities, the villagers contacted Rame's Military Governor and asked for his permission to return to Iqrit. (In those days, the Galilee was under martial law and any travel by Arab civilians was subject to the local commander's approval). To their astonishment, the Military Governor refused, and did so repeatedly on several later occasions. In time, it was revealed that the original request to evacuate Iqrit for only 14 days was actually designed to mask a deliberate scheme to expel the villagers from their homes. After nine months, Iqrit's lands were declared "restricted military area", the army evacuated the villagers who had stayed behind and denied civilian access to the area.

When it finally became absolutely clear that the foot-dragging was disingenuous, to say the least, and that there was no intention of letting the villagers return to Iqrit, they pulled their resources and took the brave step of appealing to the High Court of Justice to order the Minister of Defense and the Government of Israel to let the villagers return home. Their appeal was accepted, and on July 31, 1951, the court made a landmark ruling ordering the minister to allow the villagers of Iqrit to return! This ruling is yet to be implemented.

In order to prevent any possibility of return, the Israeli army committed the crime of detonating and destroying the village houses on Christmas Eve, December 24, 1951. All houses were demolished, except for the church building and cemetery!

In 1953, the State of Israel seized Iqrit's lands under the Expropriation for Public Purposes Law which allowed such land takeovers for defense or agricultural development purposes. Under this law, Iqrit's lands were now owned by the state and, from 1960 onwards, its Land Administration.

Over the next several years, under the shadow of the martial law in the Galilee area, Iqrit's inhabitants found it difficult to rally public support for their struggle, not to mention pressure Israeli governments into concessions. The displaced villagers' campaign included little more than contacting this or that official to receive promises that were never kept. This went on until the Military Administration of Palestinian villages was abolished in 1966, when the elders of Iqrit came to the village and announced a sit-down strike pending full return. At the same time, while the sit-down was in progress, the church building was renovated and the villagers resumed their prayers there. The cemetery was also renovated and became the only burial spot for all Iqrit families, an arrangement formally approved by Israeli authorities which is in force to this day.

Significant public pressure began in the early 1970's and was led by Bishop Joseph Raya, who managed to rally broad-based public support by both Arabs and Jews. This phase of the struggle culminated in the massive demonstration in front of the Israeli Government buildings in Jerusalem, and the hunger strike in front of the Israeli Parliament or Knesset.

Ever since the displacement, government officials have been promising to redress past wrongs, and acknowledging the displaced villagers right of return. During the electoral campaign that was to raise him to power in 1977, Menachem Begin announced that his future government would let the villagers of both Iqrit and Bir'im (similarly displaced) to return to their lands – another empty promise as it turned out.

In the early 1980's, Iqrit captured the headlines once more, with the general Israeli public showing empathy and support for the displaced villagers' right to return to their homes. Many intellectuals, celebrities and artists led a public movement to promote their cause.

When the Labor Party returned to power in 1992, the late Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin appointed Justice Minister David Libay to head a ministerial committee to look into the matter of the villagers displaced from Iqrit and Bir'im and submit their conclusions and recommendations to the government. Following 18 months deliberations and meetings with government officials, representatives of neighboring (Jewish) settlements and other stakeholders, the Libay Committee presented its findings, as follows:

- There is no reason to prevent the displaced villagers of Iqrit and Bir'im from returning.

- The Israeli government should recognize the right of these villagers to return and rebuild their villages.

- It is the government's duty to assist them in doing so.

- It is the government's duty to compensate the displaced persons and their offspring for having demolished their houses and expropriated their lands.

Village representatives welcomed these recommendations as a significant breakthrough and a reasonable basis for righting the age-old wrongs. Some specific conclusions were unacceptable to them, though, and they submitted their reservations which were then negotiated between the parties. The Libay Committee recommendations, however, were never submitted for the government's ratification nor given the force of government resolution as customary in Israel.

Since the committee's recommendations were never discussed by the government, the foot dragging resumed. Hence, given the lack of any actual progress, the village representatives decided to appeal once more to the High Court of Justice, to order the Government of Israel to formally accept and implement the Libay Committee recommendations and the reservations later submitted on behalf of the displaced villagers.

The appeal was made while negotiations with government officials continued. After Rabin's murder and the elections which brought Benjamin Netanyahu to power for the first time in 1996, Justice Minister Yitzhak Hanegbi was appointed as the government's representative to the negotiations with the displaced villagers. When Ehud Barak of the Labor Party was elected Prime Minister in 1999, Justice Minister Joseph Beilin was appointed as his replacement. Both governments declared through both ministers that the Libay Committee's findings were acceptable to them and that they wished to reach a settlement based thereon. Perhaps unsurprisingly, once again it all came to nothing.

In 2002, the Ariel Sharon Government decided to reject the Libay Committee recommendations. Following this resolution, the High Court of Justice rejected the villagers' appeal but offered to the government to reconsider the matter favorably, when political circumstances allow (sic).

The governments' resolutions and the High Court of Justice's rulings, public and media apathy, and the village community's shock and disappointment made the Iqrit representatives resume their struggle for their just causes. All villagers displaced from Iqrit and their offspring live in Israel, mostly Rame, Haifa and Kafr Yasif. All community members, old and young, firmly believe in the justice of their struggle and will never renounce their right to return to their home village and resume their community life as equal citizens in a democratic state. All community members have individual as well as collective rights to Iqrit lands and assets. Based on these inalienable rights, the former inhabitants of Iqrit demand:

- Recognition by the Government of Israel of its moral and legal responsibility to the injustice suffered by the displaced persons of Iqrit.

- Return of all community members to their home village.

- Rebuilding Iqrit on its lands.

- Compensating the villagers for the demolition of their houses and the loss of their crops over the years.

- Revoking the administrative expropriation and closure orders.

The Iqrit Community Association

The Iqrit Community Association was founded in May 2009 by elected members of the board representing the villagers of Iqrit. The organization's goal is to lead and publicize the struggles of the community to gain the right to return to and rebuild their village on the lands of Iqrit.

The goals of the association are

- To work on behalf of the members of the Iqrit community for their financial, individual, and collective rights.

- Preservation, maintain and restoration of the church and cemetery at Iqrit village.

- Strengthening the sense of community and fostering and preserving a connection to the village of Iqrit.

Our vision

To rebuild Iqrit as a home for the community and their descendants, where they can lead their lives as equal citizens in the country.

Download File