Eitan: What was it like to work on the exhibit “Toward return of Palestinian refugees”?

Aviv: There was a tension in my work on the exhibit between me as an Israeli looking through the eyes of a colonialist – which is part of my identity – and my desire to attempt by my action to de-colonialize my identity. I felt the same way I did when I participated in a workshop of Israelis and Palestinians in which we tried jointly to plan for the return. Such actions have a decolonizing effect.

Eitan: Why? How do they have a decolonizing effect?

Aviv: Because it’s an attempt to free myself from the status of landowner, someone privileged, a householder, to view myself otherwise here.

Eitan: So, in the imagined return, when you’re no longer a conquerer, what are you?

Aviv: I see the possibility of being a citizen with equal rights, perhaps as part of a minority, not the majority. If we consider various possible decolonization strategies, the one I chose, because I was part of Zochrot, is to create a culture, a language, actions in the field, one of which would be planning the return of Palestinian refugees.

Eitan: You imagine your future self no longer a colonialist in a situation where the return has occurred, a citizen with equal rights, perhaps a member of a Jewish minority, but it seems to me that the very act of undertaking these decolonizing steps is liberating - the process itself is liberating.

Aviv: That’s right, by virtue of the act itself – I felt liberated, for example, in the workshop we conducted with Palestinians in Istanbul. Suddenly a new space was created, a new language, new and unfamiliar tools.

Eitan: What you’re saying makes me think that these new spaces, in which we’re creating new possibilities, are themselves realizing the return - our imaginings are bringing it about. A moment is reached when liberation from a colonialist identity is the result of the decolonizing act itself.

Aviv: Right, and every such act contributes something to me, an additional layer. Except at the beginning of the process, when it’s as if you’re facing a closed door of fear that must be entered. Many fascinating possibilities arise when you open the door.

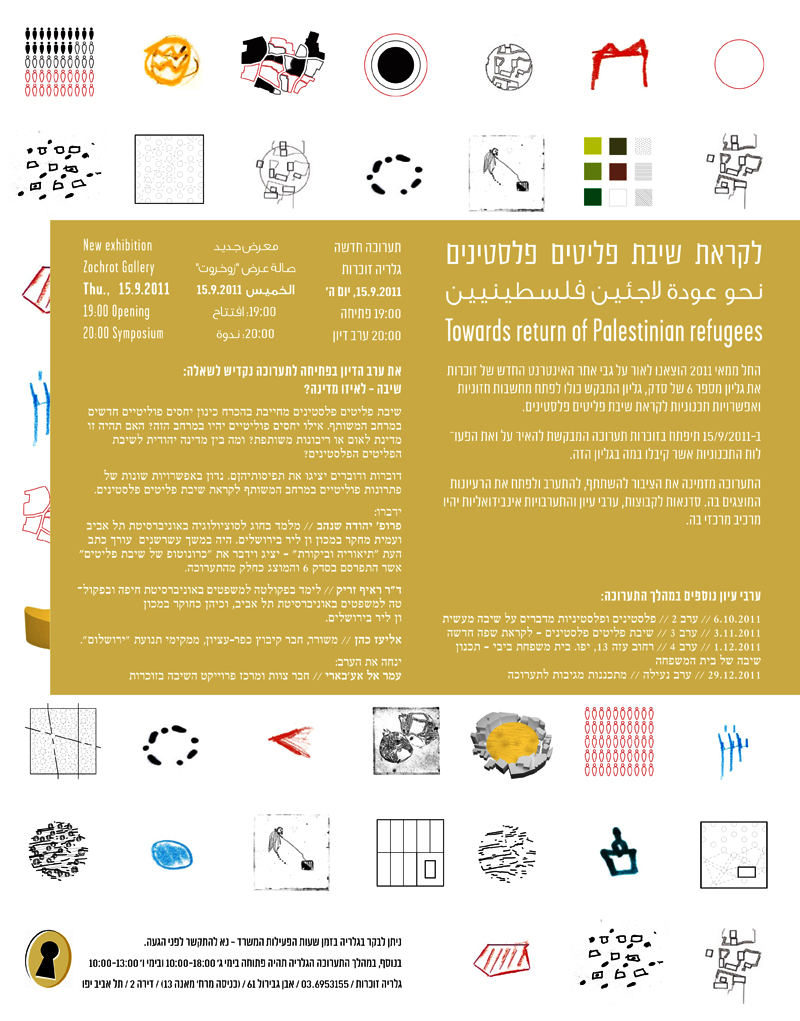

Eitan: You speak of creating a new language. Doesn’t the invitation you designed for the exhibit express it?

Aviv: I look back on my past few years with Zochrot and can see the difference between how I thought in visual terms when I began, and today. Creating an iconic image is important in design. Familiar iconic images associated with the Nakba and the return are employed today. A few years ago I tried to create such an image for the conference we held at the ZOA house on the return of Palestinian refugees. The difficulty in designing an invitation to a conference on the return of Palestinian refugees was the absence of any visual reference to the subject of the return on which to build. I chose to upend an image of Zionist pioneering women. I wanted to add a motif of return, thereby reversing its meaning.

Eitan: Did you select a Zionist image because Zionism conceives of itself as realizing the return to the homeland?

Aviv: No. I thought of Zionism as the opposite of – as erasing – the Nakba. That is, not identifying with one of Zionism’s elements, but as an oppositional response to it.

Eitan: So you took a Zionist image and upended it?

Aviv: Yes, I added a motif that to me symbolized the return of Palestinian refugees in order to reverse the meaning of the original image. My choice forced me to ask myself many questions. One had to do with the attempt to create an iconic image. Is it possible to restrict an image to a single meaning? Ariella Azoulay taught me that you can’t nail down an image to only one meaning. I wondered about using an obvious Zionist image. I finally realized that although the image I created might represent a response to Zionism, it remained a Zionist image, rather than going elsewhere. I also wondered about the entire process whose goal is to create a single, perfect image. That’s accepted advertising design practice, creating the ultimate temptation to attract consumers. That seems to me a process that’s conceptually closed, rather than open-ended. I want to be involved in a work process that forces me to delve more deeply. As far as the exhibit is concerned, the leading idea was to propose alternative possibilities of return rather than a single “correct” solution.

Eitan: So for this exhibit you designed something else, with many small images?

Aviv: Yes, one of the insights that developed was that there’s no single correct solution to the return, and that return isn’t the opposite of the Nakba or erasure of the time that has passed since then. One of the important elements in the present exhibit is the demonstration that there are many ways in which Palestinian refugees could return. Moreover, the act of preparing the displays broadens the discussion, enriches our language, and allows many people to participate in creating the new language. I tried to design the invitation to reflect this idea. I used the symbols that I identified in the keys to the various planning projects displayed in the exhibit as the elements of the new key I created. Actually, I wanted to raise questions, rather than to formulate a slogan for the return.

Eitan: Essentially, what you did was to create a lexicon of game pieces.

Aviv: I’d rather call them hieroglyphics. Because we’re trying to develop a discourse that doesn’t really exist. The key I created is a key to a new language which we’re trying to expand and invite others to participate in. I think I wanted to create a key to something we don’t really understand, that’s confusing at first. Each symbol is clear in the context of the specific project from which it is taken, but what happens to them when they’re all placed next to each other? What interested me was what happened among the symbols. In fact, I think that’s the essence of the discourse. Whoever examines the projects themselves will be able to identify the symbols I took from them, and thus better understand these hieroglyphics.

Eitan: You know, the key looks like the kind cartographers use, people who draw maps, or planners creating a spatial layout, because you used many symbols from the Counter-Mapping project, in which we drew a map. But you can also see here the traces of our colonialism in our desire to create a landscape, even if it differs from the one the colonialists created. Moreover, even in the term “the new language” that we’re trying to create I clearly hear the Zionist act of creating a new language and culture. That’s interesting, because although we think what we’re doing lacks a frame of reference or is unprecedented (when we plan the return), we do have a frame of reference – Zionist colonialism. Even our attempt to overcome Zionism reproduces some of its practices.

Aviv: That’s right. Who was it – Gadamer? – said we’re unable to act without prejudice. Obviously, we can’t detach ourselves from what we are. That’s exactly the tension I referred to. Between the desire and the impossibility to become de-colonialized. That’s exactly the reason I didn’t want to create an image that was Zionism’s opposite. Nor did I want to design something I imagined a Palestinian would create, because I’m not Palestinian and didn’t want to pretend to be.

Eitan: What kind of image or design are you referring to? One showing Palestinians returning, for example?

Aviv: Like some monumental image – a mosque emitting rays of light, for example, which appears in one of the projects in the exhibit. It’s not “my” image, I’m not Palestinian. I’d rather be a partner in something. And it’s true that you can see the key I created as a tool that can be used by those with power, but I hope they’ll use it for civic purposes, with a sense of civil responsibility. Also, when you look at the key closely, you see the symbols aren’t the usual ones found on maps because they’re hand-drawn, not generic reproductions.

Eitan: Yes, they’ve really been hand-drawn, and also appear as such in the key you designed.

Aviv: That’s why I like to compare them to hieroglyphics, which are handmade rather than technical reproductions. It’s not Miriam, a font designed by some clerk.

Eitan: Let’s go back to when you joined Zochrot, even though (maybe because) you grew up in a family that was considered right-wing, in Israeli terms. When I interviewed you for the job I asked whether you’d be able to design an invitation to a planned conference on the return of refugees. I wondered how you’d deal with that personally, as a daughter of a family whose views are very far from Zochrot’s. Can you talk about how you dealt with things like that?

Aviv: I grew up in Alfei Menashe, my father was a career military man and my family members do hold right-wing views, some of them more, some less.

Eitan: How many years did you live in the Alfey Menashe settlement?

Aviv: We moved there when I was five. Career military men lived there. I lived there until I was drafted. When I came to Zochrot my political ideas weren’t well-organized. I had various intuitions, but nothing settled. As it turned out, I discovered at Zochrot that my thinking had radical elements. Even if the expression “the right of return” frightened me, I didn’t know exactly what it meant and certainly had never thought about the actual return of refugees. Maybe if my thinking had been more crystallized I would never have gotten to Zochrot. At the beginning, I tried to conceal it.

Eitan: To conceal at home that you were at Zochrot?

Aviv: Yes. Today I’m pretty comfortable with it. I told my parents at some point because I didn’t want to feel guilty about keeping a kind of secret.

Eitan: What did you feel guilty about?

Aviv: That I held these views.

Eitan: I thought you’d feel guilty for working with people viewed as traitors.

Aviv: Yes, of course, enemies of Israel, etc. I felt guilty that I was probably disappointing them. Even though we weren’t educated dogmatically at home in a particular direction.

Eitan: But it probably went without saying that everyone held nationalistic Israeli opinions.

Aviv: Something like that. When someone wanted to annoy our parents they’d put up RATZ bumper stickers. And when someone voted for MERETZ my mother really didn’t like it. So you could understand that Zochrot was out of bounds, inconceivable.

Eitan: And today? You designed an invitation to an exhibit about planning the return, this interview will be published…will you bring them home?

Aviv: I’m not running to show them, but I also don’t want to hide anymore. I talk about Zochrot more with some members of my family, and less with others. Sometimes I invite one of my cousins to come here. When someone starts talking with me about it, I’m open. I’m not defensive; I feel more confident. I accept the members of my family as they are, each with his or her particular view of the world, and ask them to respect mine as well. Today I see it primarily as my own problem, irrespective of others.

Eitan: You mean your difficulty handling the issues we deal with.

Aviv: Yes. I’m not sure whether these issues will be as threatening to them as I fear.

Eitan: Why?

Aviv: I’m not sure why…On the one hand I answer more confidently now when someone asks me, less hesitantly, and I see that people aren’t embarrassed when they listen to me. On the other hand, when I look around at the terrible laws whose number continues to increase, I realize we’re increasingly isolated, pushed up against the wall.

Eitan: That’s very interesting…Would you like to add anything?

Aviv: You were right when you said it’s wrong to think what we’re doing lacks a frame of reference, but…

Eitan: Yes, of course, even if a frame of reference exists, precedents, tradition, we’re definitely trying to create a crack, at least, if not actually fracture the reality around us. We’re not just another nuance of the spoken language, a minor deviation. In a sense, we definitely want to create a new language. But now, as we speak, I’m reminded of Zionism’s pretentious aspiration to create a new world, a new human being…I have to smile when I think that we in Zochrot share some of those Zionist pretensions. We’re very naïve; there’s something absurd about us. It’s like looking back at the early Zionist activists and seeing how ridiculous and innocent they were. But I also think that’s wonderful, overwhelming. I see that enthusiasm in you when you talk about creating the new language. You’re embarked on an adventure.

Aviv: That’s right. There are the early, aggressive Zionist posters inspired by contemporary Russian design. I’m not interested in doing something like that (laughs).

Eitan: Why did you decide to place a large round table in the middle of the exhibition space, and display the projects on it?

Aviv: I knew from the outset the exhibit would include something round. I just knew it. The heart of the exhibit, in a material sense, is the five planning projects. I chose to display them on the round table, in large folders. It was important to me that the projects be near one another. Like with a language, where the juxtaposition of words creates meaning. I think this form of display strengthens the notion of open discourse, as opposed to choosing one correct solution. I imagined people seated next to one another looking through the folders, mixing everything up, moving from one project to another, talking to whoever is sitting next to them.

Eitan: There are additional materials also, round about…

Aviv: Sekek 6 – on which the exhibit is based – contained additional texts dealing with the return of Palestinian refugees. I didn’t want to omit them. Think of the circle – these materials form the outer ring, enveloping the products of the planning process. They expand on and illuminate the plans from different perspectives, providing depth and context. We put these materials in drawers hung from the walls around the table. Five posters hang between the drawers, one for each project, each with a short explanatory text. The exhibit is trilingual, in Arabic, Hebrew and English, because it’s clear to us that discussion of the return can’t be carried out solely among Hebrew-speaking Israelis. Two videos are also part of the exhibit. One shows interviews conducted on the streets of Jaffa, asking passersby how they would feel about Jaffa’s refugees returning. The other was created especially for the exhibit, in which refugees from Yaffa in the Balata refugee camp, in Nablus, were asked to imagine returning to Yaffa. The result is interesting and not, as I’d feared, a mirror image. The two videos, the Power-Point presentation in the background, and the space on which visitors to the exhibit could write comments, create an additional circle. It echoes from a distance the project of return itself. But it is also an essential element in the discourse as a whole, and advances it.