Liat Rosenberg, Director of Zochrot:

Zochrot has been working for more than ten years to encourage recognizing, accepting responsibility for and rectifying the crime of the Nakba in order to bring about reconciliation. “Once Upon a Land” not only travels through the past and present, but also through the future that’s latent in our surroundings. The book is an act of truth and reconciliation, because reconciliation starts with awareness, awareness of what is not present, what has ceased to exist around us, what has been concealed and erased not only from the physical space but from the personal space as well. Suddenly every remnant is exposed. The acts of recognition transform the book into a civil-political deed, a confluence of physical and personal space. Those whose awareness developed as they worked on the book have made possible the growth of awareness among those who read and use it to guide their travels.

Umar al-Ghubari, Zochrot’s tour coordinator:

It’s important to put the Palestinian Nakba into Hebrew. There are many ways of describing this book which may impose too much upon it. The book’s preface is overwhelming; everyone can find in it what they’re looking for. The preface says that the book is an invitation to recognize the Nakba, to become aware of it in many ways. The preface says that the book is, first and foremost, a practical book as well as an act of resistance to a national monopoly. But in addition to what it is, the book is careful to make clear what it is not – afraid that the book might be viewed as an act of colonialism, the preface insists on eliminating any traces of colonialism and claims that it’s a decolonizing act. I, as a Palestinian, am happy that the book recognizes the colonial reality. That’s a progressive political statement that makes possible an important and effective conversation between Israelis and Palestinians. I see the book’s Arabic text more as a contribution to the act of decolonization and less as a practical help to the Arab reader. I’m referring to a book which has also an Arabic title which no one has yet mentioned. The book will be known by its Hebrew title. The book raises interesting issues regarding translation to Arabic. It’s supposed to be faithful to the Hebrew original in order to get its message across, but sometimes the translator chose an Arabic word more appropriate to the reader of Arabic. I’d rather view the language as presencing the Palestinian Arab identity – a recognition expressed by the book’s Arabic text, even if the translation is sometimes clumsy. The book addresses the dimension of memory, the obligation to tell the story, at which point its responsibility ends. Zochrot tries to use the past to see the future in order to bring about reconciliation without ignoring recognition and redress. The book offers recognition and identification, but doesn’t go beyond them. The Arabic text is appropriate to the book’s political outlook, which must also be corrected.

The book’s designer, Aviv Gross Alon, chose to draw lines similar to those used to mark Israeli hiking trails, so that the book becomes a brilliant decolonizing graphic act. She used forms derived from the Arabic letters spelling the names of the destroyed villages included in the books.

Noga Kadman, researcher and writer for human rights organizations, guides tours dealing with the conflict, investigated how the villages were forgotten:

I used to work for the Mapa company which publishes guides to touring Israel. Because of the lack of information about the Palestinian villages I thought it would be a good idea to prepare a guide like this, since many of the villages are found in places where Israelis hike. They’re located where earlier settlements once existed; they contain archaeological sites; they have springs which attract hikers. I proposed preparing such a guide but the company shelved the idea. I’m glad it’s now being realized. The initial idea was to prepare a guide in a style and format similar to those which exist, but the text was written by many authors, from different fields, and each wanted to present her particular viewpoint. That’s why there’s variation among the texts and photographs in the book. I prepared and wrote two of the tours in the book. This involved extensive research into the history of the locations. It was a significant intellectual and emotional experience for me. I discovered an entire, rich new world I hadn’t previously known. I grew up in Jerusalem; when I was a child I was often taken to Lifta but we never heard about the history of the village. I remember the sense of mystery and fear – a desolate ancient site that had always been in ruins. Only after many years did I realize that Lifta had until recently been a vibrant, living village, full of lives which had suddenly been interrupted, and that was a revelation. Israelis know there used to be Palestinian villages, but they don’t really know what the uprooting of the refugees actually means. Sometimes even this basic knowledge is lacking; people don’t know there had been an Arab village, nothing refers to it, and I wondered what the hikers even know about the places they reach. In my thesis I mapped the destroyed villages onto hiking maps and discovered that half of them are located on Israeli hiking routes, so Israelis are exposed to the sites. I visited those sites and learned what hikers are told about them. Most of the villages are ignored; mentions tend to be haphazard and superficial, focusing on sites where ancient Jewish localities once stood or referring to the past hostile relations between Jews and the former Arab residents of the village. Sometimes cultural traditions are described but without reference to the Nakba; sometimes there’s only a symbol indicating the existence of an unnamed point in the landscape.

The same is true of the tour guides course. During the course we travelled throughout the country and I saw the differences in what people knew. The instructors noted that a particular village had once existed there, information that was part of learning about the country. But we received no additional information about the villages themselves. We didn’t visit the site of the village, as opposed to other sites such as those from the Byzantine period, for example. The course also focused on Israel’s military history so we toured 1948 battle sites and memorials. It’s important to note that we weren’t taken to any location where we were told about Arab casualties. That gives tour guides a distorted picture – Arabs as attackers, Jews as victims. That’s the picture they later transmit to participants in the tours they lead, who therefore receive only partial information. This book serves to correct these distortions, spotlighting the Palestinian aspect of what we know about the country and adds information which doesn’t appear in other tour guides.

Meron Benvenisti, geographer:

There may be a couple of people here, of whom I’m one, who are able to look at this topic nostalgically because they were there. I want to share with you my belief that there’s a certain degree of optical illusion in seeing the surroundings as comprising the Palestinian landscape – there are still people for whom it’s the landscape of their childhood. It wasn’t a foreign landscape for me. It’s a destroyed landscape which the book tries to bring again to life as my childhood landscape whose destruction I regret. I’m also the one who destroyed it and I live with this duality which makes me very sad and which accompanies me my entire life, and I’m 78 years old. My father, David Benvenisti, the geographer, took me along on his trips to these regions during the period he was involved in efforts to put Jews on the map. He took me with him, met his Arab friends, and the result was that much of my life I have sought that destroyed landscape, and I still live with it today. This duality caused great pain which makes me unable to address the subject in its direct political context because it conflicts with my Zionism, and I’m unable to consider the possibility that we brought about great damage and committed a great crime, because if that’s true what does that mean for the lives of my grandchildren? Maybe that’s why I take refuge in nostalgia, but I also think it’s possible to believe in reconciliation - which annoys those who don’t want to make amends but I wanted to add that personal note. I’m a native traveler in the land.

My home wasn’t destroyed, but a reality was created which must be dealt with and the way being proposed here seems too simplistic. The Nakba is being compared to Andalusia, the destruction of an entire culture. But it’s a great disaster for each refugee, one which cannot be remedied. However, in the final analysis, there are more Palestinians here than Jews. Half of the 950 villages were destroyed, but not all of them. Palestine-Eretz Yisrael stretches from the river to the sea. The purpose of discussing the Nakba may be to sanctify the Green Line. That is, to erase the Nakba, because if you say that the land won’t be divided then it will include the entire area and the entire history, so that in order to consider the Nakba in the state of Israel as an event during which many villages were destroyed, but whose outcome 65 years later is a source of pride because the Palestinians continued to exist in their homeland. As of now, the battle has ended in a stalemate. I don’t want to get into an argument, but this point should be part of the discussion.

Our approach to the Palestinian localities must be constructive, to see what can be done. Almost half of their area is not being used – in other words, it’s not true to say there’s no room. If we view it in terms of reconciliation then it’s part of our common history. We share the land.

Umar:

We’re not talking about a natural disaster whose cause is unknown. You said, “I destroyed it.” Why is accepting responsibility connected to the future of your grandchildren?

Meron:

That forces us to confront the question of responsibility. Israelis must accept responsibility and ask forgiveness. There are ways of dealing with this situation, and current policy must not continue. But when you make a general accusation, the accuser denies all responsibility for the outcome. The accused is outraged. I don’t want to get into the question of whether the Palestinians may not also have reasons for soul-searching. Here’s an issue which must be addressed when dealing with the topic: this narrative is correct from your point of view, but it creates a dichotomy because the accused will object and adhere more strongly to their beliefs. I have to explain to my grandchildren the uncertainties among which I live, but I can’t do so if my guilt is absolute. If the intent is to make my guilt absolute, it can have the opposite result.

Umar:

Only one tour was written by a Palestinian – the Palestinians don’t view themself as colonialists who must engage in decolonization, nor have they a need to become aware of the nakba because they were not those who caused it.

Amal Eqeiq wrote the book’s concluding chapter; she decided to discuss the photographs it contains. Amal was born in Tayibeh, she is a doctoral student in comparative literature in Washingon who writes about minority children’s literature and is conducting a comparative study among the Chiapas in Mexico and Palestinian children’s literature in Israel. She writes about popular culture, feminism, translation and the literature of the global south:

(Amal spoke in Arabic and Yoni Mendel is translating into Hebrew)

It’s important to me to speak about the Nakba in Arabic, and it’s important that the translator be an Israeli, maybe so you’ll believe him. I live in the United States; my Ashkenazi accent isn’t as prominent as it once was. It’s important to me to discuss the photographs in the book, as well as Zochrot’s memory. Maybe because there’s something unique in Zochrot’s perspective, which is why I’m focusing on the photographs. I chose three photo, which I’ve characterized as what’s familiar and good about our country. This photo (page 86) shows a donkey and fellah next to a mosque; it’s a standard Israeli photo of an Arab village. I chose two additional photos, one of an anemone (p. 254) and the second of an almond tree (p. 240). They’ve become part of Israeli Zionist culture; the flowers appear on postcards and are also referred to in Israeli music. The repressed implication of these photos is that there’s a common landscape which existed prior to the Zionist movement.

The book contains photos of the villages themselves, some of them showing Palestinian refugees returning – for example, the photo of a refugee from Lifta. The connection between tourism and the Nakba is being exploited, whether by Israelis who visit these places as tourists without understanding their political complexity, or by Palestinians, as in the Festival of Return which has become trendy but is also dangerous and exploitative.

I’m trying to understand Zochrot’s perspective, what questions it wants the reader to ask. I look at the photo of the cemetery in Beersheba (p. 486), and the one of the Bavli neighborhood (p. 150). They have a provocative aspect – ironically referring to “a land without people for a people without a land.” Regarding the right of return – if Palestinians want to return, where do they want to return to? To these abandoned places? And a third thing: these are conventional photos which could have been taken anywhere in the country. Using a term from Photoshop, I say that you could use them for a political purpose. The photo of the Etzel Museum (p. 175), and the photo of Kafr Lam (p. 117). A visitor lacking a political perspective might imagine that they’re seeing a combination of the old and the new. It’s a complex assertion, as in Photoshop, but it’s possible to identify what’s being invented here - a strategy of erasing memory. There are two photos from Jerusalem’s Talbieh neighborhood (pp. 337, 347) exemplifying the importance of Zochrot’s activity in teaching Palestine’s social history – not through destroyed villages, not through the image of the fellah, but through Palestine’s urban and intellectual history. Israel remembers Buber’s house but in doing it erases the memory of the Palestinian family who used to live there.

The importance of this research project is exactly this: that Israeli researchers are able to reach these places and prepare tour routes for them. Even though the destroyed villages in the book look deserted, I’m able to see light shining through them.

Shula Keshet, director of Akhoti, a mizrach feminist , artist and curator, social and political activist:When Tomer Gardi told me about Once Upon a Land I was very happy. I viewed it as a breakthrough with respect to the oppressive tours through the Neve Sha’anan neighborhood. People come and rewrite history, recounting it in a distorted manner, erasing parts of it. This book provides an opportunity to hear the story of the Nakba in places Jews go to, which is very important. I received the book last week; I still haven’t read it closely, but I’ve skimmed through it. My first disappointment was with the list of contributors. I realize that Israelis write about the Nakba in order to raise awareness of it, but isn’t the writing of texts by Ashkenazi Jews an example of colonialism? I think that were Ashkenazi Jews to write the erased history of Israel’s Jews from Arab lands, even as an admission of guilt, that would drive me crazy. The next stage should be one in which those who are privileged move aside and allow the people who have been oppressed to tell their story. To translate the account of the Nakba, for example, from Arabic into Hebrew rather than the reverse. But, at the same time, this is an extremely important initial step.

For me, as a mizrachi feminist, the Nakba isn’t an historical event that occurred in the past but something that continues and persists today, still has effects, emits tendrils of oppression that affect not only Palestinians but also other oppressed social groups in Israel. I see how things are connected – as soon as one people conquers another and begins to erase and oppress them, these actions seep back in to conquering society. For me, the occupation isn’t only Israel’s occupation of the Palestinians; it’s also an internal occupation, of Ashkenazim over Mizrachim.

I’d like to note the connection between Mizrachim and Arab and Moslem culture, which is necessarily a major aspect of the oppression, the erasing of history, people, culture. All of us, including the younger generation, are being erased, and that must be rectified – the privileges stemming from the occupation and the repression must be eliminated. It isn’t enough to say, “I’m guilty.” The guilt will remain until change comes.

We in Akhoti have established the Libi BaMizrach coalition which addresses the issue of cultural erasure everywhere – in Palestinian culture as well as in Israel-Arab culture and elsewhere. I must cite the Israeli educational system as a model of erasure on the broadest scale – a system dedicating most of its resources to maintaining a very restricted memory belonging to Jews from Europe. I want to mention Me'ir Gal in this connection, a mizrachi artist who created a work that became a symbol of exclusion and erasure – “Nine out of four hundred.” It’s a photo of him holding the Jewish history textbook used in the schools. Only nine of the four hundred pages are about Mizrachi Jews; all the rest are about European Jews.

I’d like to conclude with the tours. Neve Shanan is a neighborhood the dismantling of whose community has been going on for years, one which has become a poverty ghetto, the result of the racist policy which creates invisible “backyards.” Activists and organizations conduct tours there. I decided also to conduct tours, to tell the story of the veteran residents. This historical perspective includes many varied issues which activists conceal completely. And that human rights activity which is also largely infected by the reproduction of the tactic of the Ashkenazi Zionist establishment that purports to speak for all of us – doesn’t the criticism of the establishment have also to be directed at the civil society unaware of the damage it causes?

Umar:

I have no argument with Shula, but if our subject is the Nakba, could you discuss the role of Mizrachim in the Nakba?

Shula:

I think that if we’re talking about accepting responsibility for the Nakba and the occupation, then we’re part of that system and also responsible for trying to change the situation. But we Mizrachim are also victims of the Nakba in some sense. On the one hand, I accept responsibility for the Nakba as a Mizrachit, I recognize that as a Jew I’m privileged, but I think that when you say “Israeli” you include all of us in a single category and don’t see the repression of the Mizrachim and the occupation of the Mizrachim and the gentrification, etc. I think that it’s also important for you, as a Palestinian, to see this. So long as we continue to talk about Israelis vs. Palestinians and fail to understand that the oppressed groups must unite and recognize that they have to combat oppression together, I don’t know whether there will be any change. Change will occur when people recognize the oppression, the “divide and rule” of the Ashkenai hegemony.

Question:

Can the oppressed Mizrachim see the oppressed Palestinians as allies?

Shula:

Certainly. Why do you think that isn’t happening? Your question stereotypes Mizrachim. There are very many connections in Akhoti between Palestinians and Mizrachim. They deal with it there, and you can’t come from outside and claim nothing is happening.

Question:

What about the issue of class in both societies as a point of reference for the struggle. For example, Talbieh is a wealthy neighborhood.

Umar:

Zochrot doesn’t deal with that.

Amal:

Yes, Palestinian society was a class society, but the Nakba happened to everyone and the rich also became refugees.

Umar:

Recently, inspired by the book, when we conduct a tour to a Nakba site, we post the tour route on Zochrot’s web site so that everyone can follow it and become familiar with the location without having to depend on Zochrot. Now everyone can choose a route from the book or from the web site and learn about the Palestinian locations in Israel.

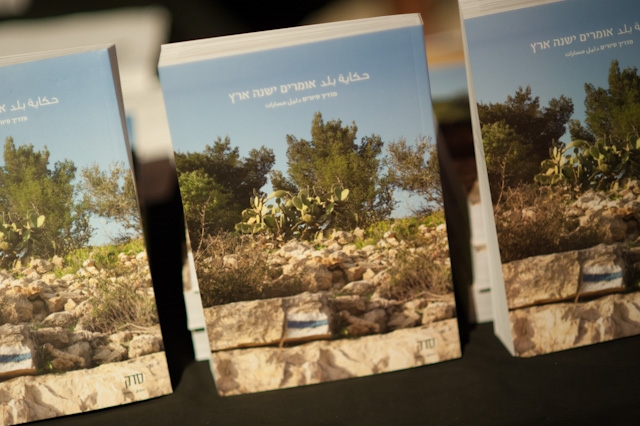

Omrim Yeshna Eretz – Once upon a Land. A Tour Guide

Omrim Yeshna Eretz – Once upon a Land. A Tour Guide

Omrim Yeshna Eretz – Once upon a Land. A Tour Guide

Omrim Yeshna Eretz – Once upon a Land. A Tour Guide