This text was published first at Yedi'ot Hakibbutz

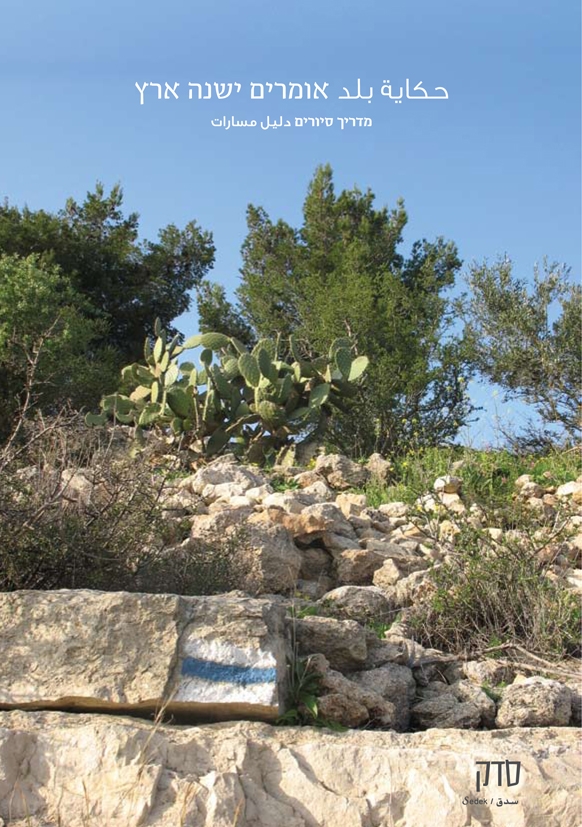

“This book,” explains Tomer Gardi, the editor, in the introduction to Once Upon a Land (a joint effort of Sedek, Pardess publishers and Zochrot), “is an appeal, an invitation. It’s an invitation to learn about the Palestinian Nakba. It’s an act of political and civil recognition of the Palestinian Nakba by means of texts and photographs.”

The guidebook offers 18 tour routes to urban neighborhoods and Palestinian villages abandoned during the Nakba, most of which were demolished by Israel. A few dozen activists and volunteers, most of them Jews and a few Palestinians, responded to Zochrot’s invitation to help prepare the guidebook – locate sites, explore them, conduct research, photograph, write texts – but only a few, including only one Palestinian, reached the homestretch, finished what they started and put together an impressive guidebook that’s different from what we’re used to – not only in its content but in its approach and style as well.

The guidebook is important because it restores a chapter that was torn out of Israel’s history books, and not by accident, one that guidebooks, particularly those which also serve as propaganda, have for years avoided confronting, denied or purposely falsified.

A journey of historical discovery

Four kibbutzim established on the ruins of Palestinian localities can be found on the tour routes in the guidebook: Nahsholim, Dorot, Gesher HaZiv and Matzuba. While the authors of some of the other routes give free rein to their outrage about injustices committed by Zionists that destroyed the pastoral Palestinian village (which, sometimes – as even the authors note – provoked, harassed and murdered Jews and the security forces before the villagers were expelled), others avoid tinting their texts in Zochrot’s monochrome and simply provide detailed, fascinating and useful descriptions of their routes.

So, for example, Ronen Ziv-Li who, together with Orna Marton, wrote Chapter 1, “Between the visible and the unseen – a journey from Achziv to Alzib, from Betzet to Albassa.” Ziv-Li, 46, from Kibbutz Rosh Hanikra, describes himself as “not at all” a political activist, and not even politically involved, nor is he a member of Zochrot. He learned about the project by chance, from an email seeking volunteers to write about demolished villages.

“I was very curious about what had existed before my kibbutz was founded and decided to go look for what was here prior to 1948,” he says. “I began in complete ignorance; I really thought and believed there had been nothing here, or at least no more than a couple of neglected houses. Wow – was I wrong! I joined the project also because I’m curious about people and places. I love travelling, in Israel and elsewhere; I’m curious about local history and the project enabled me to become much more familiar with this area. To connect with it, to connect with the people who live here with us. My love for where I live has increased as a result of the book. Life isn’t black and white, it’s not ‘they’re good and we’re bad,’ or the opposite. The complexity of where we live is one of the things that make it beautiful.”

Different voices speak the Nakba

As far as he knows, says Ronen, Zochrot is the only organization in Israel which tries to deal with the Nakba from an Israeli perspective. “I believe that the policy of concealing what occurred, along with the emphasis on ‘making the wilderness flourish,’ ‘making the desert bloom,’ etc. – doesn’t benefit us as Israelis. Zochrot makes possible a different discourse, a different way of thinking, of looking, beyond what’s accepted in Israeli political discourse, an attempt to deal honestly with one of the most important aspects of our lives here.

“Not by repeating the tired clichés - ‘they started,’ ‘that’s what they did to us’ - nor by being forbidden to talk about it, afraid to talk about it. I’m proud to live in a country in which a book like this can be published, in which this alternative discourse is possible, despite the fact that the government’s agenda is completely different from Zochrot’s. Zochrot makes it possible for us to be a democracy.”

Ronen says that during the year he worked on the guidebook he found extraordinary openness. "I think it’s also expressed in the book. Whoever looks at the fascinating, challenging, interesting tour routes will hear a variety of different voices – even very different voices – of Israelis referring to the Nakba.

“Let me tell you a story: At one point I wanted to see just how open Zochrot was and asked how they’d feel about including the “Yad Le-Yad” memorial commemorating 14 Palmach combatants in the description of the tour of Alzib and Albassa villages, whether it would fit its agenda. At no stage did any of the editors ever suggest removing it. I think the story of our lives here is complex and interesting, and we as Israelis must deal with all of it, not just the parts we’re comfortable with. Zochrot made it possible for me to undertake this interesting and important journey.”

Read with an open mind

When asked whether he agrees with the book’s introduction, that Zionism is a colonial movement, Ronen responds with a question: “Why is that important to ask? I’m an Israeli, I love living in Israel very much, I want to keep living here, and for life here to be good for my children. You have to read the book with an open mind. Not defensively. Put aside for the moment what happened in 1929, what “they did to us.” On the contrary: we’re strong, living in the country we wanted, in which we want to live. By the way,” Ronen adds, “working on the book I learned a lot about the Zionist movement that I hadn’t known before. Let me tell you – my Zionism wasn’t weakened by working on the book. I learned about Zionist activities, enterprise and planning of the kind we sorely need today.

“For example: Blowing up the 11 bridges connecting Mandatory Palestine with the neighboring countries in 1946 was an act of great imagination, strategic planning and daring. The Zionist movement acted to achieve its ideals. That’s why I’m unsympathetic to all the whining about what ‘they did to us.’

I’m also full of admiration for those who founded the kibbutz, who did all they could to achieve the ideal they believed in. We also need imagination and daring today in order to insure our future. I believe that Israeli discussion of the nakba, confronting it, is an important element in securing our existence, not only more planes or destroying nuclear reactors, but also recognizing that our way is just. And to be certain of that justice we must understand what was here, who was here, and act in such a way that will make us and our children proud of our way.

“Turning the Alzib cemetery into a garbage dump, sealing up the mosque in Albassa, failing to follow our own laws that permit adherents of all religions to worship at religious sites, failing to honor Arab citizens by recognizing the rich culture that existed here prior to the establishment of the state – none of that contributes to our security.”

Join our efforts to expose the truth

Join UsRelated Keywords

Resist the ongoing Nakba

Help us resist the ongoing Nakba

Donate NowJoin our efforts in exposing the truth about the ongoing Nakba and in promoting acknowledgement and responsibility for the injustices of the Nakba, support for the right of return and a commitment to building a just society for all in Palestine.