It stands white and circular in the middle of the Hof Dor holiday village. I’d been there dozens of times in the past. I never noticed the Sheikh’s Tomb standing on the manicured lawn. I didn’t see it. Nor did I remember the large round structure standing right on the shoreline, a few dozen meters from the water, opposite the fishing boats. I wonder about that, because Dor Beach was one of my parents’ favorite beaches; they used to go there every summer. “There aren’t any ancient buildings here,” said the woman who answered the intercom at the entrance to the holiday village. “You’re mistaken.”

I tried to convince her that I was holding a guidebook that contradicted her, but the gate didn’t open. Perhaps she also doesn’t see the Sheikh’s Tomb built of stone, surmounted by a dome, even though she passes it every day. The book I held, “Once Upon a Land – A Guide,” appeared recently; it’s intriguing. The thick book offers 18 tours of urban neighborhood and Palestinian villages that emptied in 1948 and were mostly destroyed. The book’s cover states: “These tours are to places that were once here, whose remnants we come across everywhere even if we don’t always know what we’re looking at.”

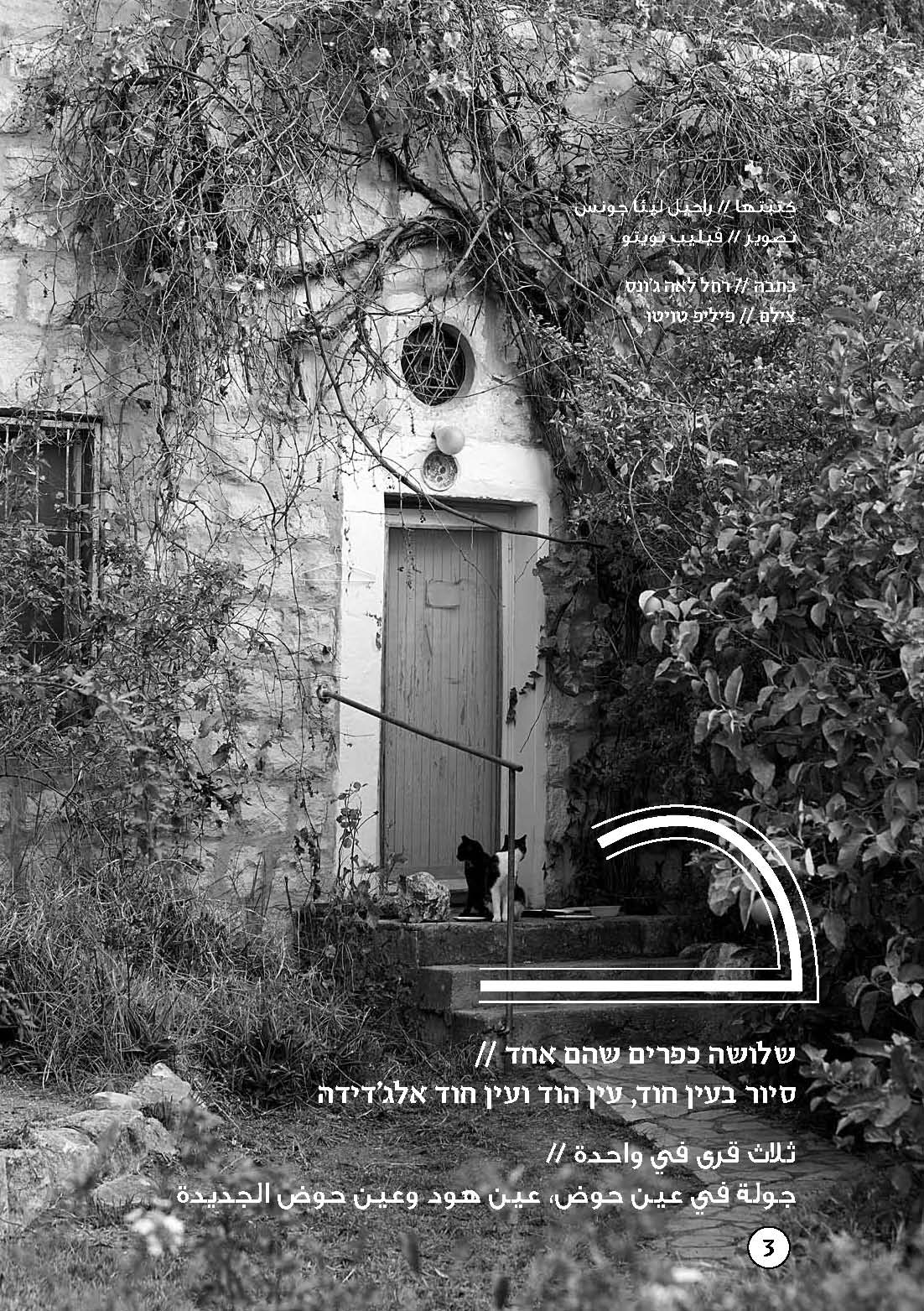

The bilingual Hebrew-Arabic guidebook was published by Zochrot and Pardess Publishers. Today we’ll follow two of its chapters – a tour of Ayn Hawd, Ein Hod and Ein Hawd Aljadida, by Rachel Leah Jones, and a tour of the HaCarmel Beach villages – Kafr Lam (HaBonim) and Al-Tantura (Dor), by Noga Kadman.

I’d visited those places before, but this time I came looking for their Palestinian past. To see what remained of the past which had been almost completely transparent to me for decades. I searched for what was visible today of the village that 65 years earlier had stood along the coast. Let me say right at the beginning that the great importance of the book lies in the fact that it was published. It documents consistently, systematically and historically (with a clear political point of view) a past we tend to ignore – just as I, before this visit, hadn’t seen the Sheikh’s Tomb at Dor. Although the guidebook is important, it’s not easy to use. It confronts the traveler with complex challenges, including an endless combination of directions and comprehensive historical account, in two languages, and a complicated and somewhat tedious layout.

Al-Tantura – Dor

On the left (southern) side of the narrow access road to Hof Dor a brown sign directs visitors to the memorial for 13 soldiers from the Alexandroni Brigade who fell here in 1948. This modest memorial is surrounded by a fence. It’s necessary to telephone so that one of the employees of the Fisheries Research Institute that’s located here will open the gate. The institute is located in a long stone building with large arches. Until 1948, the building was the school for children from the Arab village of Al-Tantura. About 1700 people lived there in the 1940’s; there were 200 buildings in the village. Almost nothing remains of them today. What little is left can be found in the Dor holiday village and in Nahsholim, near the shore. The evening prior to my visit I spoke to Yusef Am’ar, a resident of Fureidis and a grandson of refugees from Al-Tantura; he asked whether I know where the Hof Dor parking lot is located. “Yes,” I replied. Am’ar sighed and said, “Great. You’re standing on our cemetery.” Most of the village buildings stood where the parking lot is now located. You can’t see much there. Am’ar says that neither his grandparents nor his father wanted to talk about Tantura. They were even afraid to say the word “Palestinian.” “You, the victors, write the history, and we, the vanquished, don’t care today any longer what’s being written.”

I didn’t tell Am’ar, but my father, who was also called Yosef, loved to talk about Tantura. He participated in the battle for the village as a soldier in the Alexandroni Brigade, was wounded early in the fighting and hospitalized for a number of weeks. The wound left a deep scar on his shoulder which he was proud to display. Decades later he used to say, “I spilled my blood here, and what was the point of it all? What’s become of the country? This isn’t what we’d hoped for.” The claim by a number of historians, Teddy Katz in particular, that the soldiers who captured the village had massacred residents of Tantura made my father very angry. It was better not to mention it.

At the southern end of the Dor holiday village, on the lawn, among the vacation pavilions, is the tomb of Sheikh Abed Alrahman Albujeirmi who had once lived there. According to the guidebook, his relatives live today in Lebanon, Syria and Canada. A few dozen meters from the tomb, between the holiday village and fishing boats floating in the round bay that belong to residents of Fureidis, is a large, crumbling stone building – the customs house – where British officials lived. They monitored the watermelon exports to Egypt by the residents of Fureidis.

Enter the Nahsholim holiday village (north of the parking lot) to view an additional site -the glass factory. In 1882 Baron Rothschild bought land from residents of Al-Tantura and erected a huge stone building next to the Arab village. The factory was intended to manufacture glass bottles for the nearby winery in Zichron Ya’akov. Rothschild hired Meir Dizengoff to be the factory’s chemist. The entire endeavor collapsed not long afterwards and nothing was ever manufactured. In recent years the lovely building has been restored and is today an archaeological museum displaying artifacts from Tel Dor.

To see remains of the earlier history of this perfect bay, climb the hill where the Dor Beach excavations are underway, north of Nahsholim. The view from the top is fantastic. The advantages of settling at such a lovely and convenient site are obvious. Its calm bays provide boats a protected anchorage against storms.

Kafr Lam – HaBonim

You can walk from Dor Beach to HaBonim Beach along the path marked in red winding along the hilltops parallel to the coast. It’s a lovely walk that takes about an hour and a half. You can also drive to HaBonim (north on Highway 4, then west following the signs). The remains of the Palestinian village that once existed where moshav HaBonim is located today can be found right in the center of the moshav. The most obvious and impressive is the building housing the moshav offices, a library and a post office.

This impressive structure was once the home of Kafr Lam’s mukhtar. It’s possible to see the view from the porch by ascending the external stairs. The houses of Kafr Lam stood next to the mukhtar’s house. The village had about 350 inhabitants before 1948, who lived in 50 houses. Many of those buildings stood where today a broad lawn stretches north of the mukhtar’s home. A memorial to victims of the holocaust stands next to the lawn, with a quote from Abba Kovner: “Remember the past, live the present, believe in the future.” An Arab worker knelt in prayer next to the memorial. HaBonim’s greatest surprise is located on the hilltop beyond the small grove of trees – a large, impressive eighth century fortress from the Moslem period, ruined and abandoned, known as Cafarlet. According to the guidebook, this is one of the country’s few surviving fortresses with round corner towers. This could be a tourist treasure for someone who developed and took care of it, but today it’s no easy matter to make one’s way through to the other side.

Ein Hawd – Ein Hod

Not much remains of Al-Tantura and Kafr Lam. Today only a few structures testify to the lives once led there. The situation is completely different in Ein Hod. Unlike other Arab villages in the area which were almost completely demolished, it was decided in 1953 to preserve Ein Hawd’s buildings and turn it into an artists’ village – Jewish, of course. In 1954 the name of the village – Ein Hawd (“the basin spring” in Arabic) - was changed to Ein Hod.

Muhammad Mubarak Abu Alhija sits in the courtyard of “HaBayit,” the restaurant he owns (with excellent Arab food and a view reminiscent of Switzerland) in Ein Hawd Aljedeida, smoking. He has blue eyes, a piercing look and a tired smile. He glances at the guidebook I show him and says: “I don’t agree with Zochrot. Our ways differ. They want to exhume the bones of my grandfather who was uprooted from Ein Hawd. What good will that do me?”

Abu Alhija is the municipal head of Ein Hawd Aljedeida, the village established in the 1960’s by refugees from Ein Hawd a few kilometers to east of the village from which they’d been uprooted. Until 1992, the village was “unrecognized” under Israeli law; its residents did not receive water, electricity, sewers or an access road. The village was granted recognition only in 2004 and became part of the HaCarmel Beach regional council.

As a young man, Abu Alhija worked for Jews in Ein Hod, in construction. He then studied civil engineering and established the “Association of Forty,” the first organization to address the difficulties faced by the unrecognized villages. Ten years ago he opened the HaBayit restaurant in Ein Khud Aljedeidah, which became very successful.

“I’m a realist,” explains Abu Alhija. “My only problem is that the state doesn’t treat us with respect and as equals. All I want is full equality; I think the people of Ein Hod still fear us and I don’t understand why. I don’t want to return to Ein Hawd. Look how beautiful it is here. I wouldn’t trade places with them today even if you paid me millions. But people must respect one another. They insist on operating a bar serving alcohol in the building that was once the village mosque – that’s disrespectful. I’m not a religious man, but you have to respect other people. We suggested they build a restaurant in a different location, but they refuse. I was born in the new village; it’s good here, but I want to be an equal citizen and get some respect.” Later he tells us about someone who came to have coffee at the restaurant and told him with a broad smile: “Today I bought your grandfather’s house.” “I didn’t say anything to him,” recounted Abu Alhija. “I only asked, ‘Was the coffee good?’ That’s all.”

“I’ll tell you a dream, so you’ll understand, “ says Abu Alhija. “I dreamed I was in a house filled with people, but all of them were blind. They couldn’t see anything. I try to leave but can’t find the door. Then a blind man comes over, places his hands on my temples and says, ‘You’ve already received everything. Now leave.’ And I manage to find the door. Get it? They’re all blind, here in the village as well as in the country, and I manage to escape. And that’s it.”

בית המכס בטנטורה (חוף דור) / The customs House at Tantura (Dor beach)

שרידי מבצר צלבני / Crusaders Fortress remains

סיור בכפרי חוף הכרמל / אומרים ישנה ארץ / جولة في قرى ساحل الكرمل / حكاية بلد

סיור בעין חוד, עין הוד ועין חוד אלג’דידה / אומרים ישנה ארץ / جولة في عين حوض، عين هود وعين حوض الجديدة / حكاية بلد

תמונת שער אומרים ישנה ארץ, מדריך סיורים / صورة الغلاف لكتاب حكاية بلد، دليل المسارات