Info

District: Akka (Acre)

Population 1948: 14280

Occupation date: 18/05/1948

Jewish settlements on village/town land before 1948: None

Jewish settlements on village/town land after 1948: None

Background:

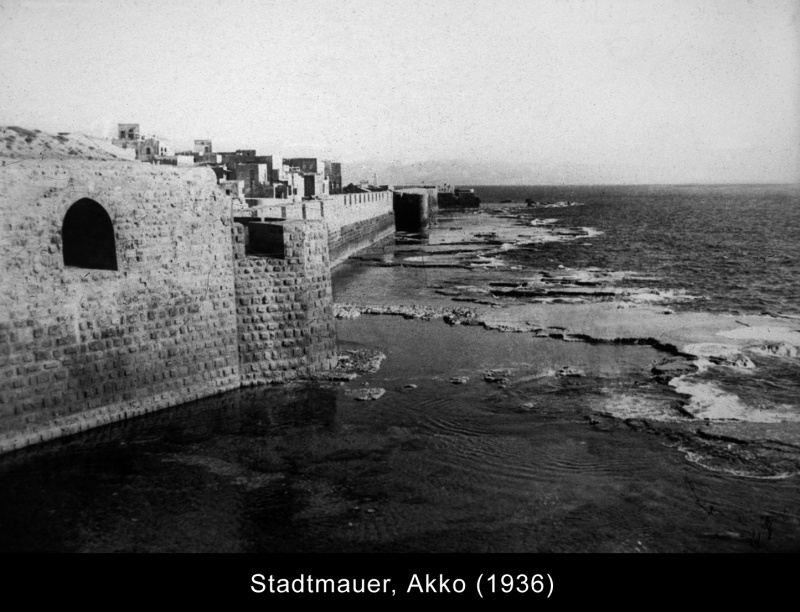

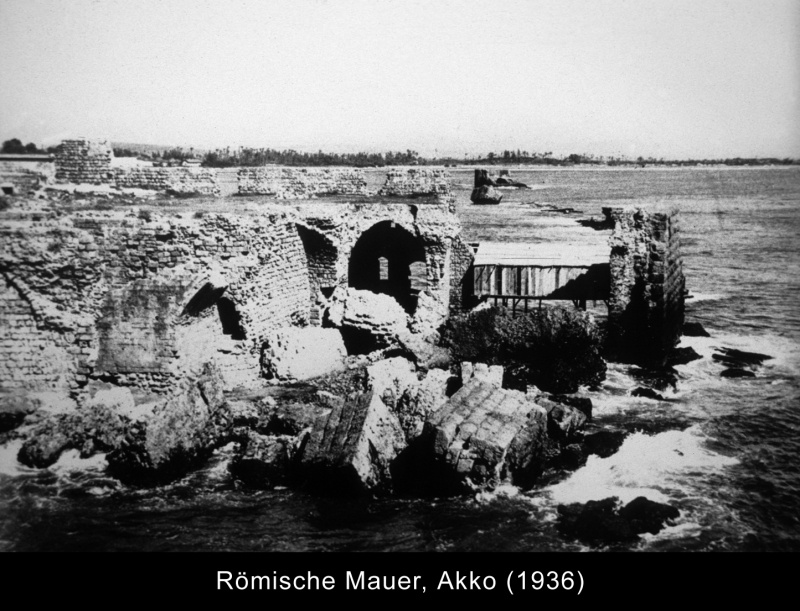

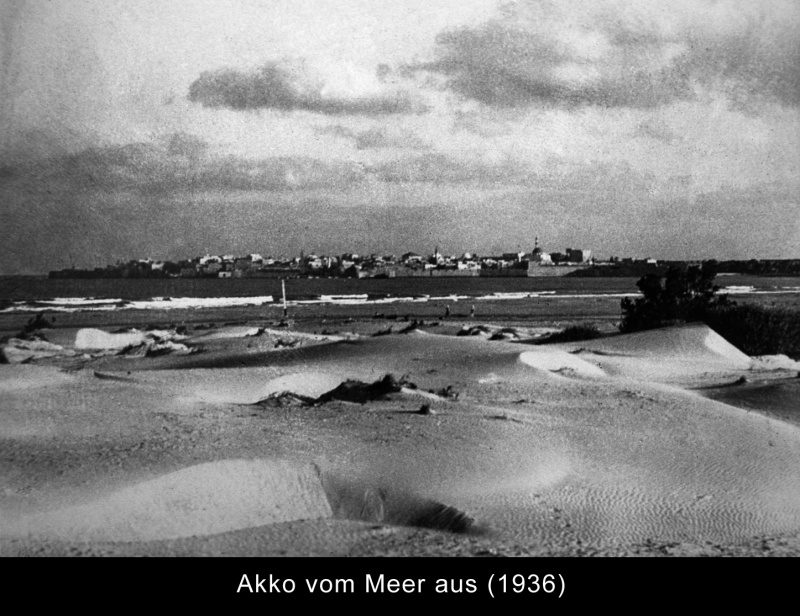

The history of Akka (often transliterated as ‘Akka) is closely linked to the history of Palestine. Akka was successively ruled by various foreign powers that benefited from its strategic location. In the 12th and 13th centuries, it was occupied by the Crusaders who renamed it “St. John of Acre” – hence its current English name – and became the leading port in the Eastern Mediterranean. After the final defeat of the Crusaders in Akka in 1291, the city lost its importance until the mid-18th century, when Zahir al-Umar (1689-1775) became the autonomous Arab ruler of the Galilee.(1) As part of his project to make Northern Palestine autonomous from the Ottoman Empire, he restored Akka’s former glory, making its port the main market for the Galilee and Damascus and fortifying its walls. These fortifications would allow Akka to successfully resist Napoleon’s siege in 1799.(2) During the late Ottoman period, Akka had to face competition by Haifa’s harbor , and saw a decline in its influence. It is only after the First World War that the city developed once again.

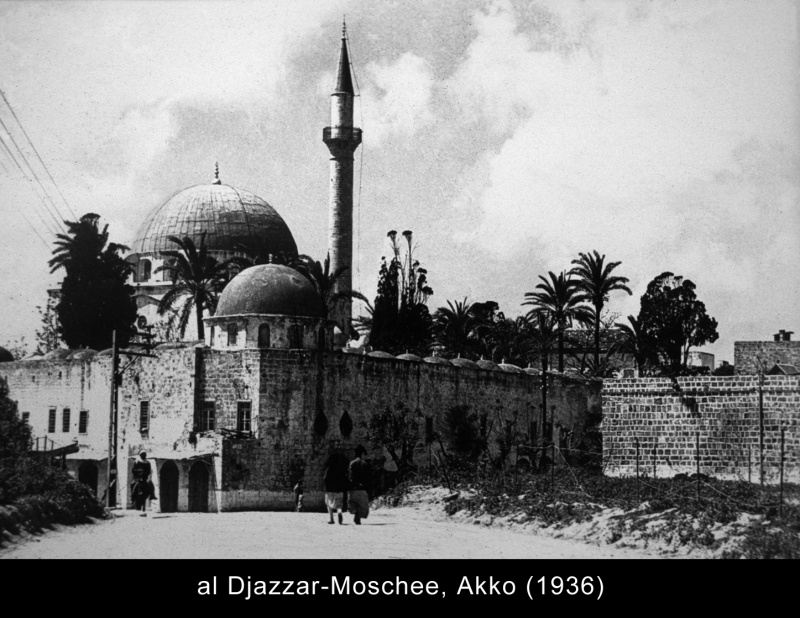

Akka during the British Mandate

During the British Mandate (1918-1948), Akka became known as an important economic and cultural center in Northern Palestine. Salma Khadra Jayyusi, a Palestinian writer who spent her teenage years in Akka, recalls: “Akka looked to joy and harmony, to an open heart that welcomed life”.(3) Throughout this period, business flourished in different sectors: pottery, copper, textile work, and of course, fishing.(4) Akka was also home to important Islamic and Christian religious schools, such as the Ahmadiyya and Terra Sancta, respectively (4).

Akka’s population doubled between 1922 and 1945.(1) Nevertheless, its urban area did not expand proportionally. Jewish agricultural settlements grew around it, making it impossible for Palestinians to reclaim the land for future enlargement (5).

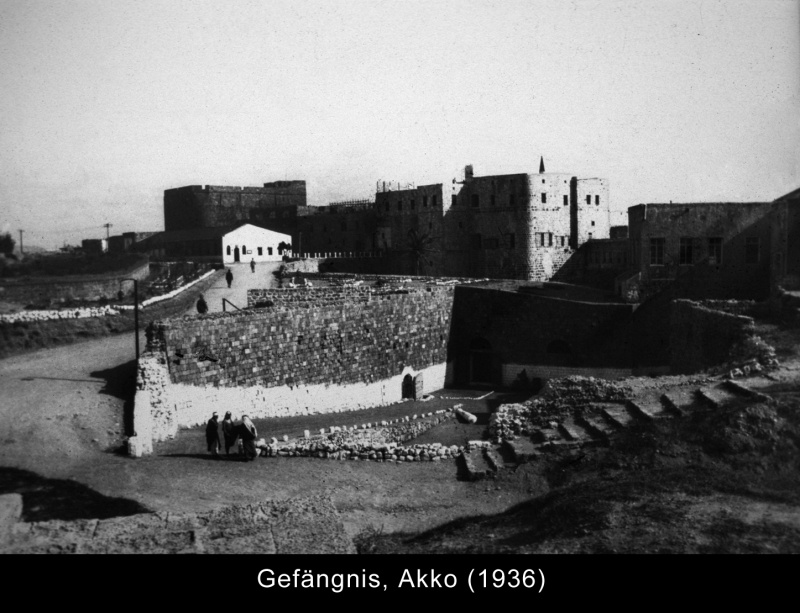

During that time, Akka also became renowned for its prison. Throughout the British Mandate, the prison walls witnessed the oppression of several Palestinian uprisings. Indeed, although the Israeli narrative only stresses the imprisonment of Zionist fighters, they were very few compared to the number of Palestinian jailed, tortured and executed in Akka.(1) In 1929, three famous Palestinian martyrs – Fuad Hijazi, ‘Ata al-Zir, and Mohammad Jamjoum – were arrested and incarcerated in Akka prison for participating in the Buraq Uprising, a wave of demonstrations and riots [U5] against Zionism and British colonialism (the latter called it the 1929 Palestine Riots). They were sentenced to death and executed on June 17, 1930. Their famous last words still resonate with today’s struggle: “At the end of our lives, we say to the Arab leaders and Muslims all over the world: do not trust the foreigners. We lived and died for the Arab cause.”(6) A few years later, during the Great Arab Revolt of 1936-39, the prison was used as a busy transit station for Palestinian prisoners headed to detention camps.(1)

This prison’s proximity enflamed political sentiments against the pro-Zionist British rule. Conferences and seminars were held, and many Akkans were engaged in political activism.(4) Strikes and demonstrations were organized to protest against ongoing Jewish immigration and land acquisitions.(3) Akka’s activism followed a longtime oppositional tradition, and relations between the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem Haj Amin al-Husseini – the main Muslim leader in Mandatory Palestine – and local leaders were generally tense.(7)

Akka in 1948

Throughout its history, Akka has always been synonymous with resistance. It resisted Napoleon’s imperial ambitions, and held out for six month under Egyptian siege before succumbing in 1832.(7) Nevertheless, Akka was occupied by Israeli forces with relative ease on May 17, 1948, three days after Israel’s Declaration of Independence.

According to Israeli historian Benny Morris, the Israeli troops were “helped by the lack of Arab national and supra-national organization”.(Morris, 2004, p.14) Indeed, tensions between the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem and Akka’s leadership prevented cooperation between local forces and the Arab Higher Committee’s militia.(7) Nevertheless, the fall of Akka was first and foremost the result of a well-engineered military strategy. To quote the war diaries of David Ben Gurion, “The strategic objective [of the Jewish forces] was to destroy the urban communities, which were the most organized and politically conscious sections of the Palestinian people. This was not done by house-to-house fighting inside the cities and towns, but by the conquest and destruction of the rural areas surrounding most of the towns. This technique led to the collapse and surrender of Haifa, Jaffa, Tiberias, Safed, Acre, Beit-Shean [Baysan], Lydda, Ramleh, Majdal, and Beersheba. Deprived of transportation, food, and raw materials, the urban communities underwent a process of disintegration, chaos, and hunger, which forced them to surrender.”(9)

The UN Partition Plan of November 1947 included Akka in the prospective Arab State. This initially gave Akka’s residents confidence and hope in the city’s capability to hold out against the Israeli forces.(7) This optimism was soon dashed by Jewish ambushes on the road leading to the city. The most tragic one took place on March 17, 1948, killing 15 Palestinian and leading to retaliation and an escalation of violence (7).

These attacks were not random, but part of the abovementioned military strategy. Indeed, the directives for Plan Dalet – conceived in March and launched in early April 1948 – specifically required the commander of Carmeli Brigade operating in the Western Galilee area to “impose a siege on Acre in accordance with the guidelines laid down in the general chapter”.(Abbasi, 2010, p.11) These guidelines included the blocking of access routes by different means (ambushes, blowing bridges) but also cutting off electricity, water, and fuel supplies, and sabotaging the resupply process.(7)

The situation worsened with the influx of refugees from Haifa in late April. Akka became overcrowded and subject to shortages of vital services. Most people could not go to work because the roads were blocked, and crime rates soared.(8) This led to a first wave of forced migration, mostly by wealthy people who managed to escape by car. People did not escape on foot, because they were afraid to cross the surrounding Israeli settlements.(10)

After Haifa was occupied by Jewish militias on April 22, they became increasingly aggressive towards Akka, raiding the city on the 25th and 26th, using mortars and machineguns to strike fear into the civilian population, and reportedly demolishing three houses before being stopped by the British.(8) According to official testimonies, the goal was undermine the will of the Palestinian to reconquer Haifa. These attacks also had a strong psychological effect. Thousands of refugees who had left Haifa and hoped they would be safe in Akka now had to flee again. Most moved to Lebanon, joined by Akka residents who also feared for their lives.(7)

By early May 1948, almost all hope was lost. Akka’s military forces barely managed to hold a defensive position, and fighters lost confidence in each other.(7) The mayor fled to Lebanon on May 11, soon to be followed by the local militia commander.(8) There were outbreaks of malaria and typhus in the city. Even though these were officially due to poor sanitary conditions, the Red Cross reported suspicions that the city’s water supply had been contaminated by the Haganah Jewish militia(7).

The success of Operation Ben Ami that saw the occupation of the villages surrounding Akka and the road linking it to Lebanon in May 13-14 left the city under total siege.(7) On the May 16, the operational orders issued to the regiment tasked with conquering Akka stated explicitly: “We have the city of Acre under siege for the fourth day. [...] The objective is to attack the city with the aim of killing the men and destroying property by burning and to subdue the city.” (Abbasi, 2010, p.20)

Due to the humanitarian crisis and lack of leadership, the Israeli forces met with little to no resistance when they began attacking the city on the night of May 16-17.(7) According to former Haganah member Hava Keller, “the accidental destruction of a water pipe by a Davidka mortar* led the residents to believe that the Israeli army possessed nuclear weapons”.(10) Fear of being utterly destroyed, coupled with the already horrendous state of the city, made Akka surrender on the evening of May 17.(7)

When the ceasefire was signed the next day,(8) the Haganah took control of what was left of the city. They asked the residents to hand over their weapons, searched the houses and imposed a curfew.(7) There was also widespread looting, with Israeli soldiers taking furniture and clothing from Palestinian homes.(11) Hava Keller recalls seeing Akka after it was emptied: “The door was open, we entered, and on the table we saw pita bread and coffee, probably the tenants in the house were in the middle of breakfast, and on the floor there were tiny shoes of a baby, I guess they didn’t have enough time to put his shoes on”. (10)

Akka after 1948

As a result of the Nakba, only 3000 out of 15,000 Palestinians remained in the Old City of Akka.(12) Until June 1951, military rule was imposed upon Akka.(1) As in the rest of Palestine, the Israeli government immediately took steps to prevent thousands of refugees from returning to Akka. The 1950 Absentee Property Law allowed refugee homes to be seized by the Custodian of Absentee Property (subsequently merged with the Israeli Land Administration (ILA)).(13) Akka was renamed “Akko”, as mentioned in the Old Testament,(1) and thousands of new Jewish immigrants were settled in the city.(12) This marked the beginning of a Judaization process that is still ongoing.

Indeed, with an Arab population representing around a third of its residents,(14) Akka is now regarded as one of Israel’s few “mixed cities”. In Akka, as in the rest of what is now Israel, the Nakba did not stop with the end of the 1948 war. To this day, the State of Israel has been using many tools to Judaize Akka as part of its settler-colonialist policies. The government encourages Jews to settle in Akka to maintain a Jewish majority in the city. In the 1950s, Jewish immigrants settled in Akka were offered houses, clothes and furniture that used to belong to Palestinian who fled the fighting in 1948.(11) Settlers were accommodated in upper class neighborhoods outside the Old City. More recently, in 2007, the ILA gave three buildings in the Old City to the Ayalim settler association, intent on promoting Jewish settlements in the Galilee, an area with a small Palestinian majority.(13)

Conversely, as in other mixed cities, Israel applies many kinds of pressure on Palestinian residents to “encourage” them to leave Akka.(13) With 85% of Palestinian properties in the Old City owned by the ILA,(12) the majority of the Palestinians in Akka have to rent their houses from organizations affiliated with the Israeli government. These housing authorities do not allow Palestinians to renovate or make any changes to their houses, by systematically refusing any request on a discriminatory basis. This makes living conditions unbearable and Palestinian residents “choose” to abandon their houses because of unsanitary conditions, or become evicted by the Ministry of Housing that is authorized to demolish them.(14) This phenomenon has affected hundreds of families, and led some of them to leave Akka for neighboring villages.(14) In 2008 [U11] alone, 240 homes were shut down, and 160 families were facing eviction orders.(13)

Most of Akka’s Palestinian residents are of low socioeconomic status. The city has one of the highest unemployment rates in Israel, and its Palestinians suffer from a weak education system, as well as a lack of healthcare, social services and public infrastructures.(11) Moreover, all Palestinians in Akka face many forms of racism and harassment, such as “Death to the Arabs” graffitis, vandalizing of their houses and cars, and physical attacks.(13) Israeli settlers ironically accuse them of being “squatters” or “invaders” trying to take the city from the Jews. Violence particularly escalated in 2008, during the Jewish fast of Yom Kippur, when rioters attacked 14 Palestinian apartments.(12)

Since the 1970s, the Israeli Government is also active in promoting tourism in Akka.(12) This involves concealing the city’s Palestinian heritage and highlighting its Jewish and non-Palestinian character – emphasizing its ancientness and ignoring its recent past by focusing attention on Crusaders and the Ottomans.(13). Tourism intensified the gentrification process, with the building of beautiful houses along the shore to attract settlers and tourists.(12)

---------------------------

This Article was written by Zochrot in August 2017. Special thanks to Manon Morrier for her research.

Reference

(1) Alternative Tourism Group (2005). Palestine & Palestinians. Ramallah, Palestine: ATG.

(2) Philipp, T. (2003). Acre: The rise and fall of a Palestinian city, 1730-1831. Journal of Palestine Studies, 33, 98-100.

(3) Handal, N. (2015). The city and the writer: In Acre with Salma Khadra Jayyusi.

(4) Mansour, J. (2013). Acre and Haifa: Sisters on two sides of a single bay. Jadal, 18, 30-36.

(5) Acre (2007). In M. Dumper & B. Stanley, Cities of the Middle-East and North Africa: A historical encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

(6) Al Jazeera (2008). Episode 1, Al-Nakba.

(7) Abbasi, M. (2010). The fall of Acre in the 1948 Palestine war. Journal of Palestine Studies, 39, 6-27.

(8) Morris, B. (2004). The birth of the Palestinian refugee problem revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

(9) Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. (2014). The Nakba: Flight and expulsion of the Palestinians in 1948.

(10) Zochrot (2006). Testimony of Hava Keller: The most beautiful village I have ever seen.

(11) The Arab Association for Human Rights (2014). Acre: A City of Development and Neglect.

(12) Tarabut (2011). Acre facing the old and the New Colonizers.

(13) Barghouti, E. (2008/09). Akka: A Palestinian priority. Al-Majdal, 39/40, 18-26.

(14) Sabbagh-Khoury, A. (2013). Palestinians in Palestinian cities in Israel: A settler-colonial reality. Jadal, 18, 7-23.

* The Davidka (“Little David”) mortar was produced by the Haganah’s underground military industry. Inaccurate and unreliable, it was deliberately designed to make a loud noise, so that its main effect was to terrorize civilian populations rather than hit military targets.

Videos

Video in Arabic with English Subtitles.

Benyamin was born in 1928 and enlisted in 47' to the Engineering Corps. Yocheved was born in 1929 and enlisted in 47' to the Signal Corps.

Hava Keler enlisted in the Hagana when she was in the 9th grade. in the 1948 she was not an offical soldier becaues she was a Kibbutz member. Kibbutz members were considered a kind of local militia.