Info

District: Tiberias

Population 1948: 2730

Occupation date: 18/07/1948

Occupying unit: 7th brigade

Jewish settlements on village/town land before 1948: None

Jewish settlements on village/town land after 1948: Givat Avni, Lavi, Golani Industry Area

Background:

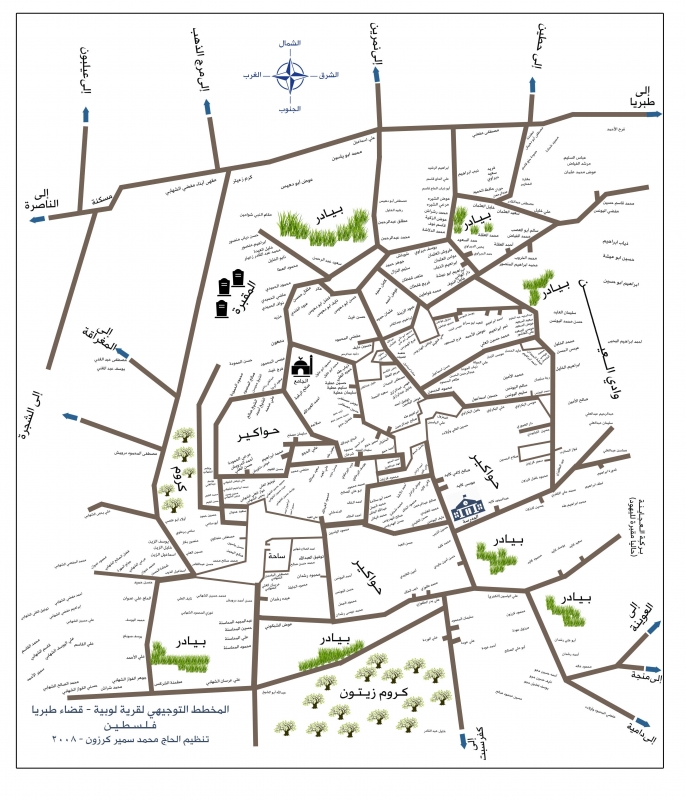

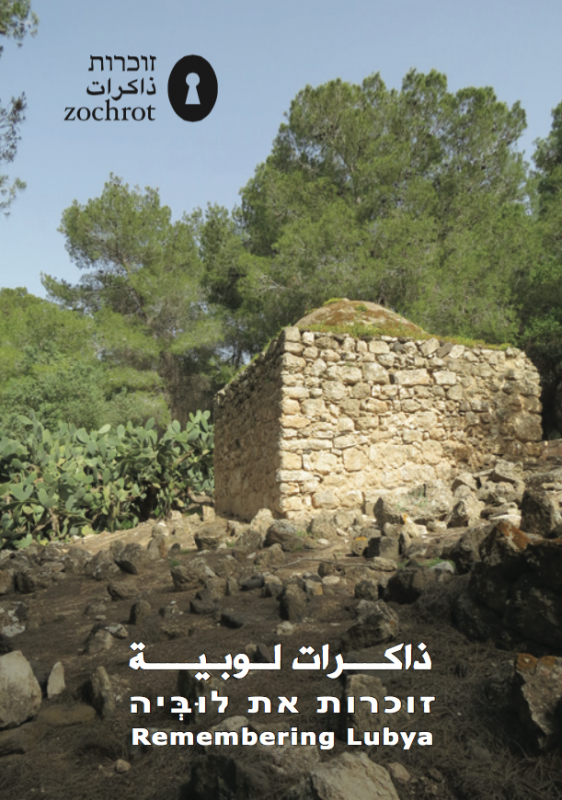

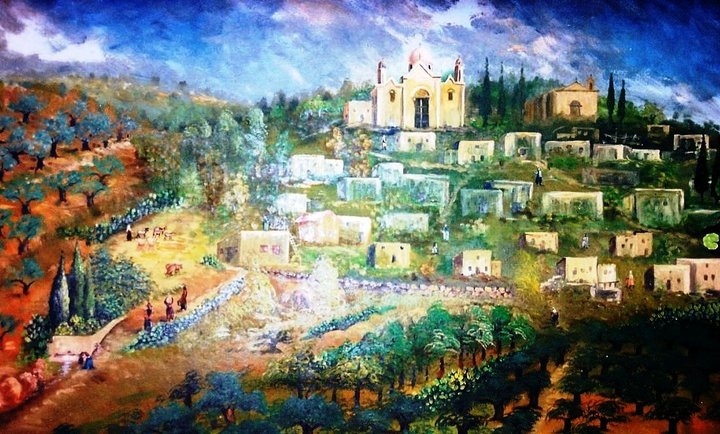

Lubya is a destroyed Palestinian village located in the north of Palestine, today in the north of the State of Israel, 10.5km west of the town of Tiberias and Sea of Galilee, on a hill at an elevation of 300m, just above the Golani (Maskanah) interchange, one of the major road junctions in the north of Israel. Lubya's architecture was that of a typical hill village, built of cubic houses, most of them made out of stone with vaults, domes and flat roofs. The houses were clustered on the hilltop between olive trees, fruit groves and threshing fields. Most of the fertile fields were situated in the flat area below the village and the land was known for its production of quality wheat in the fields of the Tar’an depression. Lubya’s community was composed of seven clans (hamulas), each concentrated in a different part of the village. Its rich land and water sources made Lubya a prosperous village, with reputation for generosity and bravery.

Adjacent pre-Nakba Palestinian villages included Tur’an to the west, Nimrin to the north, Hittin to the northeast, and al-Shajara to the south. Apart from Tur’an, each was also depopulated by Israel in 1948.

History

The village was built on previous settlements and was therefore also a village of archeological history. Lubya is located near the site of Khan Lubya, which is filled with the ruins of a pool, cisterns and large building stones. This site was probably a caravansary in medieval times and may be the one was mentioned in the Talmud as Caravansary “De Lavie”.

Known to the Crusaders as Lubia, the village was a rest stop for Saladin's Ayyubid army prior to the Battle of Hattin in 1187. It was also the birthplace of a prominent 15th-century Muslim scholar, Abu Bakr al-Lubyani, who taught Islamic religious sciences in Damascus.

During the Ottoman era, Lubya belonged to the nahiya (district) of Tiberias. In 1596, the village was required to pay taxes on its goats, beehives and olive press. Its population was recorded as 182 Muslim families and 32 Muslim bachelors. The Ottoman governor of Damascus, Suleiman Pasha, died in the village while on his way to confront the rebellious de facto Arab ruler of the Galilee, Dhaher al-Omar.

A 1799 map by Pierre Jacotin indicates the place as Loubia. In the early 19th century, a British traveler, James Silk Buckingham described Lubya as a very large village on top of a high hill. Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, a Swiss traveler, referred to the village as "Louby" and noted that wild artichokes covered the village plain. American scholar Edward Robinson, who passed through the village in 1838, noted that it had suffered greatly from the Galilee earthquake of 1837, with 143 villagers reported dead.

In 1869, Mark Twain mentioned the village in his travel book, The Innocents Abroad: “We jogged along peacefully over the great caravan route from Damascus to Jerusalem and Egypt, past Lubia and other Syrian hamlets, perched, in the unvarying style, upon the summit of steep mounds and hills, and fenced roundabout with giant cactuses”.

In 1875 French explorer Victor Guérin visited the village, which he called Loubieh, and estimated its population at 700. He further noted that: "A house built of cut stones of medium size in the direction of east and west appears to occupy the site, and to be built out of old materials formerly used for a Christian Church."

An elementary school was established in Lubya in 1895 and remained in use throughout the British Mandate era until 1948.

British Mandate Era

In the 1922 Census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities the village population was 1,712, increasing to 1,850 in the 1931 census.

According to the Palestine Government's village statistics, by 1945 Lubya had a population of 2,350. All its inhabitants were Muslim. Lubya was the second largest village in the Tiberias District in terms of area during the British mandate period, its total land area was 39,629 dunams (3,963ha). Of this, a total of 1,655 dunams were allocated for plantations and irrigable land, 32,310 for cereals, and 1,500 were planted with olive groves. The village's built-up area was 210 dunams.

1948

During the 1948 war, Lubya was defended by local volunteers and Arab Liberation Army (ALA) militias. In the early stages of the war, village forces constantly skirmished with the Zionist militias, which would soon become the Israeli Army. The first Israeli raid on the village (as well as on nearby Tur’an) occurred on January 20, 1948, leaving one Lubya resident dead. On February 24, local and ALA militiamen ambushed a Jewish convoy on the village's outskirts, causing several casualties.

In early March, Israeli forces attempted to open a route between Tiberias and the Israeli settlement of Sajara, which required attacking Lubya. During the attack local militiamen repulsed the Israelis, killing seven and losing six of their own.

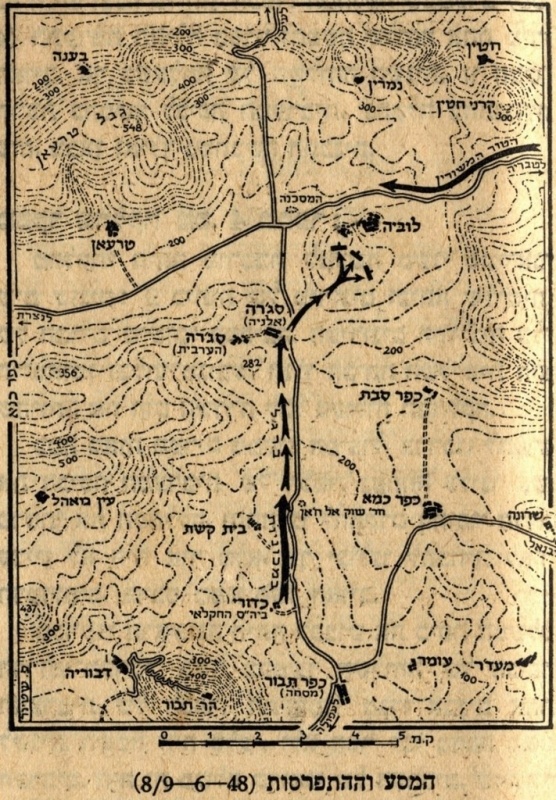

In early June, Golani Brigade’s 14th Battalion was ordered to take Lubya and "expel its inhabitants." However, the attack failed, due to heavy resistance by the villagers.

The ALA attacked the Jewish town of Sejera on June 10 at a time when a truce was being brokered between Lubya's militiamen and Israeli forces. After the truce expired on July 16, Israel launched Operation Dekel, capturing Nazareth at the start.

After news of Nazareth's fall came, the majority of non-combatant village residents fled northward towards Lebanon or to nearby Arab towns, being ‘terrified’, according to former inhabitants of Lubya. The ALA also withdrew, leaving the local militia to confront incoming forces. When a single Israeli armored unit appeared outside the village, the militia retreated and left the village. The few remaining residents reported that Israeli forces subsequently shelled Lubya, demolished several houses and commandeered many others. The village buildings were finally demolished in 1965.

Present-Day

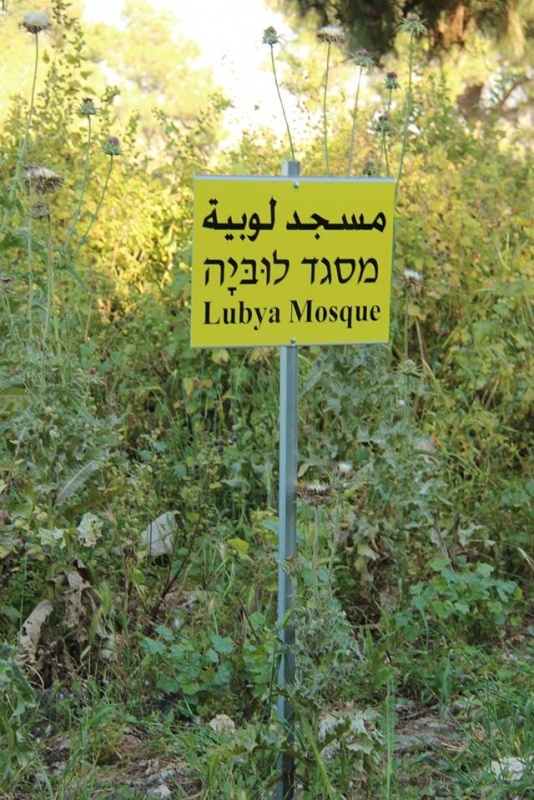

The erased village is now covered with a pine forest called Lavie Forest, part of which is called South Africa Forest. The village’s extensive lands are now occupied by Kibbutz Lavie, Giv’at Avni communal settlement, part of Tiberias’ Neighborhood D, the Golani Industrial Park, and the Jordan River Village camp for chronically ill children.

After 1948, the majority of Lubya’s refugees lived in refugee camps in Lebanon, Syria and Jordan. A few families remained in Israel as internally displaced persons (“present absentees” in the Israeli legal jargon), mostly in Dayr Hanna in the Galilee. After the Sabra and Shatila massacres and PLO’s subsequent evacuation from Lebanon (completed in 1985), many Lubya refugees left for Europe. By 2003 about 2,000 were living in Denmark, Sweden and Germany.

Recently, as a result of the civil war in Syria, some of Lubya’s refugees were killed in Syria, mainly in al-Yarmuk Refugee Camp. Most of the refugees of al-Yarmuk, including those from Lubya, had to leave it, and many fled to Europe.

The number of the Lubyan refugees and their descendants living around the world is currently estimated at about 40,000.

Palestinian Absentees and Israeli Law

By Shmuel Groag

The loss of the villages in 1948 marked the end of Palestinian dominance in Western Palestine on several levels: physical, legal and cultural. On the empty villages land the new state of Israel built 350 new Jewish settlements in five years, while enlarging dramatically the amount of state-owned land to 93% of the total land area, most of it expropriated from Palestinian owners.

The way to appropriate the refugees land was through the 1950 Absentees’ Property Law and the 1953 Land Acquisition Law. According to the former, every Arab who was not in his place of residence on a certain date, whatever the reason, was considered an absentee. Subsequently, the Land Acquisition Law gave absolute and retroactive confirmation to the transfer of internal refugees’ lands to state ownership. Their land was confiscated even if they were not categorized as absentees and were sheltering in their own village. Palestinian farmers leasing the village land from the new Israeli government had to commit not to employ refugees whose origins were from those villages, in order to protect the former against what the government called ''discomforts''.Even people who had left their homes to hide in the next village, or even the next hill, as in the case of ’Ayn Hud, could not get their property back and had to look at it from the next hilltop (until this very day).

According to those laws the land of Lubya was registered as state land, and divided between the neighboring Jewish settlements. The internal refugees from Lubya stayed in Dayr Hana, Nazareth and other towns. The physical destruction and the formal, legal, and human absences together with the silenced and denied memory turned Lubya into a ''site of void''.

----------------------------

- Groag, Shmuel (2006). On Conservation and Memory: Lubya – Palestinian Heritage Site in Israel, MSc Dissertation, Dept. of Sociology, London School of Economics and Political Science

- Khalidi, Walid (1992). All That Remains. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies

- Issa, Mahmoud (2003). Resisting Oblivion: Historiography of the Destroyed Palestinian Village of Lubya. Refuge, 21(2), pp. 14-22.

- Morris, Benny (1987). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947-1949. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Nashashibi, Rami (1996). Lubya. Center for Research and Documentation of Palestinian Society, Birzeit University

Videos

Refugee from Lubya

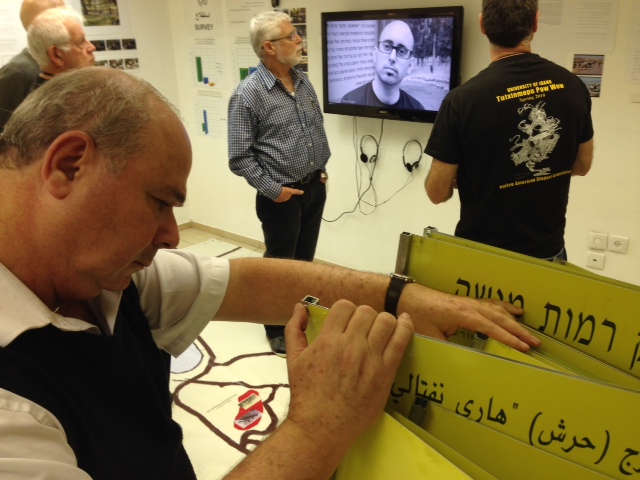

footages from Lubya tour | May, 2015

---------

Lubya is a destroyed Palestinian village located in the north of Palestine. 2730 people lived in the village until 1948

The erased village is now covered by the pine trees of Lavie Forest, part of which is called South Africa Forest. The village’s extensive lands are now occupied by Kibbutz Lavie, the Giv’at Avni communal settlement, part of Tiberias’ Neighborhood D, the Golani Industrial Park and Commemoration Site, and the Jordan River Village Camp for chronically ill children.

After 1948, the majority of Lubya’s refugees lived in refugee camps in Lebanon, Syria and Jordan. A few remained in Israel as internally displaced persons.

Some of Lubya’s refugees were killed in Syrian Civil War, mainly in al-Yarmouk Refugee Camp.

Full tour

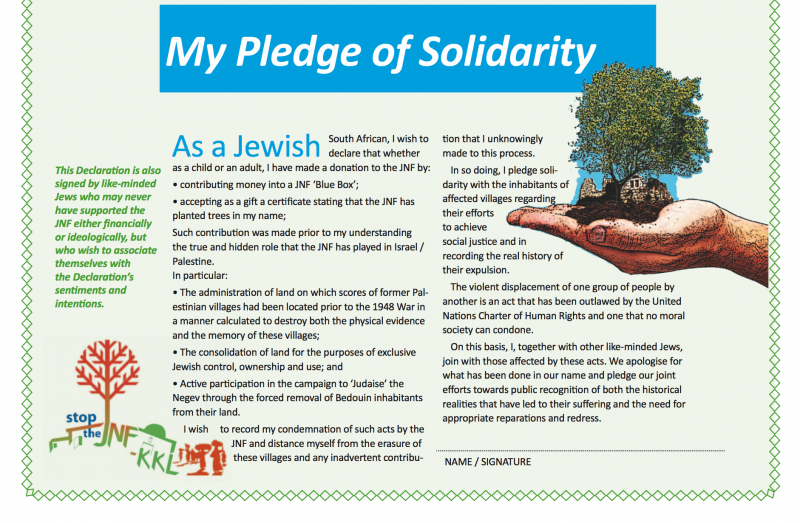

An Initiative of StopTheJNF South Africa

Refugee from Lubya - Tiberias District

A report on two activities at Palestinian Destroyed Villages

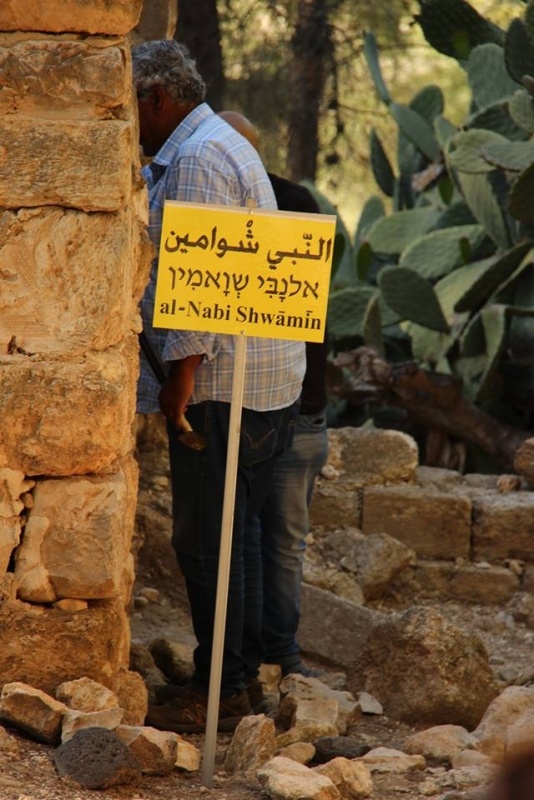

A South African Jewish group of "Stop The JNF South Africa" organized on the 1st of May 2015, in cooperation with Zochrot, a public ceremony to apologize for using their funds by the JNF in building up the "South Africa Forest" on the Palestinian lands of the destroyed village Lubya.

Unfolding as a personal meditation from the Jewish Diaspora, The Village Under The Forest explores the hidden remains of the destroyed Palestinian village of Lubya, which lies under a purposefully cultivated forest plantation called South Africa Forest.

Using the forest and the village ruins as metaphors, the documentary explores themes related to the erasure and persistence of memory and dares to imagine a future in which dignity, acknowledgement and co-habitation become shared possibilities in Israel/Palestine.