Info

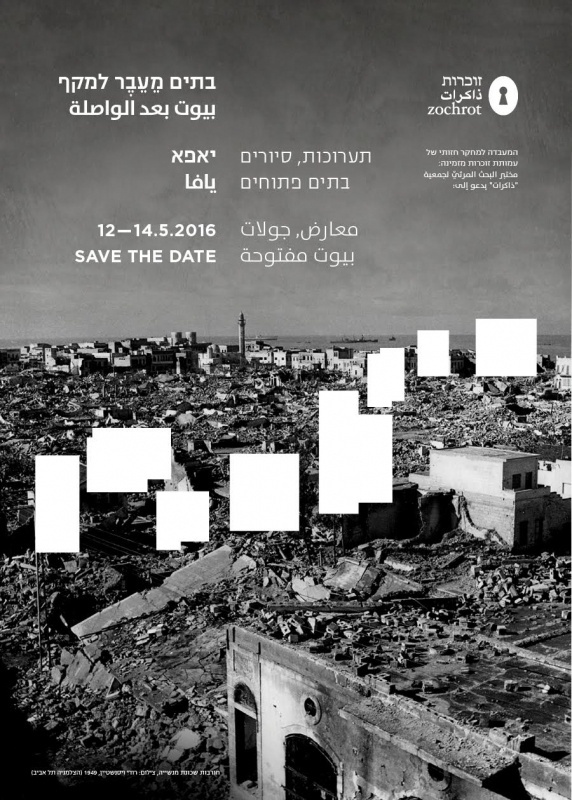

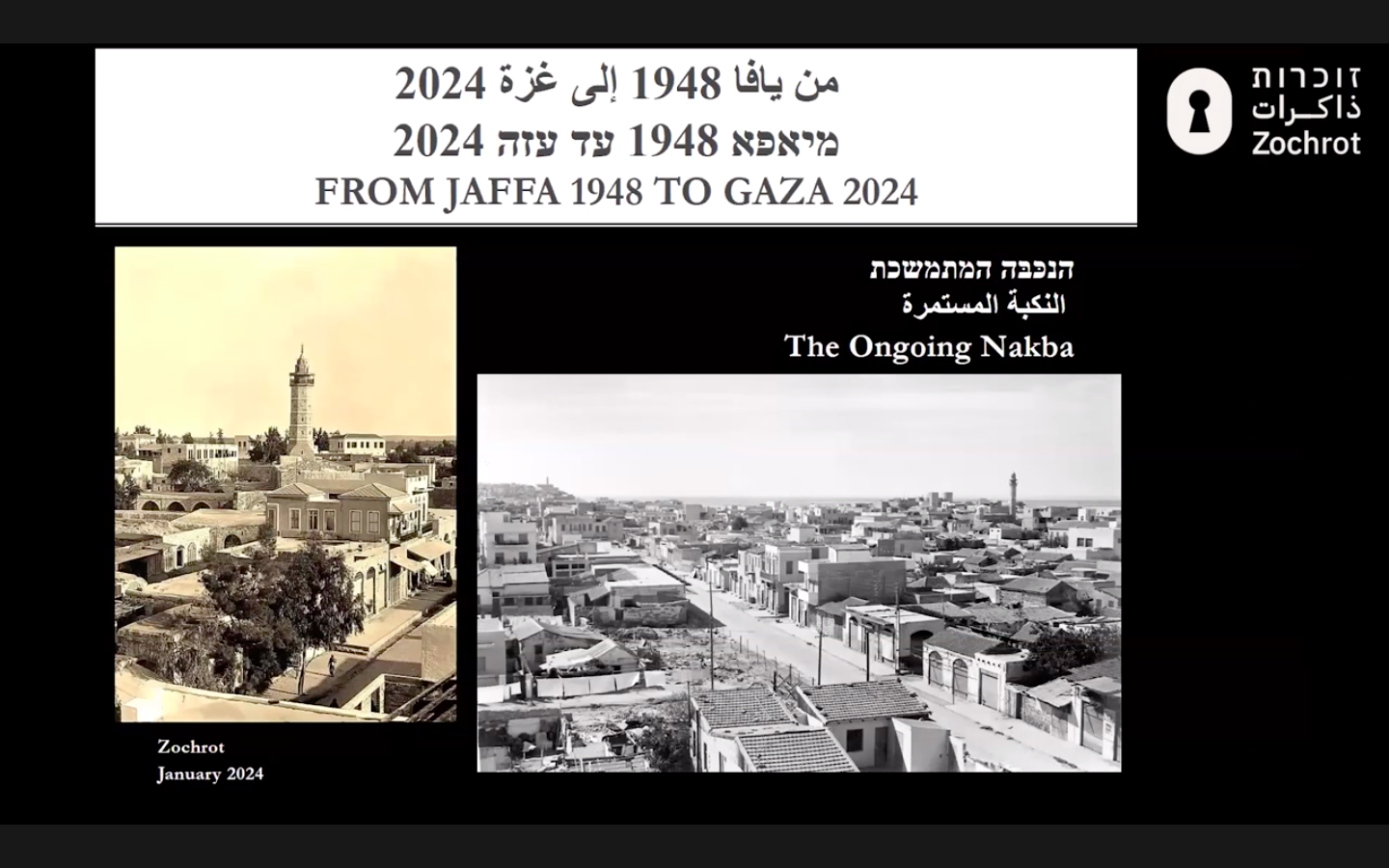

District: Jaffa

Population 1948: 76920

Occupation date: 13/05/1948

Occupying unit: Irgun (Etzel) & Hagana units

Jewish settlements on village/town land before 1948: Tel Aviv

Jewish settlements on village/town land after 1948: Bat-Yam Neighborhoods (Amidar), Ramat Yosef, Ramat Hanasi, Holon Neighborhoods (Tel Giborim), Neot Rachel, Jessy Cohen

Background:

Jaffa

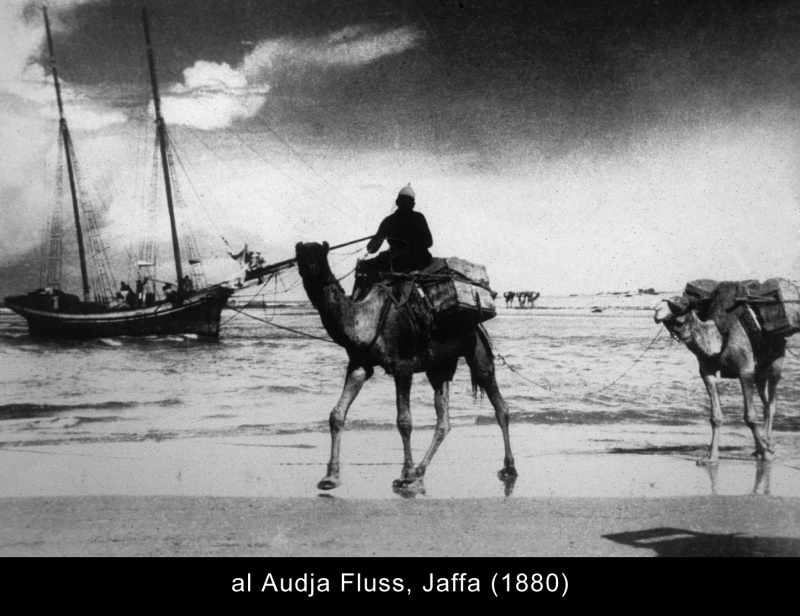

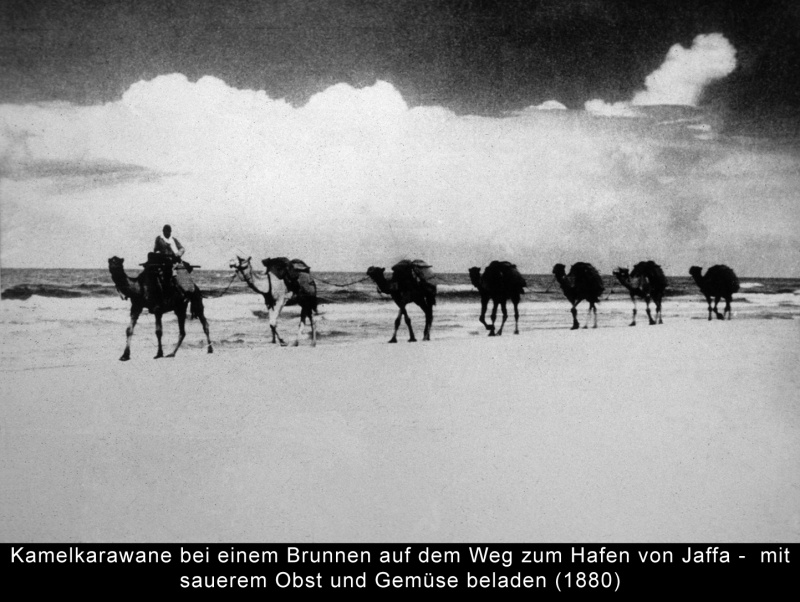

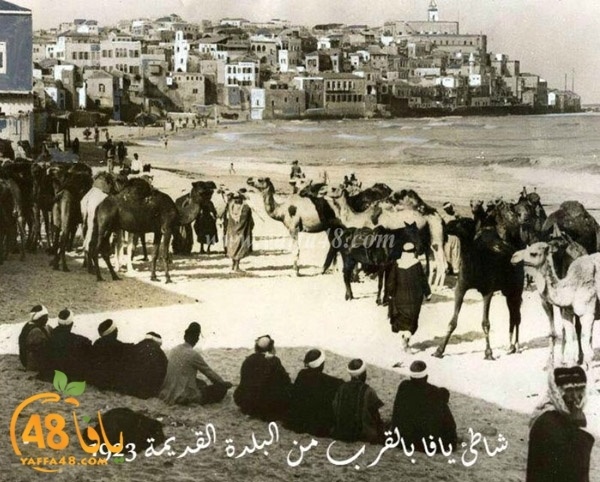

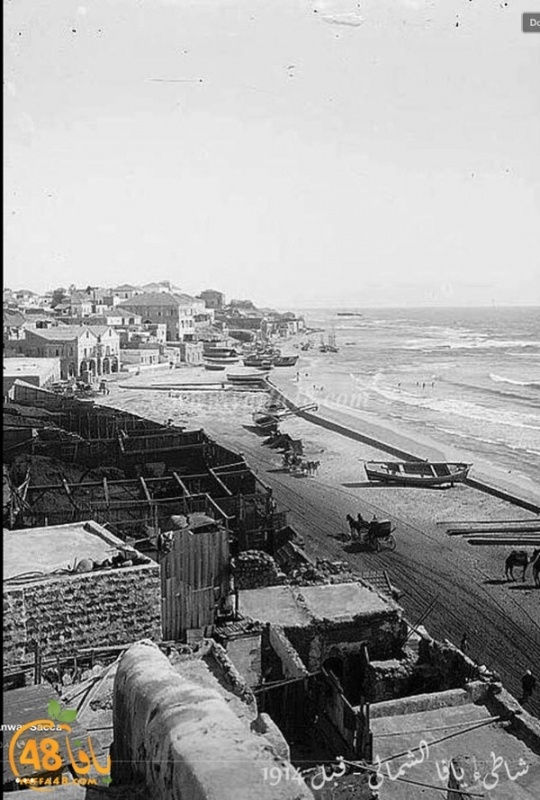

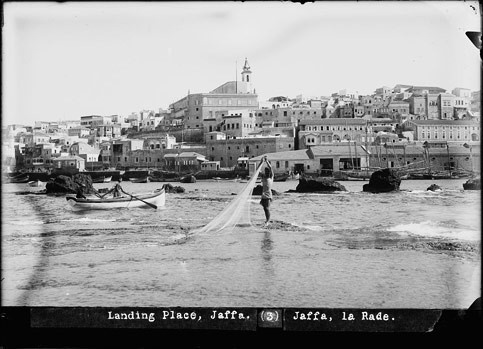

The city of Jaffa is one of civilization’s oldest meeting points, stretching back from the Chalcolithic period, around 4000 BC (Kaplan, 1972, p. 80). Jaffa’s landscape was ideally suited to serve as a settlement as well as military outpost for conquering and defending empires and nations, and provided a strategic position for security, trade, and agriculture. The city’s harbor is protected by a 130-foot rocky hill that slopes downwards to the sea, projecting into a cape, which offers a landmark visible from afar (Tolkowsky, 1924). Behind the hill to the east lies a stretch of fertile soil, which has made Jaffa to world famous for its orangs.

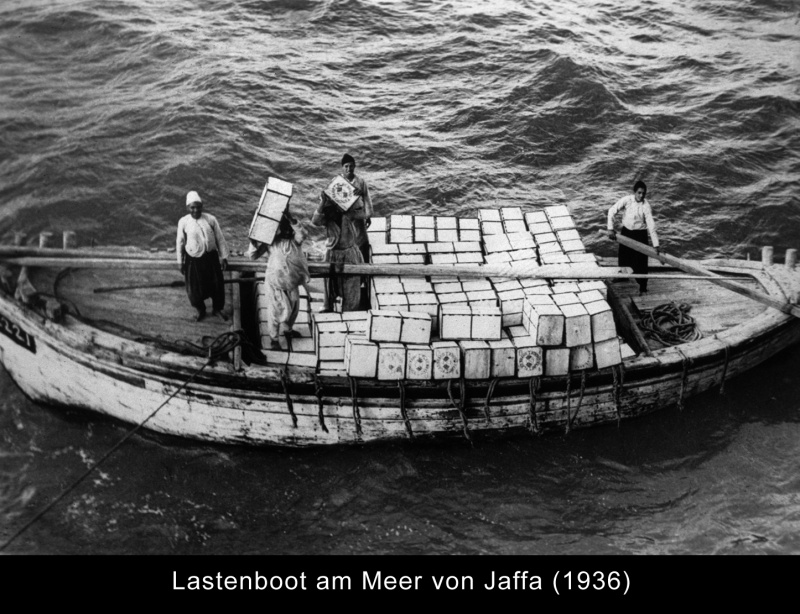

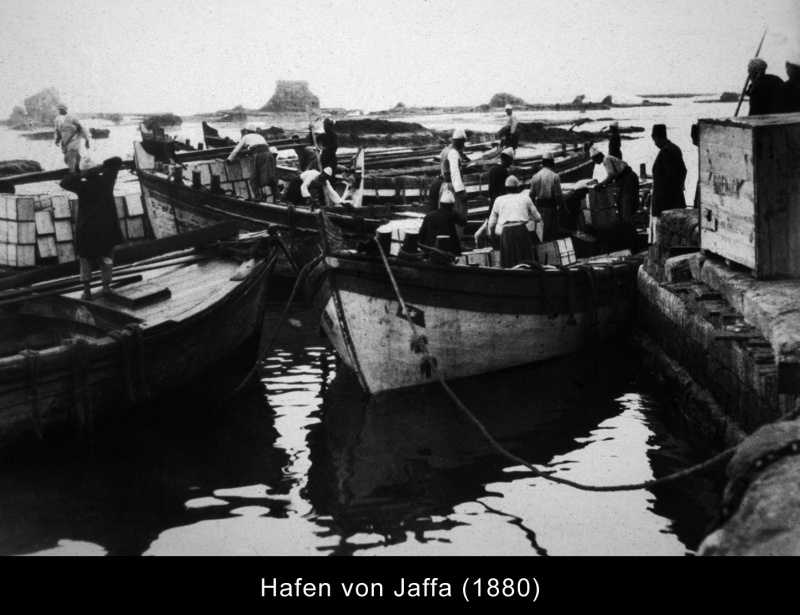

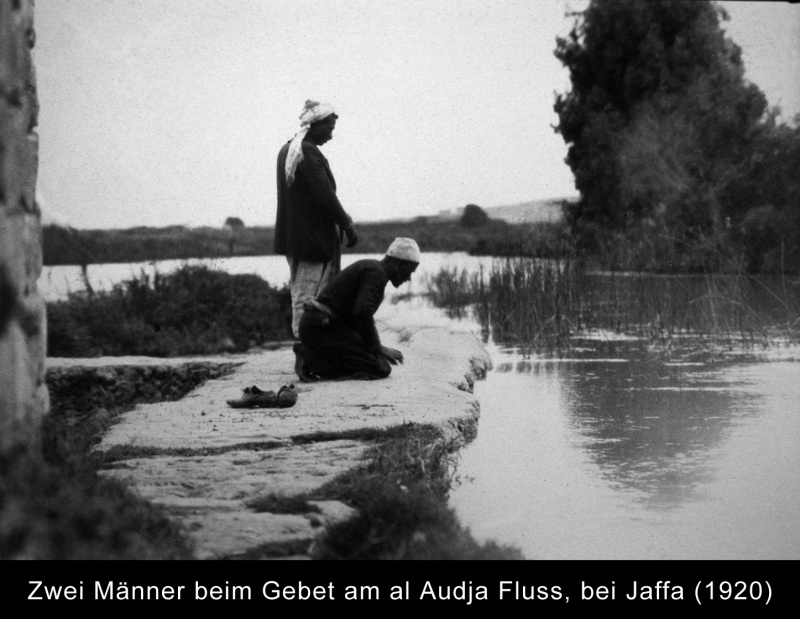

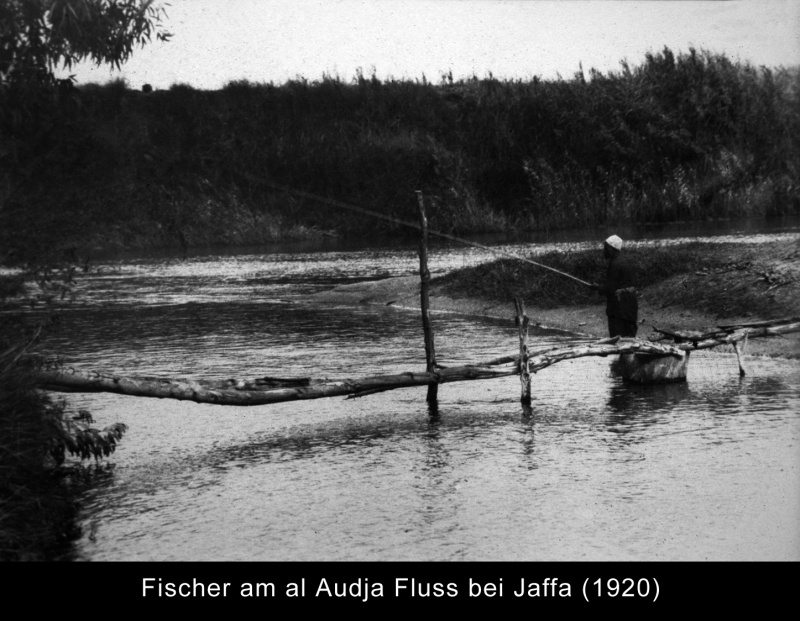

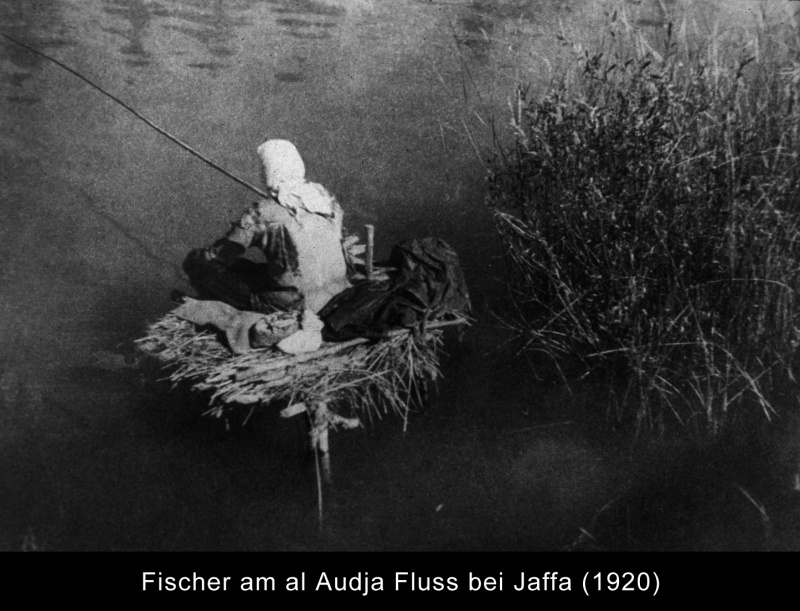

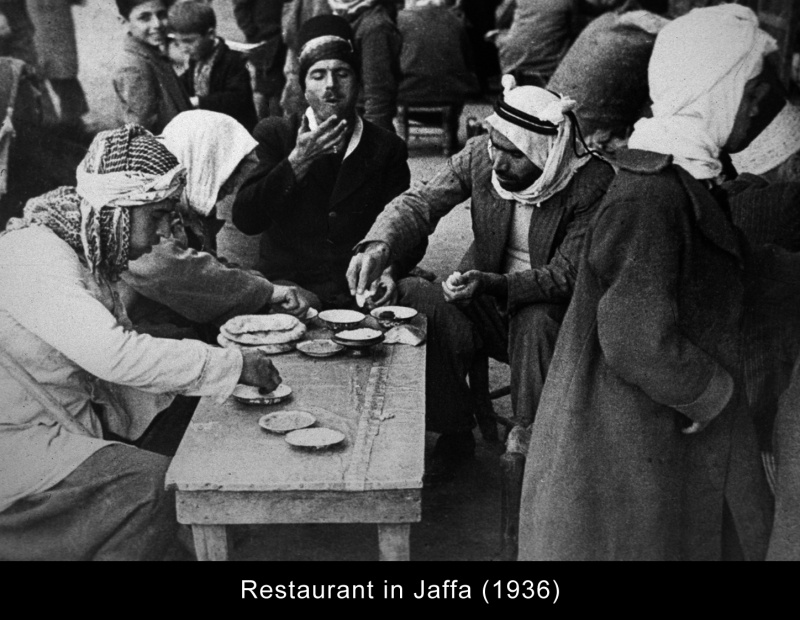

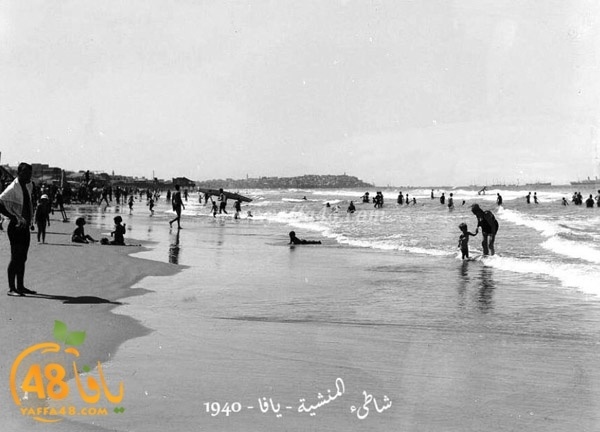

Throughout Jaffa’s early expansion, the majority of its inhabitants were employed in fishing and growing fruits, vegetables and various grains. Early industries developed, mainly olive oil, soap and wine, and the development of shipping led to expanding trade routes connecting Jaffa with Egypt, Cyprus, as well as the coasts of Asia Minor and the Aegean isles (Tolkowsky, 1924).

Empires, Conquerors, and Nations

In 1472 BC, Pharaoh Thutmose III of the Eighteenth Dynasty occupied Jaffa in a highly deceptive campaign involving a small fleet of 400 men. They overtook the city in a surprise attack by smuggling 200 soldiers into the city hidden in giant jars (Tolkowsky, 1924). This historical era can still be witnessed today through the restoration of the ancient 13th-century Ramesside gateway, located in what is now the park area of the Old City.

Subsequent events can be traced in biblical references to the borders of the Israelite tribe of Dan, wherein Jaffa was included (Joshua 19: 40-48; Peilstocker & Burke, 2011). Jaffa continued to be a prized possession for all the empires and civilizations of the region. The precious port city was transferred from the Greeks, to the Romans, to the Byzantines, and various Moslem Arab dynasties wrestled with Jaffa for half a century only to be overcome by the Crusaders in 1099 AD (Tolkowsky, 1924).

Crusader Conquest and Ottoman Control

Jaffa proved to be a strategic city for the Christian armies on their way to the holy jewel of Jerusalem. Their leader, Godfrey of Bouillon, initially occupied Jaffa in 1099 and used the town’s strategic location as a rallying point and supply center for Crusader armies coming from across the Holy Catholic Empire (Asbridge, 2013). Jaffa’s significance was highlighted through the ongoing rivalry between Saladin and King Richard the Lionheart during the Third Crusade. The city was host to a final bloodbath that resulted in a peace treaty signed in 1192 between the two great adversaries.

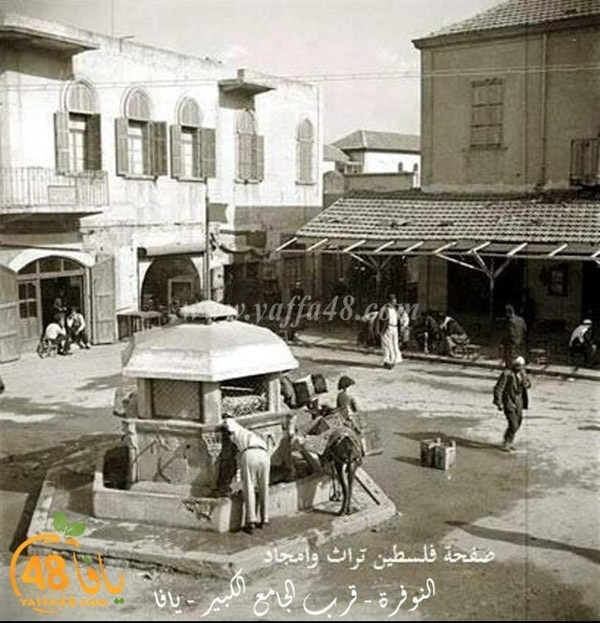

After the collapse of the Crusader Kingdoms, Jaffa lost much of its strategic importance. In 1517, the Ottoman Turks conquered the city together with the rest of Palestine, and remained their rulers for the next 400 years. In the 18th century, Jaffa began to undergo intensive development and expansion. The present-day stone wharf began to take shape in 1740, with the rapid expansion of homes, mosques, and gardens (Tolkowsky, 1924). This period saw the city grow into a bustling center of commerce, reaching a population of 5,000-6,000 (Peilstocker & Burke, 2011).

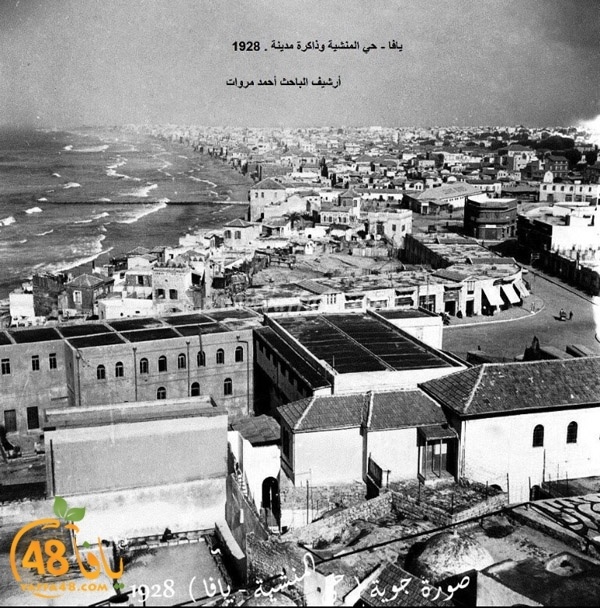

The nineteenth century solidified Jaffa’s transformation from primarily a strategic military outpost to a thriving urban settlement. This expansion was assisted by the development of the first railway in Palestine, connecting Jaffa and Jerusalem in 1892 (Tolkowsky, 1924). Such modern developments further spiked population growth, bringing Jaffa’s population to 8,000 by 1876, including 1,800 Christians and 600 Jews. With the Great War quickly approaching, Jaffa continued to expand at an unprecedented rate, becoming the second largest city in Palestine with a population of up to 50,000 (30,000 Arab Muslims, 10,000 Christians, and 10,000 Jews) (Peilstocker & Burke, 2011).

British Mandate and 1948

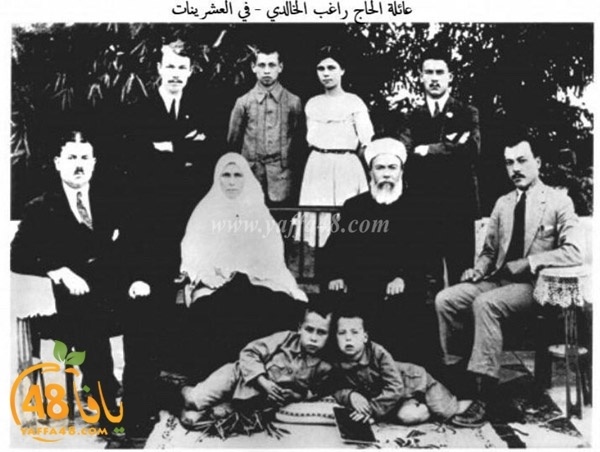

One of the arguments for the formation of a new emerging Arab identity can be traced back to the last decades of Sultan Abdul Hamid’s Ottoman Empire. Throughout the 1870s, a growing number of Arab intellectuals began to challenge Ottoman rule in Syria, Lebanon and Palestine (Pappé, 2006). Ernest Dawn (1961) accounts for 22 Palestinians in the 126-member Arab nationalist societies in 1914. The end of the war involved the transfer of Palestine from Ottoman to British control, paving the way for a new image of Jaffa and Palestine altogether. The British Mandate ushered in another series of changes. In 1921, the Jewish neighborhood of Tel Aviv became a “township”, and by 1934, it received “municipal corporation” status, distinguishing it as a completely separate legal entity from Jaffa (Karlinsky, in print).

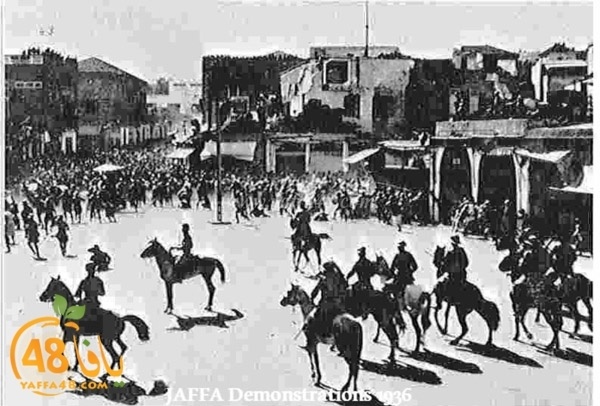

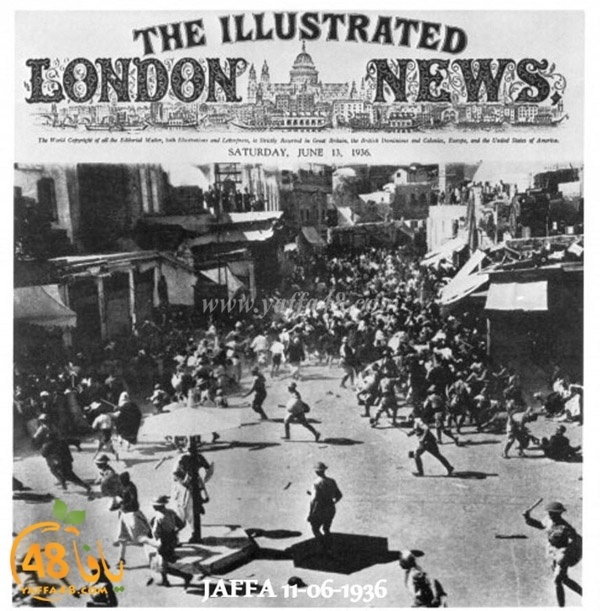

By the late 1940s, Jaffa was home to upwards of 70,000 Palestinian Arabs and 30,000 Jews (LeVine, 2007). According to the UN Partition Plan, it was to be an enclave of the Arab State inside the Jewish State. Within hours of the UN vote in November 1947, fighting broke out on the border of the Arab Manshiyya neighborhood and Tel Aviv, lasting several days (Aleksandrowicz, 2016). Sniper fire into homes, cafes, and onto the streets escalated into an attack by Arab fighters on the Hatikvah neighborhood of Tel Aviv, resulting in 60 Arabs and two Jews killed.

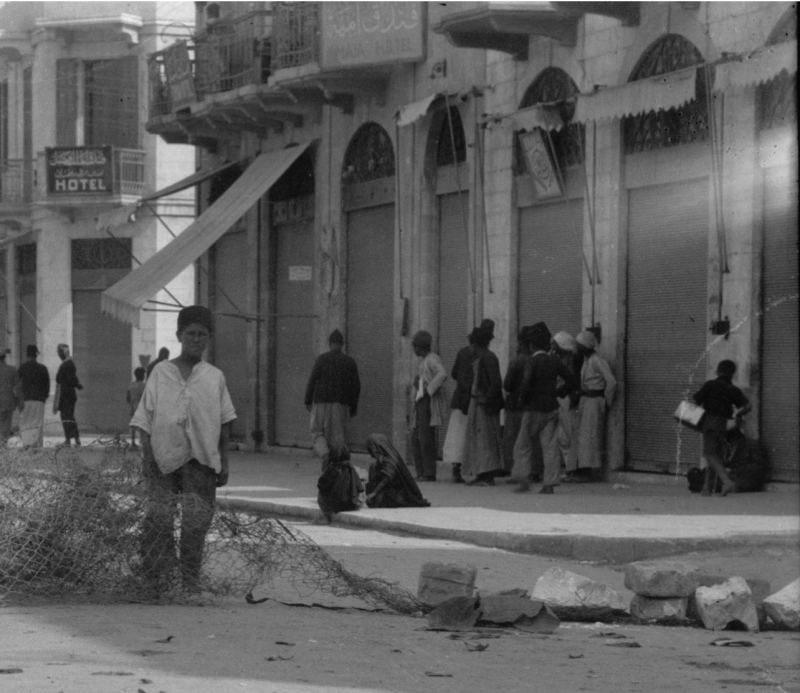

Thus began the Nakba. The violence led to an exodus of the Palestinian middle class from Jaffa, followed by the fleeing of the working class as shops and businesses closed and unemployment, poverty, and food shortages took over. Jewish businessmen also fired their Palestinian employees. Residents of Manshiyya in the north and Abu Kabir in the south were seen fleeing the city, pushing handcarts full of their belongings, according to reports from the intelligence service of the Haganah Jewish militia (LeBor, 2017, pp. 105-109).

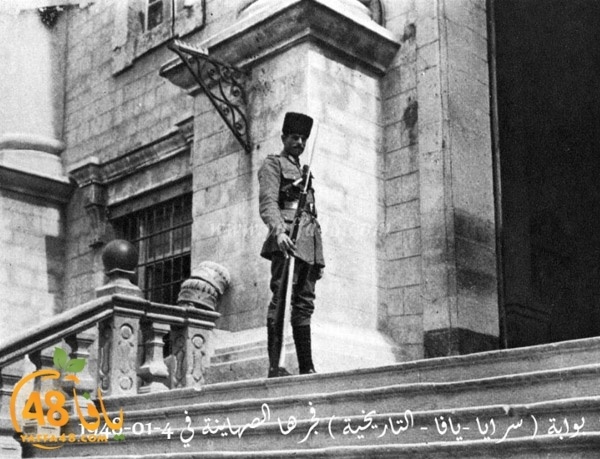

Jewish and Arab orange grove owners signed a non-aggression pact soon after, in the winter of 1948, in order to preserve the plantations around the city for harvest. On January 4, a truck loaded with oranges exploded next to the New Seraya, a government building housing Jaffa’s municipal office, welfare workers, and a kitchen for needy children in the Clock Tower Square; 26 were killed and hundreds injured, mostly civilians and children. The bomb missed its target as the Arab Higher Committee had already moved to the Ajami neighborhood to organize Jaffa’s resistance. According to current Jaffa resident Ismail Abu-Shehade who was working at a garage nearby when he heard the explosion, “They claimed that the Seraya was a center for terrorists, but it was nothing but an orphanage. Lots of children were killed” (LeBor, 2017, p. 108). The bombing, by extremist Jewish militants, terrorized Jaffa. Municipal services nearly ceased, and the middle-class exodus accelerated further. The Jewish Irgun militia (Etzel) knew when Jaffa residents would meet in cafes to hear the daily news broadcasts and would roll in barrels filled with explosives (LeBor, 2017, p. 111). In January, an Arab informant told Elias Sasson, head of the Jewish Agency’s Arab Affairs Department: “whoever could leave has left, there is fear everywhere, and there is no safety” (LeBor, 2017, p. 105).

By early April 1948, it was estimated that more than 30,000 of the 73,000 prewar Arab residents of Jaffa had left the city (Golan, 2009). The port was overwhelmed with thousands of refugees cramming into small boats to find little space on larger vessels anchored out to sea. As the larger ships set off, they became targets of shells as they passed Tel Aviv, according to refugee Mustafa Hammami. Jaffa fisherman Abu-Shehade recalls: “People then started to leave by ships and trains. All the routes to the Arab countries were open, and people could leave for free... After a week there was nothing left but cats and dogs. We few families who stayed, went to live in the orange groves” (LeBor, 2017, p. 117).

On April 25, three weeks before the end of the British Mandate, the Irgun attacked Manshiyya for six days with small arms and mortars. Most wartime destruction was limited to the strip between Arab and Jewish lines on the northern and eastern borders of Manshiya, without air bombing or heavy artillery. However, Jaffa’s resulting isolation, “dilapidated leadership, and hopeless situation” forced it to surrender (Aleksandrowicz, 2016, p. 185) Despite last-minute British efforts to persuade the Jewish leadership not to take over the Arab city, on May 13, 24 hours before the declaration of Israel’s independence, Jaffa surrendered and was placed under Israeli military rule (Golan, 2009).

Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion declared in a cabinet meeting in June that “We must settle Jaffa, Jaffa will become a Jewish city” as Jewish troops began to loot property left behind in vacant Palestinian homes (LeBor, 2017). Israeli authorities estimated that the Nakba left 2,800 buildings available for accommodation in Jaffa, comprising 16,000 rooms (Golan, 2009). In July, the newly formed Israeli government created a Transfer Committee to prevent the return of the refugees and to settle new Jewish immigrants, including Holocaust refugees, in the now vacant homes.

About three thousand of Jaffa’s original Arab inhabitants remained at the time of surrender, while two thousand more were subsequently allowed to return for family reunification (LeBor, 2017). The results of the Nakba were clear: almost all remaining Palestinians were forced into a fenced area in the Ajami quarter – called the Ghetto by both Arabs and Jews. By early 1949, there were over forty thousand Jews living in Jaffa, at least thirty thousand of whom were new immigrants (Golan, 2009).

Post 1948

After a series of Emergency Regulations passed from 1948-1950 to deal with the property and land left behind by Palestinian refugees, the Absentees Property Law was passed in March 1950 to consolidate and formalize the state’s confiscation of abandoned Palestinian homes (Aleksandrowicz, 2016). On April 24, the Israeli government announced the official unification of the Tel Aviv and Jaffa municipalities (Golan, 2009).

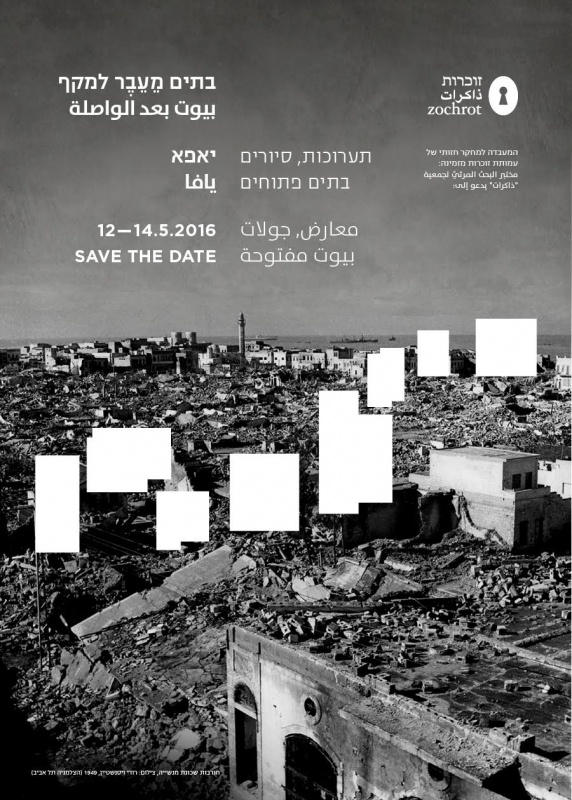

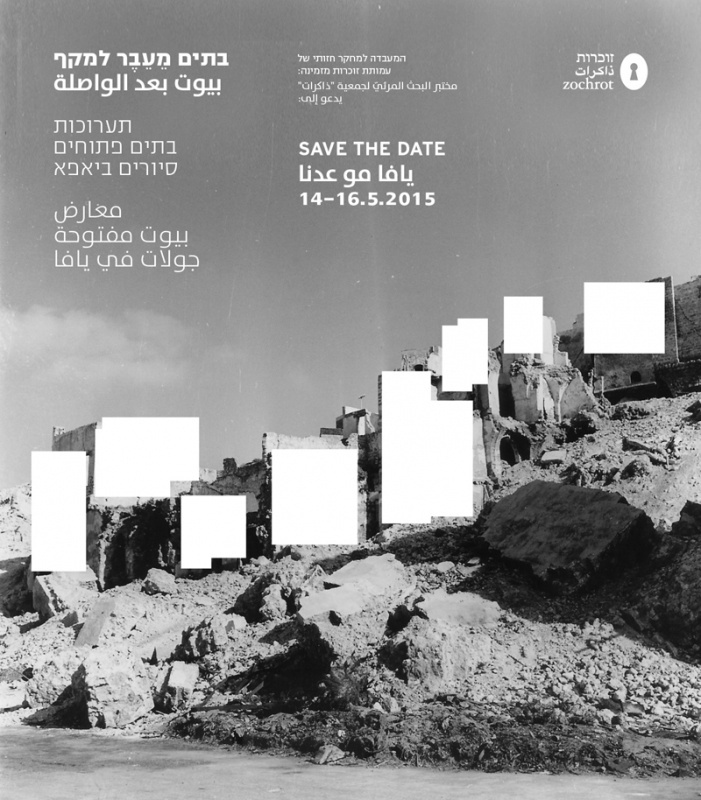

The widespread scheme of urban planning during the state’s first three decades led to large-scale physical destruction and exclusion of Palestinian residents (Meishar, 2017). The first master plans for West Jaffa compiled in the 1950s and 60s called for an almost total demolition of the existing Palestinian built area, which was replaced with modern housing projects, especially in the neglected Manshiya and Abu Kabir neighborhoods (Meishar, 2017; Golan, 2009). Over 16,000 housing units were constructed in the Tel Aviv-Jaffa municipal area during the 1950s and early 60s, including 3,300 on open lands of Jaffa to provide housing for residents of temporary immigrant camps, working-class and lower-middle-class people, and demobilized soldiers (Golan, 2009). Israeli authorities also renovated and divided remaining Palestinian homes in order to increase the number of residential units (Meishar, 2017).

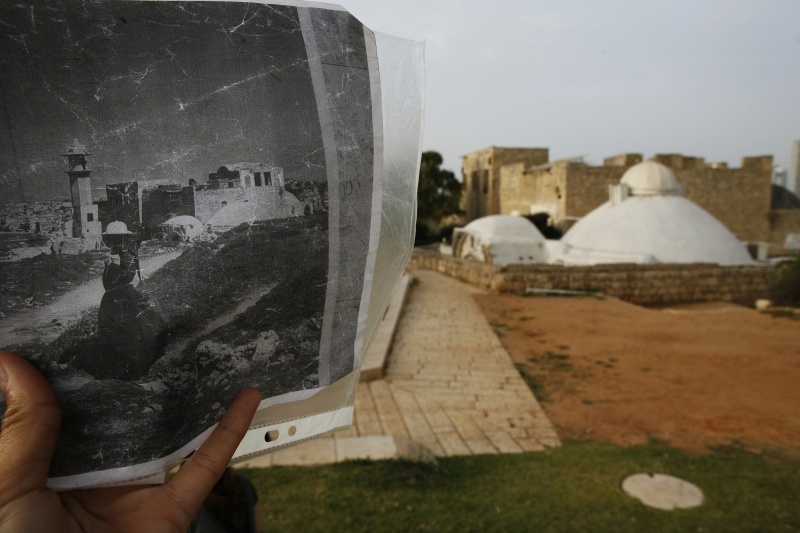

Originally slated for demolition, the Old City of Jaffa deteriorated in the 1950s into an area of crime and prostitution. In 1954, it was marked for preservation as a historical and archeological national park and an artists’ quarter. In the early 1960s, the remaining Palestinian residents as well as Jewish squatters were evacuated and preservation began on the historical precolonial core area, converting it into a tourist attraction. Former residences were mainly leased for restaurants and artists’ studios. The Jewish neighborhood Kiryat Shalom was built on former Arab citrus groves in the eastern part of Jaffa. Trees were planted to develop a park and some of the remaining buildings housed the Tel Aviv Zoological Institute that later became a part of Tel Aviv University (Golan, 2009).

During the 1970s and 80s, Jewish residents gradually moved out of Jaffa’s western neighborhoods to new neighboring housing projects. Arab residents remained and continued to grow in numbers, underserved by the municipality for another three decades. Since the Israeli urban master plan restricted any extension of existing buildings for these residents, they expanded their homes without legal permits. Many of these extensions were then destroyed and added to the waste mounds of Jaffa’s ruins piled on the city’s shore along with additional construction waste from the entire Tel Aviv area. This gradually resulted in a fifteen-meter-high construction-waste hill that expanded deep into the Mediterranean (“Garbage Mountain”). It was covered over with the Jaffa Slope Park in 2010, mirroring the coastal Charles Clore Park that hides the ruined neighborhood of Manshiya (Meishar, 2017).

In the late 1980s and 90s, Jaffa developed as both a site for tourism and as a new neighborhood for the growing Jewish elite of “global Tel Aviv” (LeVine, 2007). The Judaization-gentrification of Jaffa continued apace as a result of larger economic and housing market factors in the greater metropolitan area. When Palestinian community leaders complained in the early 2000s that most young Palestinian couples could not afford to live in Jaffa, officials responded by explaining that “the market is the market,” and that “selling some apartments more cheaply would hurt profits” (LeVine, 2007, p. 192). Since then, real-estate values have more than doubled (Ami Asher, personal communication, October 2018).

Discrimination also continues to play a central role in the social life of Jaffa’s Palestinian residents. It is a major factor in differences in wages, access to jobs, and educational levels between Palestinians and Jews. The situation has only been exacerbated by the large increase in Jaffa’s Palestinian population and the influx of Russian immigrants, who took away jobs and housing from the local residents after 1989. In fact, living conditions and opportunities in Jaffa drastically deteriorated in the 90s, to the point where Palestinian Jaffa has become a significantly depressed and disadvantaged community. Contemporary Jaffans protest how their city has been reduced to little more than a footnote on the name of Tel Aviv since the 1948 Nakba (LeVine, 2007).

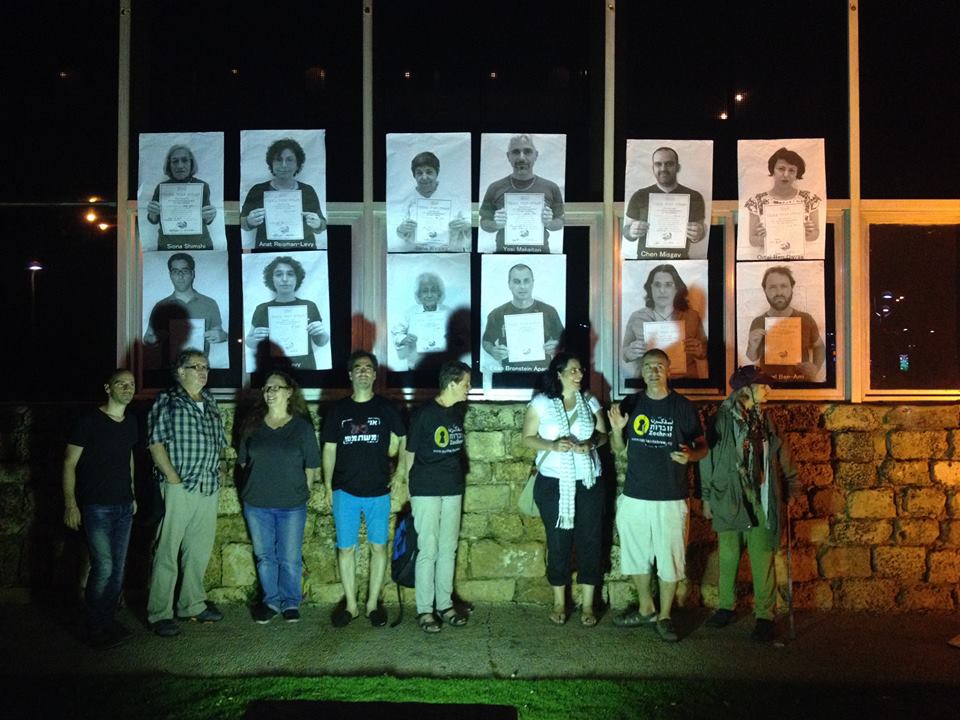

This essay was written by Zochrot in 2018. Special thanks to Elliot Beck and Matt Letkeman for their research and writing this article about Yaffa.

--------------------------------------

References

Aleksandrowicz, Or. "The Camouflage of War: Planned Destruction in Jaffa and Tel Aviv, 1948." Planning Perspectives, vol. 32, no. 2, 2016, pp. 175-98.

Dawn, Ernest C. "From Ottomanism to Arabism: The Origin of an Ideology." The Review of Politics, vol. 23, no. 3, 1961.

Golan, Arnon. “War and Postwar Transformation of Urban Areas: The 1948 War and the Incorporation of Jaffa into Tel Aviv.” Journal of Urban History, vol. 35, no. 7, 2009, pp. 1020-1036.

Kaplan J. “The Archaeology and History of Tel Aviv-Jaffa.” The Biblical Archaeologist. Vol. 35, No. 3 (Sep., 1972), pp. 65-95

Karlinsky, Nahum. "The Limits of Separation: Jaffa and Tel Aviv before 1948: The Underground Story." Tel Aviv at 100: Myths, Memories and Realities. In print.

LeBor, Adam. City of Oranges: Arabs and Jews in Jaffa. W. W. Norton & Company, 2006.

LeVine, Mark. “Globalization, Architecture, and Town Planning in a Colonial City: The Case of Jaffa and Tel Aviv.” Journal of World History, vol. 18, no. 2, June 2007, pp. 171–198.

Meishar, Naama. “Up/Rooting: Breaching Landscape Architecture in the Jewish-Arab City.” AJS Review, vol. 41, no. 1, April 2017, pp. 89–109

Pappé, Ilan. History of Modern Palestine: One Land, Two Peoples. 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Peilstocker, Martin, and Aaron A. Burke. Historical and Archaeology of Jaffa. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, 2011.

Tolkowsky, S. The Gateway of Palestine: A History of Jaffa. 2nd ed., George Routledge & Sons, 1924.